Direct Answer

Inrush current is the maximum instantaneous surge of electrical current drawn by an electrical device when it is first turned on. This transient current spike can reach 2 to 30 times the normal steady-state operating current, depending on the type of equipment. The phenomenon typically lasts from a few milliseconds to several seconds and occurs primarily in inductive loads such as transformers, motors, and capacitive circuits. Understanding inrush current is critical for proper circuit breaker sizing, preventing nuisance tripping, and ensuring equipment longevity in industrial and commercial electrical systems.

Key Takeaways

- Inrush current is a momentary surge that occurs during equipment startup, reaching 2-30× normal operating current

- Primary causes include magnetic core saturation in transformers, rotor standstill in motors, and capacitor charging in power supplies

- Circuit breakers must be properly sized to tolerate inrush without nuisance tripping while still providing overcurrent protection

- Typical inrush magnitudes: Transformers (8-15× rated current), motors (5-8× full load current), LED drivers (10-20× steady state)

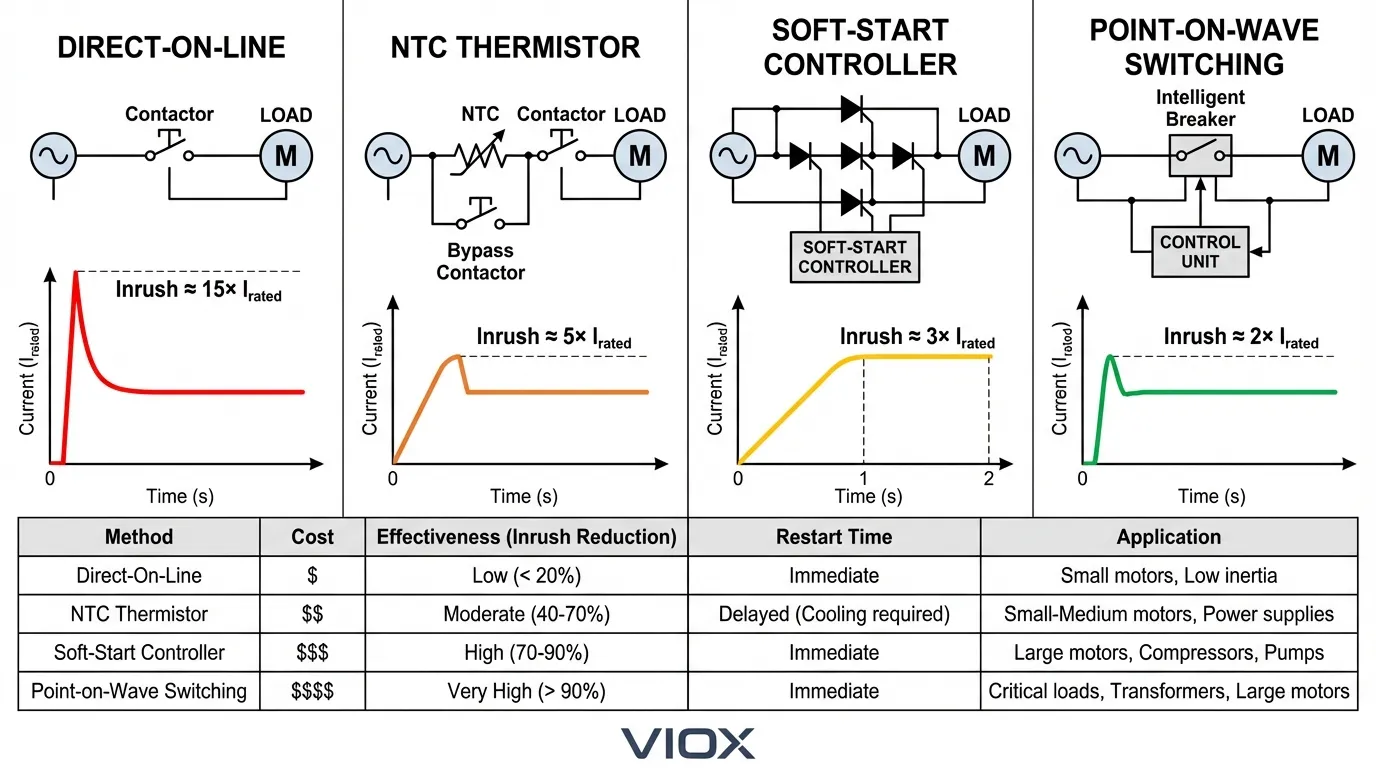

- Mitigation methods include NTC thermistors, soft-start circuits, pre-insertion resistors, and point-on-wave switching

- Calculation requires understanding of equipment type, residual flux, switching angle, and system impedance

What Is Inrush Current?

Inrush current, also known as input surge current or switch-on surge, represents the peak instantaneous current that flows into an electrical device at the moment of energization. Unlike steady-state operating current, which remains relatively constant during normal operation, inrush current is a transient phenomenon characterized by its extremely high magnitude and short duration.

This current surge is not a fault condition but rather a natural consequence of the physical principles governing electromagnetic devices. When power is first applied, inductive components must establish their magnetic fields, capacitors must charge to operating voltage, and resistive heating elements start from cold resistance values—all of which temporarily demand far more current than normal operation requires.

The severity and duration of inrush current vary significantly based on equipment type, system characteristics, and the precise moment in the AC waveform when switching occurs. For electrical engineers and facility managers, understanding these variables is essential for designing reliable protection schemes and preventing operational disruptions.

Root Causes of Inrush Current

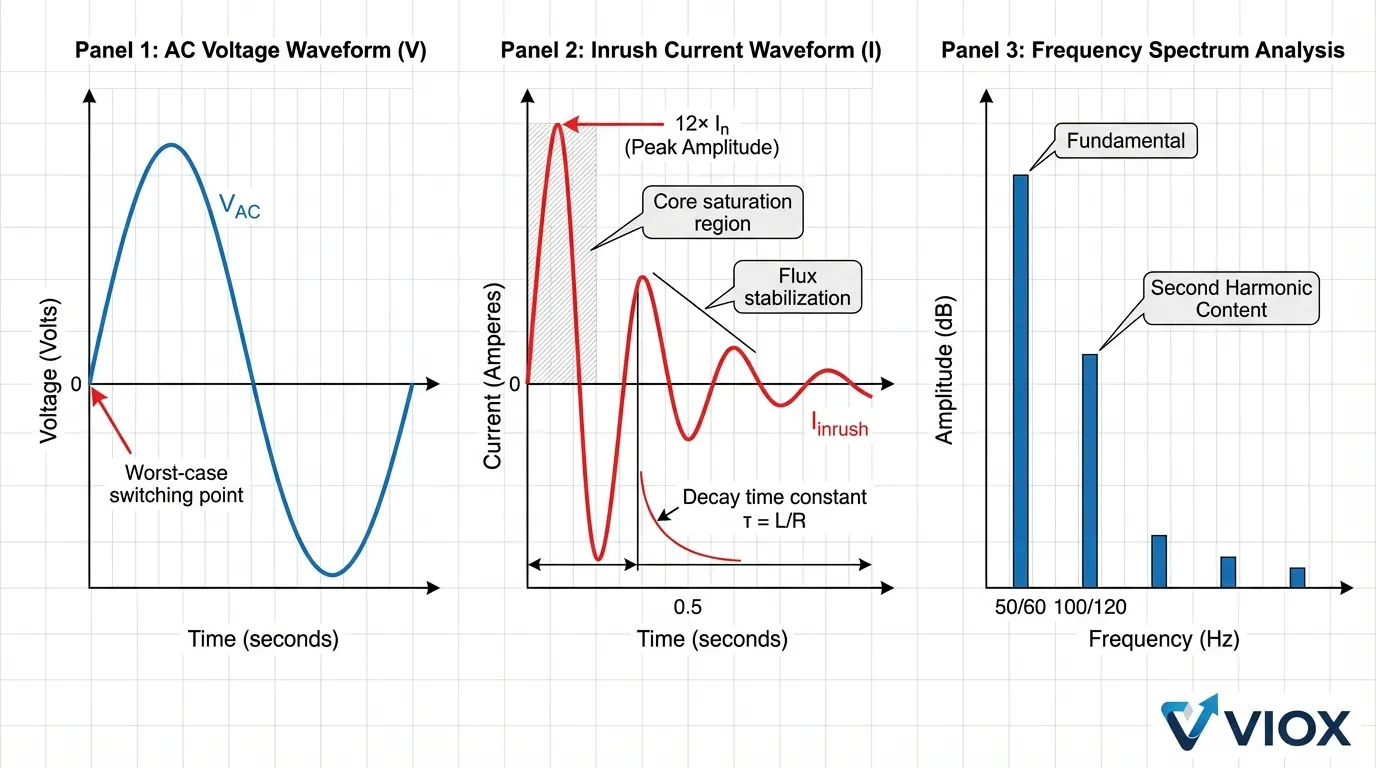

Transformer Inrush: Magnetic Core Saturation

Transformers experience the most dramatic inrush currents in electrical systems. When a transformer is first energized, the magnetic flux in its core must build from zero (or from residual magnetism) to its operating level. If energization occurs at an unfavorable point in the voltage waveform—particularly at voltage zero-crossing—the required flux can exceed the core’s saturation point.

Once the core saturates, its magnetic permeability drops drastically, causing the magnetizing impedance to collapse. With impedance reduced to essentially the winding resistance, current surges to levels 8-15 times the transformer’s rated current. This phenomenon is further amplified by residual flux remaining in the core from previous operation. The polarity and magnitude of residual flux can either add to or subtract from the required flux, making inrush current somewhat unpredictable.

The inrush current in transformers exhibits a characteristic asymmetric waveform rich in second-harmonic content, which distinguishes it from short-circuit faults. This transient typically decays within 0.1 to 1 second as the magnetic flux stabilizes and core saturation diminishes.

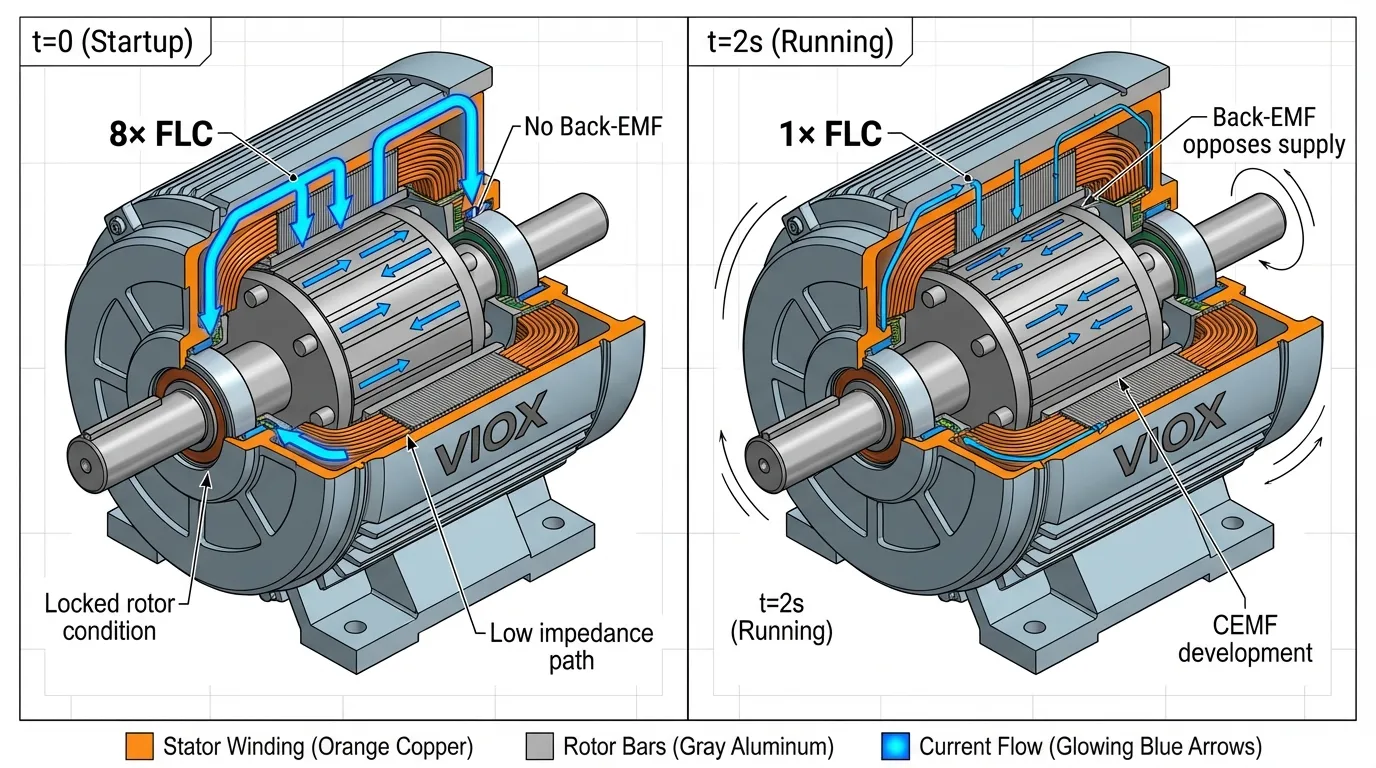

Motor Starting Current

Electric motors draw high inrush current because the rotor is stationary at startup. Without rotational motion, there is no counter-electromotive force (CEMF or back-EMF) to oppose the applied voltage. The starting current is limited only by the winding impedance, which is relatively low.

For induction motors, locked-rotor current typically ranges from 5 to 8 times the full-load current, though some designs can reach 10 times. The exact magnitude depends on motor design, with high-efficiency motors generally exhibiting higher inrush due to lower winding resistance. As the rotor accelerates, back-EMF develops proportionally to speed, progressively reducing current draw until steady-state operation is reached.

Motor starters and contactors must be specifically rated to handle this repetitive inrush without contact welding or excessive wear.

Capacitive Load Charging

Switching power supplies, variable frequency drives, and other electronic equipment with large input capacitors create severe inrush currents during turn-on. An uncharged capacitor initially appears as a short circuit, drawing maximum current limited only by source impedance and circuit resistance.

The charging current follows an exponential decay curve, with the time constant determined by the circuit’s RC characteristics. Peak inrush can easily reach 20-30 times the steady-state current in poorly designed circuits. Modern power electronics increasingly incorporate active or passive inrush limiting to protect both the equipment and upstream distribution systems.

Incandescent and Heating Element Cold Resistance

Tungsten-filament incandescent lamps and resistive heating elements exhibit substantially lower resistance when cold compared to their hot operating state. Tungsten’s resistance increases by approximately 10-15 times as it heats from room temperature to operating temperature (around 2,800°C for incandescent bulbs).

This cold-resistance effect means that a 100W incandescent lamp can draw 10-15 times its rated current for the first few milliseconds until the filament heats. While individual lamps present minimal issues, large banks of incandescent lighting or heating elements can create significant inrush that must be considered in circuit breaker selection.

Effects of Inrush Current on Electrical Systems

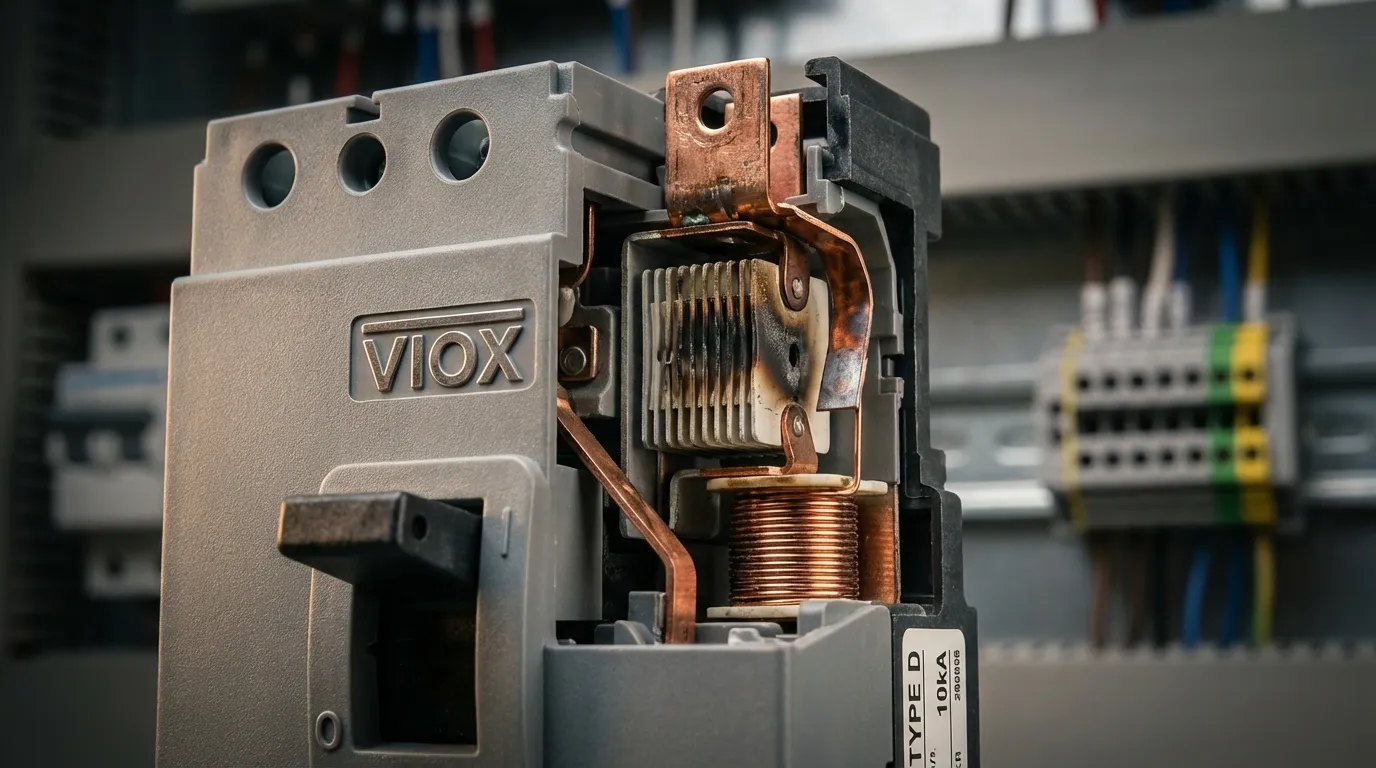

Circuit Breaker Nuisance Tripping

The most common operational problem caused by inrush current is nuisance tripping of circuit breakers and fuses. Protective devices must discriminate between harmful fault currents and benign inrush transients—a challenging engineering task.

Thermal-magnetic circuit breakers use a time-current characteristic that tolerates brief overcurrents while responding quickly to sustained faults. However, if inrush magnitude or duration exceeds the breaker’s tolerance envelope, it will trip unnecessarily. This is particularly problematic with MCBs and MCCBs that must protect both transformers and downstream loads.

The instantaneous trip element in circuit breakers typically sets between 5-15 times the rated current, depending on the trip curve (B, C, or D curve for MCBs). Transformer inrush can easily exceed these thresholds, necessitating careful coordination during system design. Understanding trip curves is essential for proper protection coordination.

Voltage Sag and Power Quality Issues

High inrush currents cause momentary voltage drops throughout the electrical distribution system. The voltage sag magnitude depends on the source impedance and the inrush current magnitude, following Ohm’s law: ΔV = I_inrush × Z_source.

In systems with high impedance or limited capacity, inrush from large loads can cause voltage dips of 10-20% or more. These sags affect other connected equipment, potentially causing:

- Computer and PLC resets

- Lighting flicker

- Motor speed variations

- Sensitive electronic equipment malfunction

- Voltage monitoring relay activation

Industrial facilities with multiple large motors or transformers must carefully sequence startup to prevent cumulative voltage depression that could destabilize the entire system.

Mechanical and Thermal Stress on Equipment

Repeated inrush events subject electrical equipment to significant mechanical and thermal stress. The electromagnetic forces generated by high currents are proportional to the square of the current (F ∝ I²), meaning a 10× inrush creates 100× the normal mechanical force.

In transformers, these forces stress winding supports and insulation, potentially causing cumulative damage over thousands of energization cycles. Contactors and motor starters experience contact erosion and welding risk during high inrush switching.

Thermal stress from I²t heating during inrush can degrade insulation and reduce equipment lifespan, even though the duration is brief. This is why thermal overload relays and electronic trip units must incorporate inrush immunity algorithms.

Harmonic Distortion and EMI

Transformer inrush current contains significant harmonic content, particularly second and third harmonics. This harmonic-rich waveform can:

- Interfere with power quality monitoring equipment

- Cause resonance in power factor correction capacitor banks

- Inject noise into communication systems

- Trigger sensitive ground fault protection devices

- Create electromagnetic interference (EMI) affecting nearby electronic equipment

Modern electronic trip units must filter out these harmonic components to avoid false tripping while maintaining sensitivity to genuine fault conditions.

Inrush Current by Equipment Type

| Equipment Type | Typical Inrush Magnitude | Duration | Primary Cause |

|---|---|---|---|

| Power Transformers | 8-15× rated current | 0.1-1.0 seconds | Core saturation, residual flux |

| Distribution Transformers | 10-15× rated current | 0.1-0.5 seconds | Magnetic flux establishment |

| Induction Motors (DOL) | 5-8× full load current | 0.5-2.0 seconds | Locked rotor, no back-EMF |

| Synchronous Motors | 6-10× full load current | 1.0-3.0 seconds | Starting torque requirements |

| Switching Power Supplies | 10-30× steady state | 1-10 milliseconds | Input capacitor charging |

| LED Drivers | 10-20× operating current | 1-5 milliseconds | Capacitive input stage |

| Incandescent Lamps | 10-15× rated current | 5-50 milliseconds | Cold filament resistance |

| Heating Elements | 1.5-3× rated current | 0.1-1.0 seconds | Cold resistance effect |

| Capacitor Banks | 20-50× rated current | 5-20 milliseconds | Zero initial voltage |

| Variable Frequency Drives | 15-40× operating current | 5-50 milliseconds | DC bus capacitor charging |

How to Calculate Inrush Current

Transformer Inrush Current Calculation

Accurate prediction of transformer inrush current is complex due to the nonlinear behavior of magnetic cores and the influence of residual flux. However, practical estimation methods exist for engineering purposes.

Empirical Method:

I_inrush = K × I_rated

Where:

- K = Inrush factor (typically 8-15 for distribution transformers, 10-20 for large power transformers)

- I_rated = Transformer rated current = kVA / (√3 × kV) for three-phase

Example: A 500 kVA, 480V three-phase transformer:

- I_rated = 500,000 / (√3 × 480) = 601 A

- I_inrush = 12 × 601 = 7,212 A (using K=12)

IEEE/IEC Method with Saturation Factor:

I_inrush = (2 × V_peak × S_f) / (ω × L_m)

Where:

- V_peak = Peak voltage

- S_f = Saturation factor (1.4-2.0, depending on core material and switching angle)

- ω = Angular frequency (2πf)

- L_m = Magnetizing inductance

The saturation factor accounts for worst-case switching at voltage zero-crossing with maximum residual flux in the unfavorable direction.

Motor Inrush Current Calculation

Motor inrush current is typically specified by the manufacturer as the locked-rotor current (LRC) or using a code letter on the nameplate.

Using LRC Ratio:

I_inrush = LRC_ratio × I_full_load

Where LRC_ratio typically ranges from 5.0 to 8.0 for standard induction motors.

Using NEMA Code Letter:

The motor nameplate includes a code letter (A through V) that indicates locked-rotor kVA per horsepower:

I_inrush = (Code_kVA × HP × 1000) / (√3 × Voltage)

For example, a 50 HP, 480V motor with Code Letter G (5.6-6.29 kVA/HP):

- I_inrush = (6.0 × 50 × 1000) / (√3 × 480) = 361 A

Capacitive Load Inrush Calculation

For circuits with significant capacitance:

I_inrush_peak = V_peak / Z_total

Where Z_total includes source impedance, wiring resistance, and any inrush limiting components.

The energy stored in the capacitor during charging:

E = ½ × C × V²

This energy consideration is important for fuse and circuit breaker I²t ratings.

Inrush Current vs. Short Circuit Current

| Characteristic | Inrush Current | Short Circuit Current |

|---|---|---|

| Nature | Transient, self-limiting | Sustained until cleared |

| Magnitude | 2-30× rated current | 10-100× rated current |

| Duration | Milliseconds to seconds | Continuous until protection operates |

| Waveform | Asymmetric, harmonic-rich | Symmetric, fundamental frequency |

| Cause | Normal energization | Insulation failure, fault |

| System Response | Should not trip protection | Must trip protection immediately |

| Predictability | Somewhat predictable | Depends on fault location |

| Equipment Damage | Minimal if properly designed | Severe, potentially catastrophic |

Understanding this distinction is critical for protection coordination and preventing nuisance tripping while maintaining safety.

Mitigation Strategies for Inrush Current

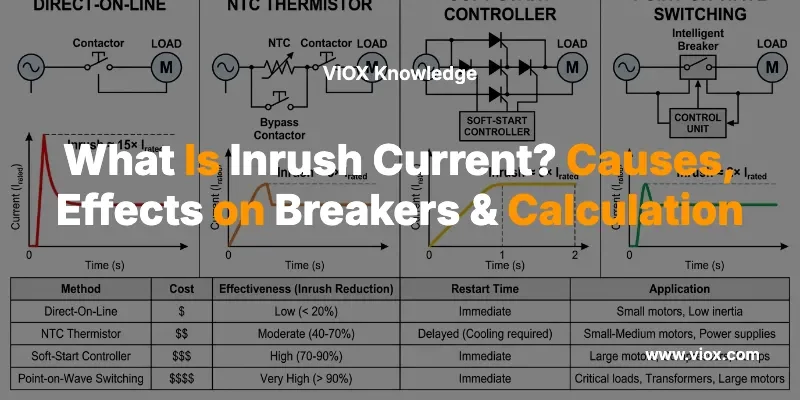

NTC Thermistor Inrush Limiters

Negative Temperature Coefficient (NTC) thermistors provide a simple, cost-effective inrush limiting solution for many applications. These devices exhibit high resistance when cold, limiting initial current flow. As current passes through the thermistor, self-heating reduces its resistance to a negligible level within seconds, allowing normal operation.

Advantages:

- Low cost and simple implementation

- No control circuitry required

- Compact size suitable for PCB mounting

- Effective for capacitive and resistive loads

Limitations:

- Requires cooling time between operations (typically 60+ seconds)

- Not suitable for frequent on-off cycling

- Limited to moderate power levels

- No short-circuit protection capability

NTC thermistors are widely used in switching power supplies, motor drives, and electronic equipment but are less suitable for industrial applications requiring rapid restart capability.

Soft-Start Circuits and Controllers

Soft-start systems gradually apply voltage to the load over a controlled time period, allowing magnetic flux and mechanical inertia to build progressively. For motor applications, soft-starters use thyristor or IGBT power electronics to ramp voltage from zero to full over several seconds.

Benefits:

- Reduces inrush to 2-4× full load current

- Minimizes mechanical shock to driven equipment

- Extends equipment lifespan

- Reduces voltage sag impact on other loads

- Suitable for frequent starts

Considerations:

- Higher cost than direct-on-line starting

- Generates heat during ramp period

- Requires proper sizing and cooling

- May need bypass contactor for continuous operation

Soft-start technology is particularly valuable for large motors, compressors, and conveyor systems where reduced mechanical stress justifies the additional cost.

Pre-Insertion Resistors and Reactors

Some circuit breakers and switchgear incorporate pre-insertion resistors that temporarily insert resistance during closing, then bypass it after flux stabilization. This technique is common in high-voltage circuit breakers for transformer switching.

Similarly, series reactors can limit inrush by adding impedance, though they remain in the circuit during normal operation, causing continuous voltage drop and power loss.

Point-on-Wave Switching

Advanced controlled switching devices synchronize circuit breaker closing with the optimal point on the voltage waveform to minimize inrush. For transformers, closing near the voltage peak (when flux requirement is minimum) can reduce inrush by 50-80%.

This technology requires:

- Real-time voltage monitoring

- Precise timing control (sub-millisecond accuracy)

- Knowledge of residual flux (advanced systems)

- Intelligent electronic controllers

While more expensive, point-on-wave switching provides the most effective inrush reduction for critical applications and is increasingly common in automatic transfer switches and utility substations.

Sequential Energization

In systems with multiple transformers or large loads, staggering the energization sequence prevents cumulative inrush from overwhelming the supply. Time delays of 5-10 seconds between starts allow each transient to decay before the next begins.

This approach is particularly important in:

- Switchgear installations with multiple transformers

- Data centers with numerous UPS systems

- Industrial facilities after power restoration

- Solar combiner boxes with multiple inverters

Proper sequencing logic can be implemented in control panels using timers and interlocking relays.

Circuit Breaker Selection Considerations

Understanding Trip Curves and Inrush Tolerance

Circuit breaker trip curves define the time-current relationship for thermal and magnetic trip elements. For inrush tolerance, the key parameters are:

Thermal Trip Element:

- Responds to I²t heating effect

- Tolerates brief overcurrents

- Typically allows 1.5× rated current indefinitely

- Trips at 2-3× rated current in minutes

Magnetic Trip Element (Instantaneous):

- Responds to current magnitude

- Type B: 3-5× In (residential applications)

- Type C: 5-10× In (commercial/light industrial)

- Type D: 10-20× In (motor and transformer loads)

For transformer protection, Type D curve MCBs or adjustable MCCBs with high instantaneous settings (10-15× In) are typically required to avoid nuisance tripping during energization.

Coordination with Upstream and Downstream Protection

Proper selectivity and coordination ensures that only the circuit breaker closest to a fault operates, while all breakers tolerate inrush from their respective loads. This requires:

- Time-current curve analysis for all protective devices

- Verification that inrush magnitude falls below instantaneous trip settings

- Confirmation that inrush duration is within thermal element tolerance

- Consideration of short-circuit ratings and breaking capacity

Modern electronic trip units offer programmable inrush restraint features that temporarily inhibit tripping during the first few cycles after energization, providing superior discrimination between inrush and fault conditions.

Special Considerations for Different Applications

Motor Protection:

- Use motor protection circuit breakers or MCCBs with motor ratings

- Verify locked-rotor current compatibility

- Consider thermal overload relays for running protection

- Account for frequent start applications

Transformer Protection:

- Select breakers with high instantaneous settings or time-delay

- Consider transformer inrush current magnitude and duration

- Verify compatibility with transformer tap settings

- Account for cold-load pickup scenarios

Electronic Equipment:

- Recognize high capacitive inrush from power supplies

- Use Type C or D curve breakers for large equipment

- Consider surge protection devices for sensitive loads

- Verify compatibility with UPS systems

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: How long does inrush current last?

A: Inrush current duration varies by equipment type. Transformer inrush typically lasts 0.1-1.0 seconds, motor starting current persists for 0.5-3.0 seconds until the rotor reaches operating speed, and capacitive inrush in power supplies decays within 1-50 milliseconds. The exact duration depends on equipment size, design characteristics, and system impedance.

Q: Why doesn’t inrush current always trip circuit breakers?

A: Circuit breakers are designed with time-current characteristics that tolerate brief overcurrents. The thermal element responds to I²t heating over time, while the magnetic instantaneous element has a threshold typically set at 5-20× rated current. Inrush current, though high in magnitude, is usually brief enough that the thermal element doesn’t accumulate sufficient heat, and the magnitude may fall below the instantaneous trip threshold, especially with properly selected Type C or D curve breakers.

Q: Can inrush current damage electrical equipment?

A: While inrush current itself is a normal phenomenon, repeated or excessive inrush can cause cumulative damage. Effects include contact welding in contactors, insulation stress in transformer windings, and accelerated aging of switching devices. Proper inrush mitigation and correctly rated equipment minimize these risks. Modern equipment is designed to withstand thousands of inrush events over its operational lifetime.

Q: What’s the difference between inrush current and starting current?

A: Inrush current is a broader term encompassing the initial surge in any electrical device, while starting current specifically refers to the current drawn by motors during acceleration from standstill to operating speed. All starting current is inrush current, but not all inrush current is starting current—transformers and capacitors experience inrush without any “starting” process.

Q: How do I calculate the inrush current for circuit breaker sizing?

A: For transformers, multiply rated current by 8-15 (use manufacturer data if available). For motors, use the locked-rotor current from the nameplate or multiply full-load current by 5-8. For electronic equipment, consult manufacturer specifications. When sizing circuit breakers, ensure the instantaneous trip setting exceeds peak inrush current, typically requiring Type C (5-10× In) or Type D (10-20× In) curves for inductive loads.

Q: Do LED lights have inrush current?

A: Yes, LED drivers contain capacitive input stages that create inrush current, typically 10-20 times the steady-state current for 1-5 milliseconds. While individual LED fixtures present minimal issues, large installations with hundreds of fixtures can create significant cumulative inrush. This is why dimmer switches and circuit breakers for LED lighting may require derating or special selection.

Conclusion

Inrush current is an inherent characteristic of electrical equipment that must be understood and managed for reliable system operation. While this transient phenomenon cannot be eliminated entirely, proper equipment selection, protection coordination, and mitigation strategies ensure that inrush current remains a manageable design consideration rather than an operational problem.

For electrical engineers and facility managers, the key to success lies in accurate inrush current calculation, appropriate circuit breaker selection, and implementation of cost-effective mitigation where necessary. By understanding the physical mechanisms behind inrush current and applying proven engineering principles, you can design electrical systems that balance protection, reliability, and cost-effectiveness.

Whether you’re specifying MCCBs for industrial panels, coordinating protection for transformer installations, or troubleshooting nuisance tripping issues, a thorough understanding of inrush current fundamentals is essential for professional electrical system design and operation.