On January 5, 2026, the electrical engineering landscape shifted imperceptibly but significantly. During the unveiling of the Vera Rubin AI superchip platform, Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang mentioned a critical infrastructure detail often overlooked by consumer media: the platform’s reliance on Solid State Circuit Breakers (SSCBs) for rack-level protection.

Almost simultaneously, code analysis of Tesla’s v4.52.0 app update revealed references to “AbleEdge,” a proprietary smart breaker logic designed to integrate with Powerwall 3+ systems.

Why are the world’s leading AI and energy companies abandoning 100-year-old mechanical switch technology? The answer lies in the physics of DC power and the intolerance of modern silicon to electrical faults. For VIOX Electric engineers and our partners in the solar and data center sectors, this transition represents the most significant shift in circuit protection since the invention of the Molded Case Circuit Breaker (MCCB).

The Physics Problem: Why Mechanical Breakers Fail in DC Grids

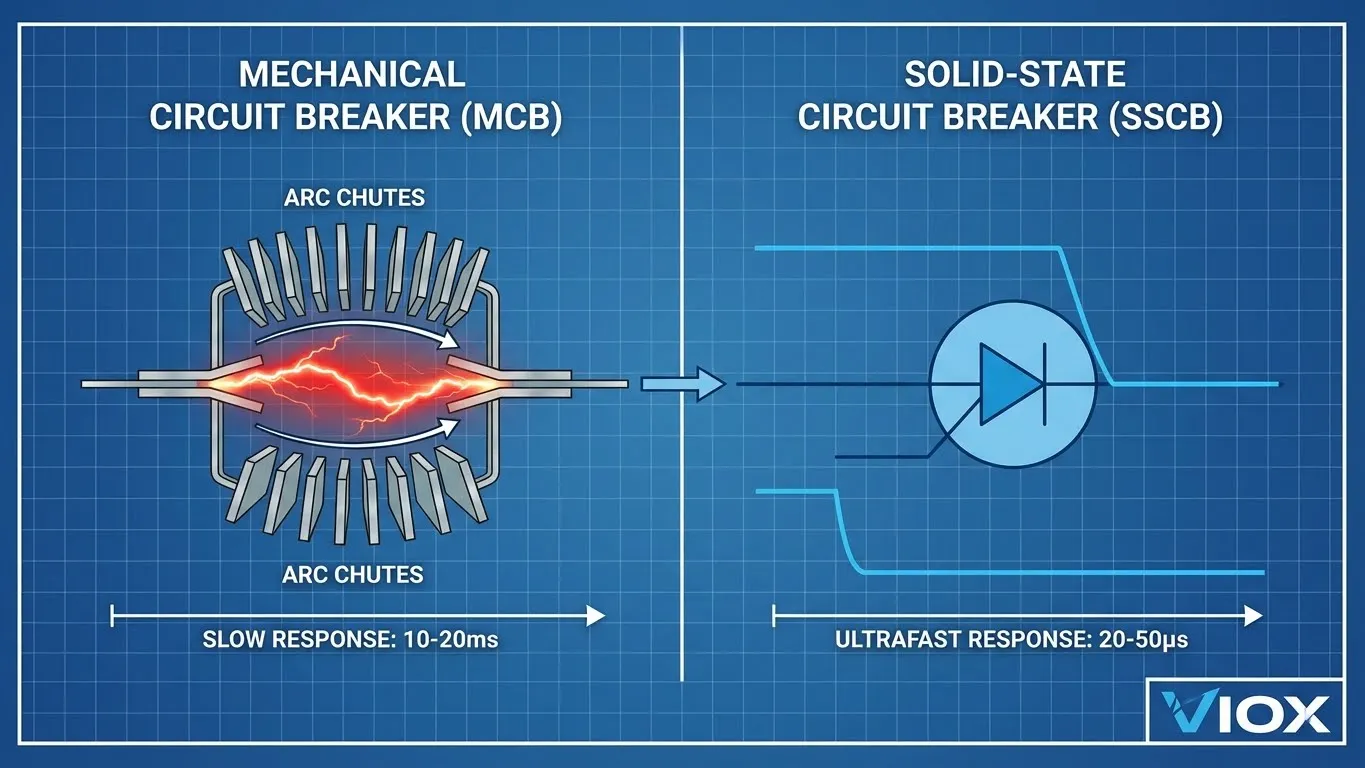

Traditional mechanical circuit breakers were designed for an Alternating Current (AC) world. In AC systems, the current naturally passes through zero 100 or 120 times per second (at 50/60Hz). This “zero-crossing” point provides a natural opportunity to extinguish the electrical arc that forms when contacts separate.

Direct Current (DC) grids have no zero-crossing. When a mechanical breaker attempts to interrupt a high-voltage DC load—common in EV charging stations, solar arrays, and AI server racks—the arc does not self-extinguish. It sustains, generating massive heat (plasma temperatures exceeding 10,000°C) that damages contacts and risks fire.

Furthermore, mechanical breakers are simply too slow. A standard DC circuit breaker relies on a thermal strip or magnetic coil to physically unlatch a spring mechanism. The fastest mechanical clearance times are typically 10 to 20 milliseconds.

In a low-inductance DC microgrid (like inside a server rack or EV charger), fault currents can rise to destructive levels in microseconds. By the time a mechanical breaker trips, the sensitive Insulated Gate Bipolar Transistors (IGBTs) in the inverter or the silicon in the GPU may already be destroyed.

What is a Solid State Circuit Breaker (SSCB)?

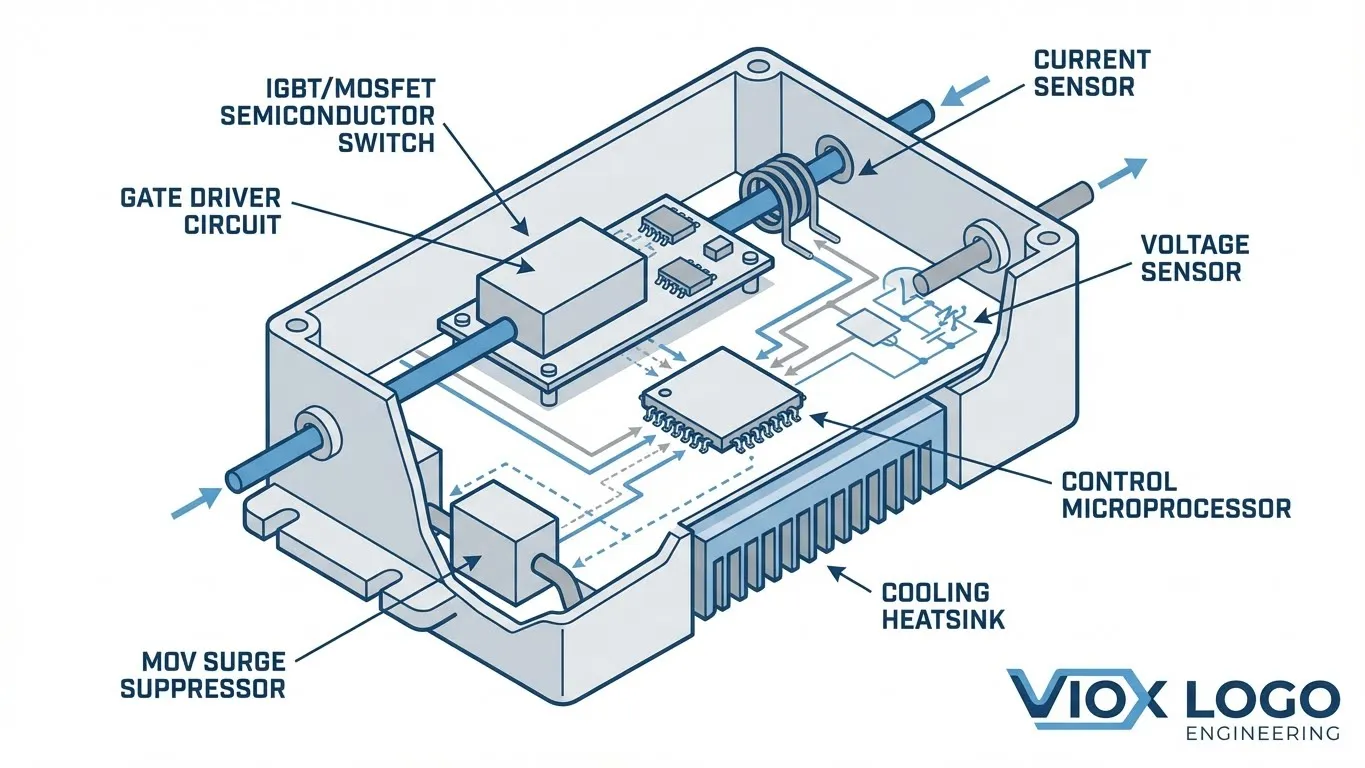

A Solid State Circuit Breaker is a fully electronic protection device that uses power semiconductors to conduct and interrupt current. It contains no moving parts.

Instead of physically separating metal contacts, an SSCB modulates the gate voltage of a power transistor—typically a Silicon IGBT, Silicon Carbide (SiC) MOSFET, or Integrated Gate-Commutated Thyristor (IGCT). When the control logic detects a fault, it removes the gate drive signal, forcing the semiconductor into a non-conductive state almost instantly.

The “Need for Speed”: Microseconds vs. Milliseconds

The definitive advantage of SSCB technology is speed.

- Mechanical Breaker Trip Time: ~10,000 to 20,000 microseconds (10-20ms)

- VIOX SSCB Trip Time: ~1 to 10 microseconds

This 1000x speed advantage means the SSCB effectively “freezes” a short circuit before the current can reach its peak prospective value. This is known as current limiting, but on a scale that mechanical devices cannot achieve.

Comparative Analysis: SSCB vs. Traditional Protection

To understand the positioning of SSCBs in the market, we must compare them directly with existing solutions like fuses and mechanical breakers.

1. Technology Comparison Matrix

| Feature | Fuse | Mechanical Breaker (MCB/MCCB) | Solid State Circuit Breaker (SSCB) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Switching Mechanism | Thermal element melting | Physical contact separation | Semiconductor (IGBT/MOSFET) |

| Response Time | Slow (Thermal dependent) | Medium (10-20ms) | Ultra-Fast (<10μs) |

| Arcing | Contained in sand/ceramic body | Significant Arcing (Requires arc chutes) | No Arcing (Contactless) |

| Reset Capability | None (Single use) | Manual or Motorized | Automatic/Remote (Digital) |

| Maintenance | Replace after fault | Wear on contacts (Electrical endurance limits) | Zero Wear (Infinite operations) |

| Intelligence | None | Limited (Trip curves are fixed) | High (Programmable curves, IoT data) |

| Cost | Low | Medium | High |

2. Semiconductor Technology Selection

The performance of an SSCB depends heavily on the underlying semiconductor material.

| Semiconductor Type | Voltage Rating | Switching Speed | Conduction Efficiency | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silicon (Si) IGBT | High (>1000V) | Fast | Moderate (Voltage drop ~1.5V-2V) | Industrial Drives, Grid Distribution |

| Silicon Carbide (SiC) MOSFET | High (>1200V) | Ultra-Fast | High (Low RDS(on)) | EV Charging, Solar Inverters, AI Racks |

| Gallium Nitride (GaN) HEMT | Medium (<650V) | Fastest | Very High | Consumer Electronics, 48V Telecom |

| IGCT | Very High (>4.5kV) | Moderate | Moderate | MV/HV Transmission |

Key Applications Driving Adoption

AI Data Centers (Nvidia Use Case)

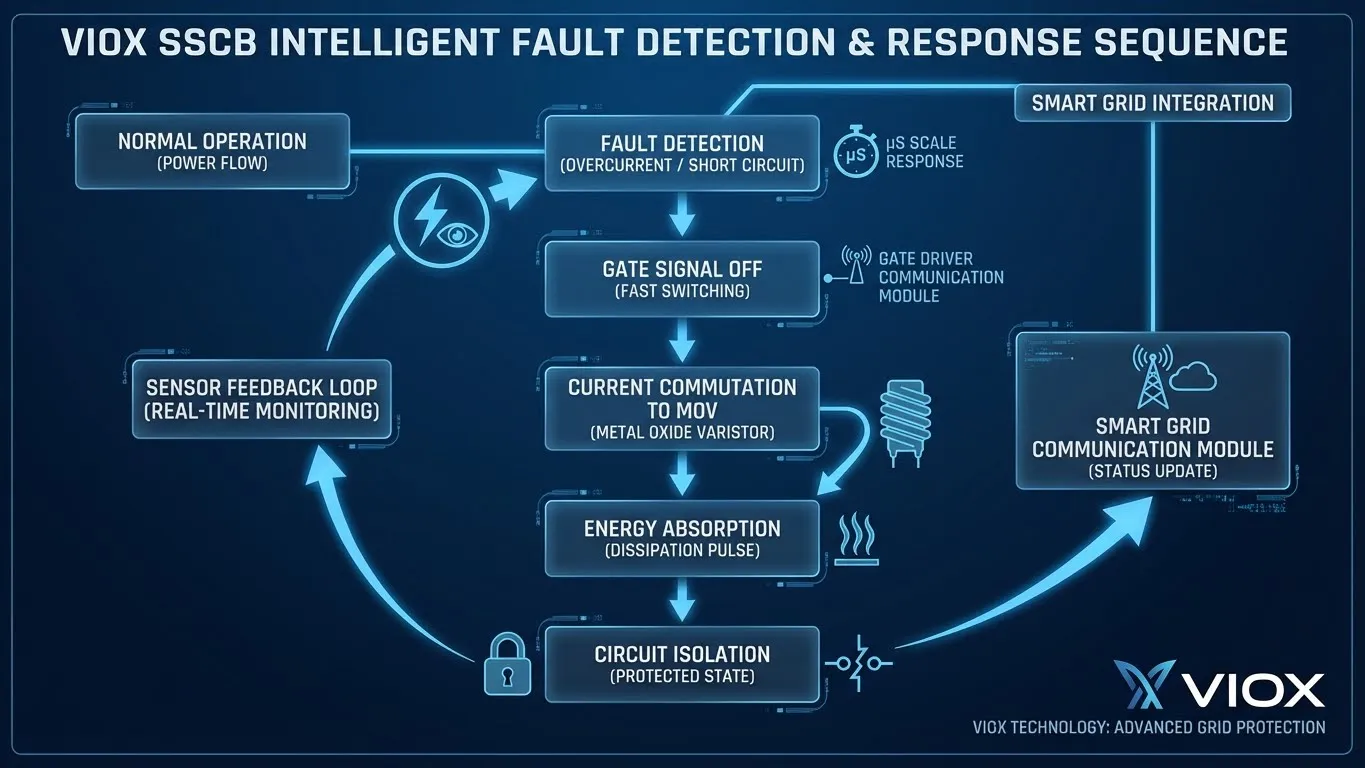

Modern AI clusters, like those running the Vera Rubin chips, consume Megawatts of power. A short circuit in one rack can draw down the voltage of the common DC bus, causing adjacent racks to reboot—a scenario known as a “cascading failure.”

SSCBs isolate faults so quickly that the voltage on the main bus doesn’t drop significantly, allowing the rest of the data center to continue calculating without interruption. This is often referred to as “Ride-Through” capability.

EV Charging and Smart Grids (Tesla Use Case)

As we move toward Bidirectional Charging (V2G), power must flow both ways. Mechanical breakers are directional or require complex configurations to handle bidirectional arcs. SSCBs can be designed with back-to-back MOSFETs to handle bidirectional power flow seamlessly. Additionally, the smart features allow the breaker to act as a utility-grade meter, reporting real-time consumption data to the grid operator.

Solar Photovoltaic (PV) Systems

In PV DC protection, distinguishing between a normal load current and a high-impedance arc fault is difficult for thermal-magnetic breakers. SSCBs use advanced algorithms to analyze the current waveform (di/dt) and detect arc signatures that thermal breakers miss, preventing roof fires.

Technical Deep Dive: Inside the VIOX SSCB

An SSCB is not just a switch; it is a computer with a power stage.

- The Switch: A matrix of SiC MOSFETs provides the low-resistance path for current.

- The Snubber/MOV: Because inductive loads fight against sudden current stops (Voltage = L * di/dt), a Metal Oxide Varistor (MOV) is placed in parallel to absorb the flyback energy and clamp voltage spikes.

- The Brain: A microcontroller samples current and voltage at megahertz frequencies, comparing them against programmable trip curves.

The Thermal Challenge

The main drawback of SSCBs is Conduction Loss. Unlike a mechanical contact which has near-zero resistance, semiconductors have an “On-State Resistance” (RDS(on)).

- Example: If an SSCB has a resistance of 10 milliohms and carries 100A, it generates I2R losses: 1002 × 0.01 = 100 Watts of heat.

This necessitates active cooling or large heatsinks, which affects the physical footprint compared to standard breaker sizes.

Deployment Strategy for Installers

For EPCs and installers looking to integrate SSCB technology, we recommend a hybrid approach during this transition period.

3. Application Triage Matrix

| Application | Recommended Protection | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Grid Main Entrance (AC) | Mechanical / MCCB | High current, low switching frequency, mature cost. |

| Solar String Combiner (DC) | Fuse / DC MCB | Cost-sensitive, simple protection needs. |

| Battery Storage (ESS) | SSCB or Hybrid | Needs fast bi-directional switching and arc flash reduction. |

| EV Fast Charger (DC) | SSCB | Critical safety, high voltage DC, repetitive switching. |

| Sensitive Loads (Server/Medical) | SSCB | Requires microsecond protection to save equipment. |

Future Trends: The Hybrid Breaker

While pure SSCBs are ideal for low/medium voltage, Hybrid Circuit Breakers are emerging for higher power applications. These devices combine a mechanical switch for low-loss conduction and a parallel solid-state branch for arc-less switching. This offers the “best of both worlds”: the efficiency of mechanical contacts and the speed/arcless operation of semiconductors.

As Silicon Carbide manufacturing costs decrease (driven by the EV industry), the price parity between high-end electronic MCCBs and SSCBs will narrow, making them standard for commercial vs residential EV charging protection.

FAQ

What is the main difference between SSCB and traditional circuit breakers?

The main difference is the switching mechanism. Traditional breakers use moving mechanical contacts that physically separate to break the circuit, while SSCBs use power semiconductors (transistors) to stop current flow electronically without any moving parts.

Why are SSCBs faster than mechanical breakers?

Mechanical breakers are limited by the physical inertia of springs and latches, taking 10-20 milliseconds to open. SSCBs operate at the speed of electron flow control, responding to gate signals in microseconds (1-10μs), which is roughly 1000 times faster.

Are solid-state circuit breakers suitable for solar PV systems?

Yes, they are highly suitable for DC solar strings. They eliminate the DC arcing risk inherent in mechanical switches and can provide advanced arc-fault detection (AFCI) capabilities that traditional thermal-magnetic breakers cannot match.

What are the disadvantages of SSCBs?

The primary disadvantages are higher initial cost and constant power loss (heat generation) during operation due to the internal resistance of the semiconductors. This requires heat sinks and careful thermal management design.

How long do SSCBs last compared to mechanical breakers?

Since they have no moving parts to wear out and generate no electrical arcs to erode contacts, SSCBs have a virtually infinite operational lifespan for switching cycles, whereas mechanical breakers are typically rated for 1,000 to 10,000 operations.

Do SSCBs require special cooling?

Yes, typically. Because semiconductors generate heat when current flows through them (I2R losses), SSCBs usually require passive aluminum heatsinks, and for very high-current applications, they may require active cooling fans or liquid cooling plates.