Vous ouvrez un contrôleur de maison intelligente moderne et de haute technologie. Il est rempli de composants microscopiques à montage en surface, de microprocesseurs puissants et de puces Wi-Fi.

Et puis, juste au milieu de tout ce silicium, se trouve un gros cube de plastique volumineux. Lorsqu'il s'active, il fait un fort CLIC.

C'est un relais mécanique. Une technologie des années 1830.

Cela soulève une question “existentielle” pour tout ingénieur : Dans un monde où les MOSFET et les IGBT sont bon marché, microscopiques et silencieux, pourquoi n'avons-nous pas éliminé le relais ?

Pourquoi se fier à un bras métallique mobile maintenu par un ressort alors que nous avons la physique de l'état solide ?

La réponse n'est pas la nostalgie, mais une réalité d'ingénierie froide et dure. Il s'avère que le relais “maladroit” a une superpuissance que le silicium ne peut tout simplement pas reproduire.

Décomposons la bataille entre le Commutateur dur (relais) et le Commutateur souple (transistor).

1. La sécurité de la “lame d'air” : pourquoi les relais sont le pare-feu ultime

La raison pour laquelle les relais sont toujours rois est un concept appelé Isolation galvanique.

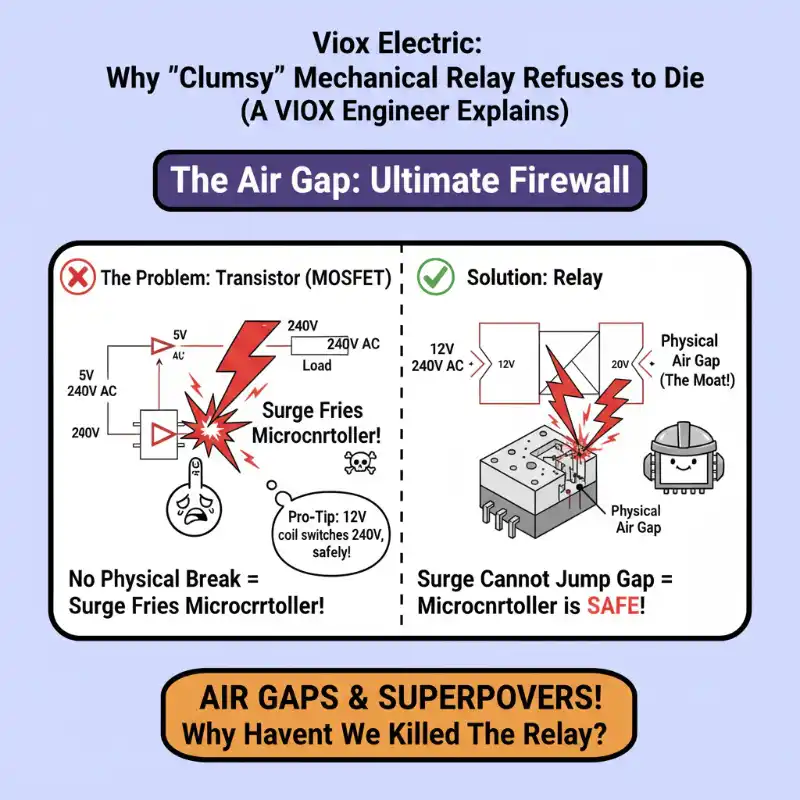

Pensez à un MOSFET (transistor). Même lorsqu'il est “OFF”, il existe toujours une connexion physique et chimique entre la charge haute tension et votre microcontrôleur sensible. Ils partagent un morceau de silicium. Souvent, ils doivent partager une référence de “masse”.

Si ce MOSFET tombe en panne de manière catastrophique (par exemple, une pointe de tension perce l'oxyde de grille), cette alimentation secteur de 240 V ne reste pas seulement du côté de la charge. Elle voyage à l'envers, directement dans votre Arduino ou Raspberry Pi de 5 V.

Le résultat ? Votre microprocesseur est instantanément grillé.

L'avantage du relais

Un relais n'a aucune connexion électrique entre la bobine (côté commande) et les contacts (côté charge). Ils sont couplés uniquement par un champ magnétique. À l'intérieur du boîtier, il y a un Lame d'air.

- Le scénario : Votre moteur de 240 V se court-circuite et renvoie une surtension massive sur la ligne.

- Le relais : Les contacts peuvent se souder. Le boîtier en plastique peut fondre. Mais votre microcontrôleur ? Il est en sécurité. La surtension ne peut pas franchir la lame d'air jusqu'à la bobine.

Pro-Tip: Nous appelons cela le “fossé”. Si vous concevez un circuit où la logique de commande doit survivre même si le côté charge explose, vous avez besoin d'un relais. C'est la couche sacrificielle ultime.

Il existe une maxime d'ingénierie classique : “Vous pouvez utiliser une bobine de 12 V pour commuter une ligne secteur de 240 V, sans jamais vous soucier de la différence de tension.” C'est la puissance du Contact sec.

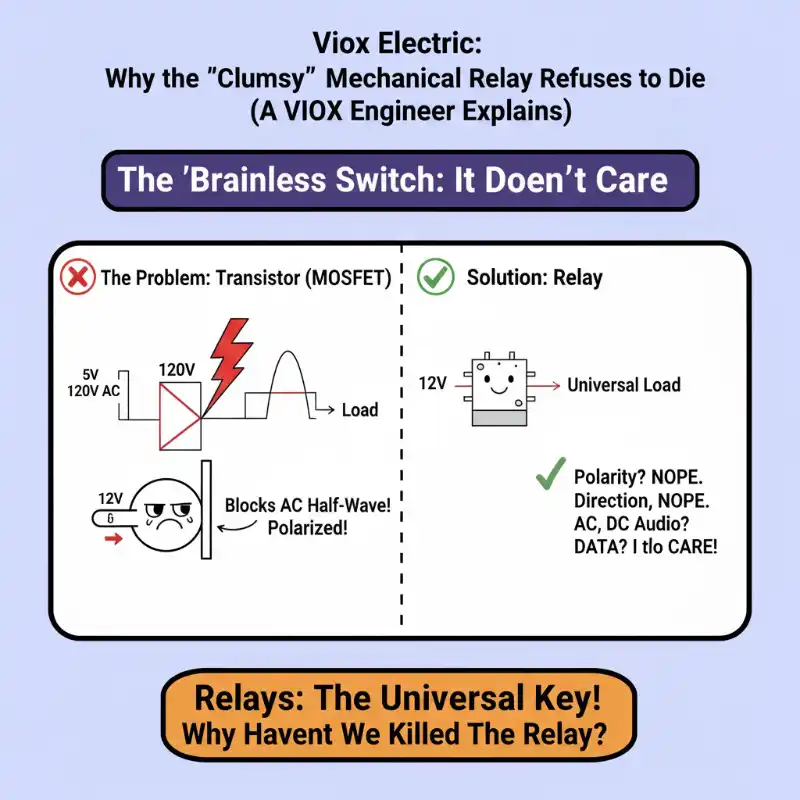

2. Le commutateur “sans cervelle” : CA, CC, il s'en fiche

Les transistors sont capricieux. Ce sont des dispositifs semi-conducteurs, ce qui signifie qu'ils ont des règles.

- BJT/MOSFET sont intrinsèquement CC (courant continu) dispositifs. Ils permettent au courant de circuler dans une seule direction (Drain vers Source).

- Le Problème: Si vous voulez commuter 120 V CA (courant alternatif) avec un MOSFET, vous avez un casse-tête. Le courant inverse sa direction 60 fois par seconde. Un seul MOSFET bloquera la moitié de l'onde et agira comme une diode sur l'autre moitié. Vous avez besoin de deux MOSFET dos à dos, ou d'un Triac, plus un circuit de commande complexe.

L'avantage du relais

Un relais, ce sont juste deux morceaux de métal qui se touchent.

- Polarité : Il s'en fiche.

- Direction : Il s'en fiche.

- Type de tension : CA ? CC ? Signaux audio ? Données ? Il s'en fiche.

Lorsque vous donnez à un client une sortie relais, vous lui donnez une clé universelle. Il peut brancher un solénoïde de 24 V CC, un ventilateur de 120 V CA ou un signal audio de niveau millivolt. Le relais les gère tous avec une chute de tension nulle et un courant de “fuite” nul.

Pro-Tip: Si vous ne savez pas ce ce que l'utilisateur va connecter à votre sortie, utilisez un relais. Une sortie transistor exige que l'utilisateur fasse correspondre parfaitement la tension et la polarité. Un relais dit simplement : “Je connecte A à B.”

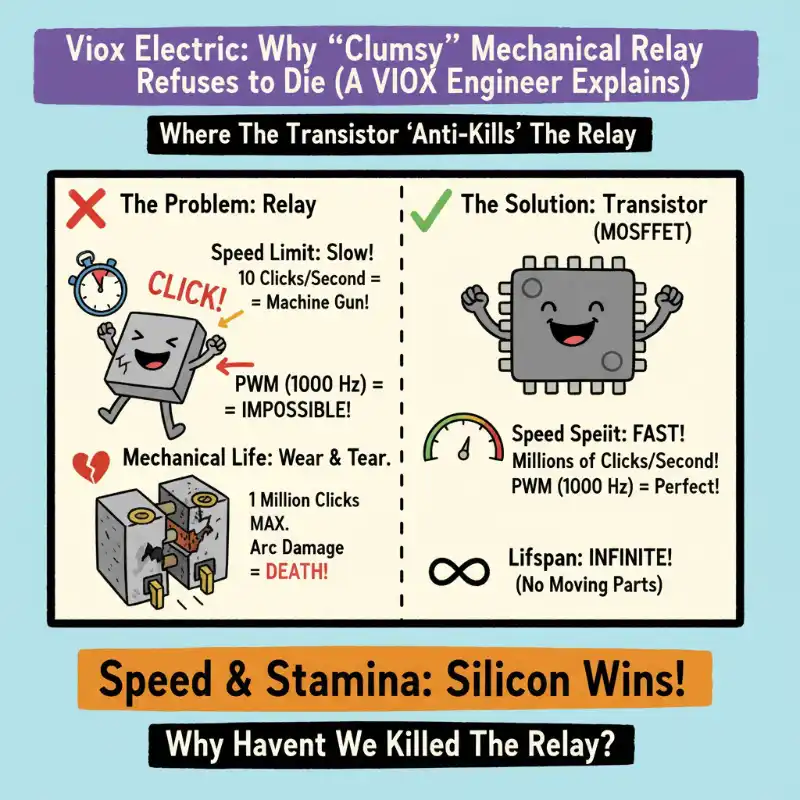

3. Où le transistor “anti-tue” le relais

Alors, si les relais sont si géniaux, pourquoi ne les utilisons-nous pas dans nos téléphones ou nos ordinateurs ?

Parce que les relais ont deux défauts fatals : Vitesse et Usure.

La limite de vitesse

Un relais est un bras mécanique qui se déplace dans l'espace.

- Vitesse du relais : ~50 à 100 millisecondes. Fréquence de commutation maximale : peut-être 10 fois par seconde (10 Hz).

- Vitesse du transistor : Nanosecondes. Fréquence de commutation maximale : Millions de fois par seconde (MHz).

Si vous avez besoin de faire varier l'intensité d'une LED en utilisant la MLI (modulation de largeur d'impulsion), où vous allumez et éteignez l'alimentation 1 000 fois par seconde, un relais est inutile. Il sonnerait comme une mitrailleuse pendant environ 10 minutes avant de se désintégrer.

Le nombre de morts

Un relais a une durée de vie limitée.

- Durée de vie mécanique : Chaque fois qu'il clique, le ressort se fatigue et le pivot s'use. Un bon relais peut durer 1 million de cycles.

- Durée de vie électrique : Chaque fois qu'il s'ouvre sous charge, un petit arc pique les contacts. À pleine charge, il peut ne durer que 100 000 cycles.

Un MOSFET, s'il est maintenu au frais et dans les spécifications, a une durée de vie théoriquement infinie. Il ne s'use pas.

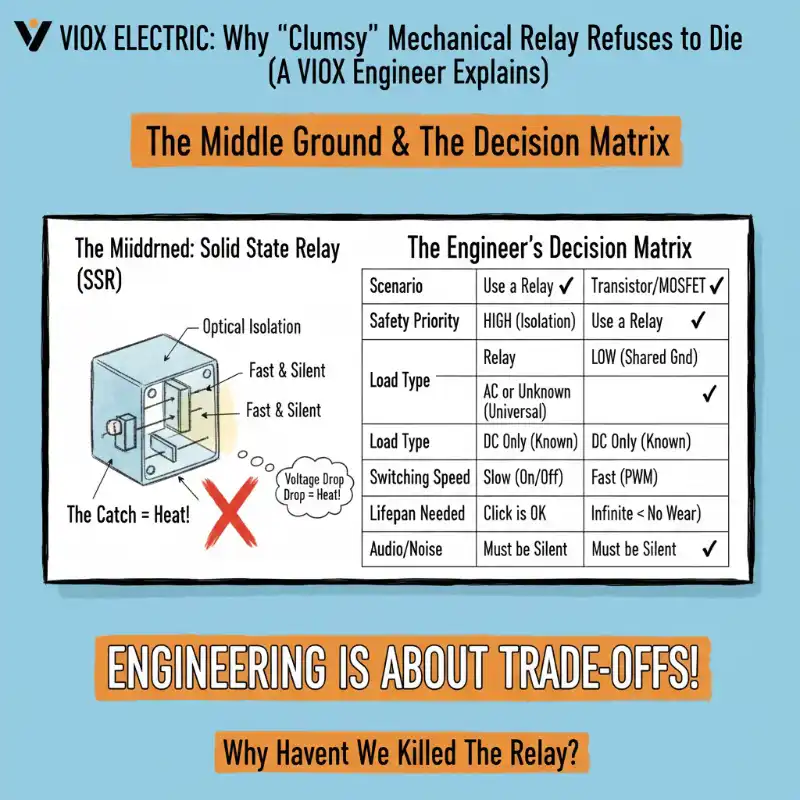

4. Le juste milieu : Le relais statique (SSR)

“ Mais attendez ”, dites-vous. “ Qu'en est-il des relais statiques ? ”

Le SSR est “ l'hybride ”. Il utilise une LED interne pour déclencher un semi-conducteur photosensible.

- Il a une isolation : Oui (isolation optique).

- Il a une vitesse : Oui (plus rapide que mécanique, plus lent que MOSFET nu).

- Il a le silence : Oui.

Le hic : la chaleur.

Un relais mécanique a une résistance quasi nulle (milliohms). Un SSR a une chute de tension (généralement de 0,7 V à 1,5 V) à travers sa sortie.

Pousser 10 ampères à travers un relais mécanique ? Il reste froid.

Pousser 10 ampères à travers un SSR ? Il génère 15 watts de chaleur. Vous avez besoin d'un dissipateur thermique massif pour l'empêcher de fondre.

Résumé : La matrice de décision de l'ingénieur

Ainsi, le clic “ maladroit ” ne disparaît pas. C'est un choix d'ingénierie délibéré. Voici votre aide-mémoire pour savoir quand s'en tenir à l'ancienne technologie :

| Scenario | Utilisez un relais | Utilisez un transistor/MOSFET |

|---|---|---|

| Priorité de sécurité | HAUT (Besoin d'isolation galvanique) | FAIBLE (La masse partagée est OK) |

| Le Type De Charge | AC ou inconnu (Universel) | DC uniquement (Charge connue) |

| Vitesse de commutation | Lent (Marche/Arrêt occasionnellement) | Rapide (PWM / Haute fréquence) |

| Durée de vie nécessaire | Finie (<100k cycles) | Infinie (Millions de cycles) |

| Audio/Bruit | Le clic est OK | Doit être silencieux |

En ingénierie, “ Plus récent ” n'est pas toujours “ Mieux ”. Parfois, la meilleure solution est encore une bobine de cuivre, un ressort en acier et un satisfaisant clic.

Précision Technique Note

Résistance de contact : Les relais mécaniques ont généralement une résistance de contact de l'ordre de 50 mΩ à 100 mΩ, ce qui est négligeable pour la perte de puissance, mais peut être un problème pour les signaux à très basse tension (courant de mouillage requis).

Fuite : Les transistors/SSR ont toujours un minuscule courant de fuite lorsqu'ils sont éteints. Les relais ont zéro fuite (résistance infinie) lorsqu'ils sont ouverts.

Actualité: Les principes de la commutation électromécanique par rapport à la commutation statique sont des principes physiques fondamentaux et restent d'actualité en novembre 2025.