Direct Answer: Why Stainless Steel Doesn’t Rust

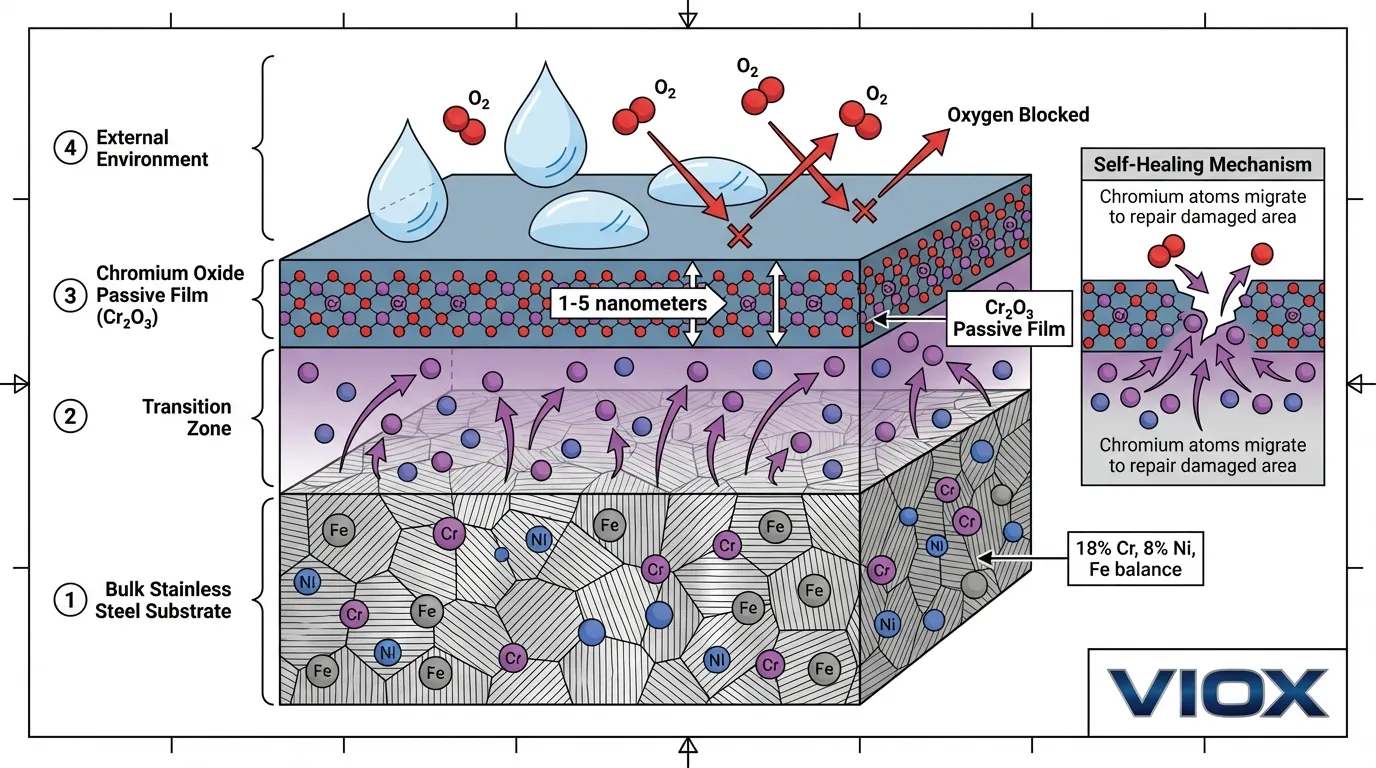

Stainless steel enclosures resist corrosion not because they are “noble” metals like gold or platinum, but through a dynamic protective mechanism called passivation. When stainless steel containing at least 12% chromium is exposed to oxygen, it instantly forms an ultra-thin (1-5 nanometers), transparent chromium oxide layer (Cr₂O₃) on its surface. This passive film acts as an impermeable barrier that prevents corrosive agents—water, oxygen, chlorides, and acids—from reaching the underlying metal. The film is self-healing: if scratched or damaged, chromium atoms from the bulk metal migrate to the surface and spontaneously reform the protective layer within hours when exposed to oxygen. Nickel, typically added at 8-10% in austenitic grades like 304 and 316, extends this protection to reducing (non-oxidizing) acidic environments where chromium oxide alone would dissolve, while also stabilizing the austenitic crystal structure that enhances mechanical properties and uniform film formation.

This article explains the electrochemical paradox of stainless steel, the molecular mechanisms behind passivation, and practical implications for electrical enclosure selection in industrial environments.

The Electrochemical Paradox: Why “Active” Metals Don’t Corrode

Understanding Standard Electrode Potential

Standard electrode potential measures a metal’s tendency to lose electrons (oxidize) in aqueous solution. The more negative the potential, the more “active” or reactive the metal. Metals with positive potentials are considered “noble” and resist oxidation.

Standard Electrode Potentials at 25°C (vs. Standard Hydrogen Electrode)

| Metal/Ion System | Standard Potential (V) | Reactivity Classification |

|---|---|---|

| Gold (Au³⁺/Au) | +1.50 | Highly noble (inert) |

| Platinum (Pt²⁺/Pt) | +1.18 | Noble |

| Silver (Ag⁺/Ag) | +0.80 | Noble |

| Copper (Cu²⁺/Cu) | +0.34 | Moderately noble |

| Hydrogen (H⁺/H₂) | 0.00 | Reference standard |

| Nickel (Ni²⁺/Ni) | -0.23 | Active metal |

| Iron (Fe²⁺/Fe) | -0.44 | Active metal |

| Chromium (Cr³⁺/Cr) | -0.74 | Highly active metal |

| Zinc (Zn²⁺/Zn) | -0.76 | Highly active |

| Aluminum (Al³⁺/Al) | -1.66 | Extremely active |

The paradox becomes clear: stainless steel’s primary components—iron, chromium, and nickel—all have negative electrode potentials, indicating they should corrode readily. Chromium, at -0.74V, is even more reactive than iron (-0.44V). From pure thermodynamic perspective, these metals should oxidize aggressively when exposed to moisture and oxygen.

Yet 304 stainless steel (18% chromium, 8% nickel) and 316 stainless steel (16% chromium, 10% nickel, 2% molybdenum) demonstrate exceptional corrosion resistance in environments where carbon steel would rust completely within months.

The resolution: Stainless steel’s corrosion resistance is not thermodynamic (inherent stability) but kinetic (protective barrier formation). The metals are still reactive, but their reaction products form a protective shield that dramatically slows further corrosion.

The Passivation Mechanism: Chromium’s Critical Role

Formation of the Chromium Oxide Layer

When stainless steel is exposed to oxygen—whether from air, water, or oxidizing chemicals—chromium atoms at the surface undergo rapid oxidation:

4Cr + 3O₂ → 2Cr₂O₃

This reaction occurs within milliseconds of exposure, forming a continuous chromium oxide film. The film’s remarkable properties include:

- Density and Structure: The Cr₂O₃ layer is amorphous (non-crystalline) and extremely dense, with a structure that effectively blocks diffusion of oxygen, water molecules, and corrosive ions toward the underlying metal substrate.

- Thickness: Typically 1-5 nanometers (0.001-0.005 micrometers)—invisible to the naked eye but sufficient to provide robust protection. For reference, a human hair is approximately 80,000 nanometers in diameter.

- Adhesion: The oxide layer bonds strongly to the metal substrate through chemical bonding at the metal-oxide interface, preventing delamination even under mechanical stress.

- Self-Healing Capability: The most critical property. When the passive film is damaged by scratching, abrasion, or localized chemical attack, chromium from the bulk alloy migrates to the damaged area and reacts with available oxygen to reform the protective layer. This regeneration typically occurs within 24-48 hours in air and can happen within minutes in highly oxygenated environments.

Why Iron Oxide Fails Where Chromium Oxide Succeeds

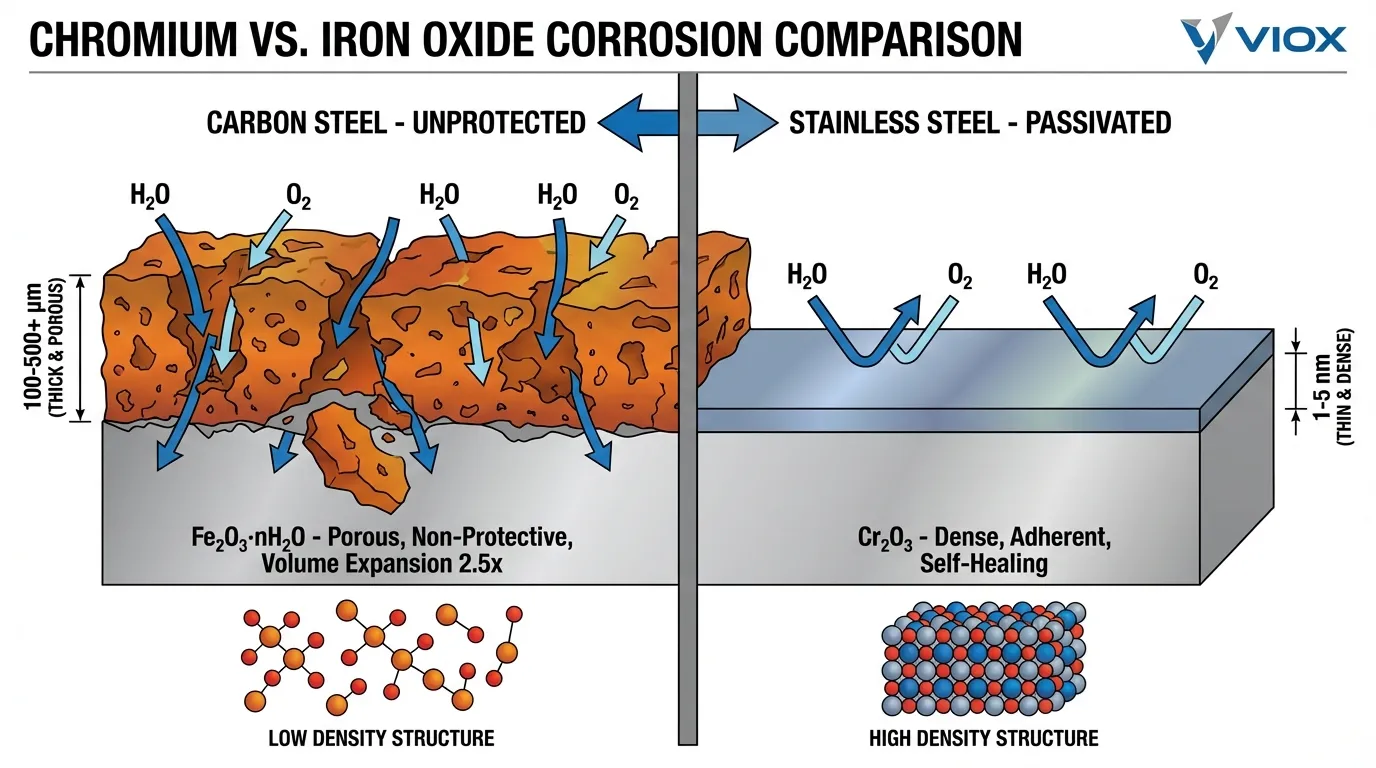

The contrast with ordinary carbon steel is instructive. When iron oxidizes, it forms iron oxide (Fe₂O₃·nH₂O)—commonly known as rust. This material has fundamentally different properties:

- Porous Structure: Iron oxide is loosely packed with interconnected pores that allow continued penetration of water and oxygen to the underlying metal.

- Volume Expansion: Iron oxide occupies approximately 2.5 times the volume of the iron from which it formed. This expansion creates internal stresses that cause the oxide to crack and spall (flake off), continuously exposing fresh metal to corrosion.

- Non-Adherent: The oxide layer does not bond strongly to the substrate and readily detaches, providing no long-term protection.

- Progressive Degradation: Rust formation is self-accelerating. As the oxide layer builds up and flakes off, corrosion penetrates deeper into the metal until structural failure occurs.

In contrast, chromium oxide is compact, adherent, and self-maintaining—transforming a thermodynamically active metal into a kinetically protected one.

The 12% Chromium Threshold

Extensive research has established that stainless steel requires a minimum of 12% chromium by weight to form a continuous, stable passive film. Below this threshold, the chromium oxide islands are discontinuous, leaving gaps where iron can oxidize and initiate corrosion. Above 12%, the passive film becomes increasingly robust:

- 12-14% Cr: Basic corrosion resistance in mild environments (ferritic grades like 410, 430)

- 16-18% Cr: Enhanced resistance suitable for most industrial applications (austenitic 304: 18% Cr, 8% Ni)

- 16-18% Cr + 2-3% Mo: Superior resistance to chlorides and acids (austenitic 316: 16% Cr, 10% Ni, 2% Mo)

Higher chromium content increases the chromium-to-iron ratio in the passive film, making it more stable and resistant to breakdown in aggressive environments.

Nickel’s Dual Role: Corrosion Protection and Structural Stabilization

Protection in Reducing Environments

While chromium oxide excels in oxidizing environments (air, nitric acid, oxidizing salts), it is vulnerable in reducing (non-oxidizing) acidic conditions. In dilute sulfuric acid or hydrochloric acid, the Cr₂O₃ film can dissolve, exposing the base metal to attack.

Nickel addresses this limitation through two mechanisms:

- Inherent Acid Resistance: Nickel’s electrode potential (-0.23V) is less negative than iron (-0.44V) or chromium (-0.74V), making it inherently more resistant to acid attack. When nickel is alloyed into stainless steel, it provides a “buffer” that slows corrosion even when the chromium oxide film is compromised.

- Passive Film Modification: Nickel incorporates into the passive film structure, creating a mixed chromium-nickel oxide layer. This modified film demonstrates improved stability in reducing acids compared to pure chromium oxide.

The practical result: austenitic stainless steels containing 8-10% nickel (like 304 and 316) resist a much broader range of corrosive media than ferritic grades (which contain chromium but little or no nickel).

Austenite Stabilization and Mechanical Properties

Nickel’s second critical function is metallurgical. In the iron-chromium-nickel system, nickel is an “austenite stabilizer”—it promotes formation of the face-centered cubic (FCC) crystal structure known as austenite, which remains stable at room temperature.

Why austenite matters for corrosion resistance:

- Uniform Microstructure: Austenitic stainless steels have a single-phase structure without the ferrite-martensite boundaries present in other grades. Grain boundaries and phase interfaces are preferential sites for corrosion initiation. Fewer boundaries mean fewer weak points.

- Enhanced Ductility: The austenitic structure provides excellent formability and toughness, allowing fabrication of complex enclosure geometries without cracking or work-hardening issues that could compromise the passive film.

- Non-Magnetic Properties: Austenitic grades are non-magnetic, which is advantageous in electrical enclosures housing sensitive instrumentation or in applications where magnetic permeability must be minimized.

- Cryogenic Performance: Austenitic stainless steels maintain ductility and toughness at extremely low temperatures, unlike ferritic and martensitic grades that become brittle. This makes 304 and 316 suitable for cryogenic applications.

Typical austenitic compositions require 8-10% nickel to stabilize the austenite phase in 18% chromium steels. Lower nickel content results in partial transformation to ferrite or martensite, which can reduce corrosion resistance and toughness.

Comparing Stainless Steel Grades for Electrical Enclosures

304 Stainless Steel: The General-Purpose Workhorse

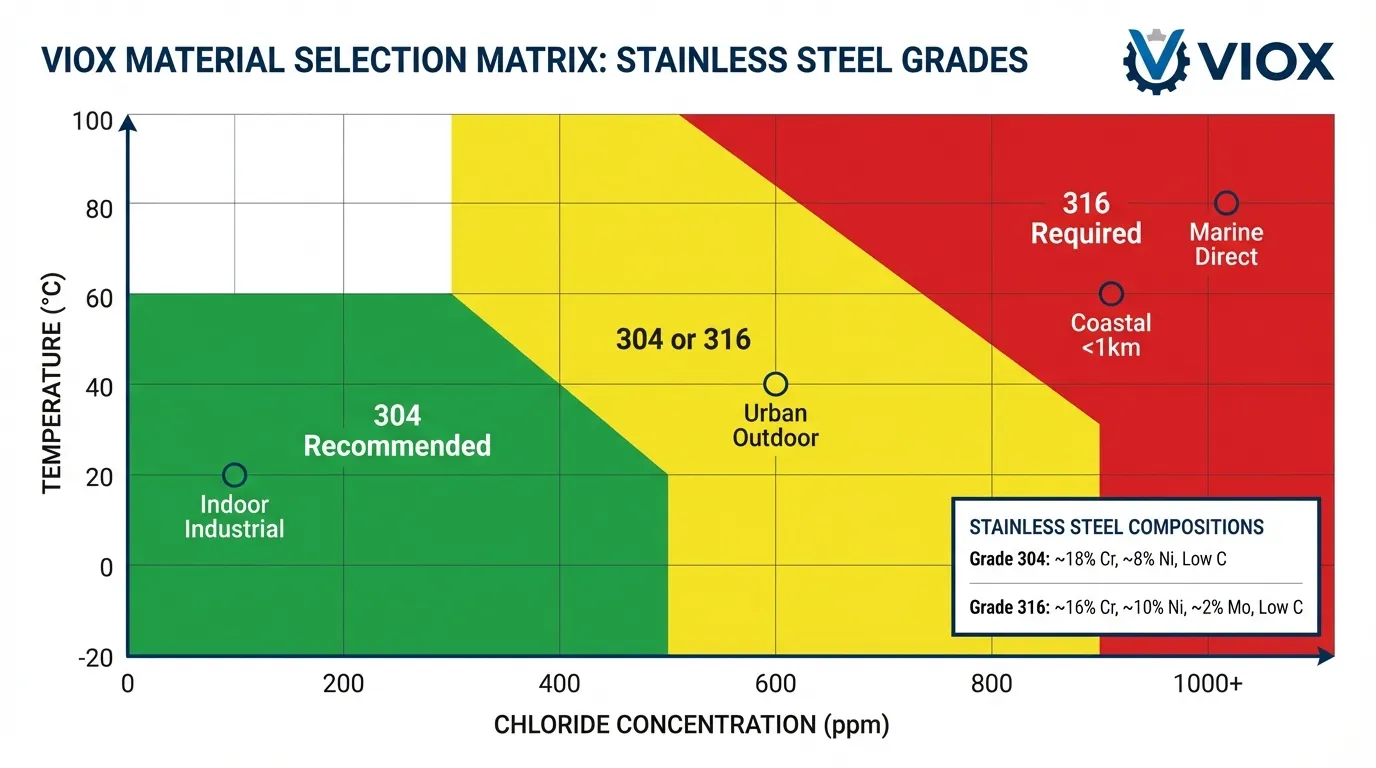

Composition: 18% Cr, 8% Ni, balance Fe (often called “18-8” stainless)

Passivation Characteristics:

- Forms stable Cr₂O₃ passive film in air and most aqueous environments

- Self-healing in oxidizing conditions

- Resistant to atmospheric corrosion, food acids, organic chemicals, and many inorganic chemicals

Optimal Applications:

- Indoor electrical enclosures in industrial facilities

- Food and beverage processing equipment

- Pharmaceutical manufacturing environments

- Urban outdoor installations (non-coastal)

- General-purpose NEMA 4X enclosures

Limitations:

- Susceptible to pitting and crevice corrosion in high-chloride environments (>100 ppm Cl⁻)

- Not recommended for direct coastal exposure or marine applications

- Can experience stress corrosion cracking in hot chloride solutions

Cost: Moderate (20-35% premium over carbon steel)

316 Stainless Steel: Enhanced Chloride Resistance

Composition: 16% Cr, 10% Ni, 2-3% Mo, balance Fe

Passivation Characteristics:

- Molybdenum enrichment in passive film provides superior resistance to chloride-induced pitting

- Enhanced film stability in acidic environments

- Maintains passivity in higher chloride concentrations (up to 1000 ppm)

Optimal Applications:

- Coastal and marine electrical installations

- Chemical processing plants handling chlorinated compounds

- Wastewater treatment facilities

- Offshore oil and gas platforms

- Areas with de-icing salt exposure

- High-chloride washdown environments

Limitations:

- Higher cost (60-100% premium over carbon steel, 30-40% over 304)

- Slightly more difficult to machine and form than 304

Cost: High (but justified by extended service life in harsh environments)

Material Selection Decision Matrix

| Environment | Chloride Exposure | Temperature | Recommended Grade | Expected Service Life |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indoor controlled | <50 ppm | 0-60°C | 304 | 30-40 years |

| Urban outdoor | 50-100 ppm | -20 to 60°C | 304 | 25-30 years |

| Light industrial | 100-200 ppm | 0-80°C | 304 or 316 | 20-30 years |

| Coastal (>1 km from ocean) | 200-500 ppm | -10 to 60°C | 316 | 25-35 years |

| Coastal (<1 km from ocean) | 500-1000 ppm | -10 to 60°C | 316 | 20-30 years |

| Direct marine exposure | >1000 ppm | -10 to 60°C | 316L or duplex | 15-25 years |

| Chemical processing | Variable | 0-100°C | 316 or higher alloy | 15-30 years |

Passivation in Practice: Manufacturing and Maintenance

Manufacturing Passivation Treatments

During fabrication—welding, machining, forming—the natural passive film can be damaged or contaminated with free iron particles from tools. Manufacturing passivation treatments restore optimal corrosion resistance:

Citric Acid Passivation (ASTM A967):

- Environmentally friendly, non-toxic process

- Selectively removes free iron while preserving chromium and nickel

- Typical treatment: 4-10% citric acid at 21-66°C for 4-30 minutes

- Preferred for 304 and 316 grades in most applications

Nitric Acid Passivation (ASTM A967, AMS 2700):

- Traditional method using 20-25% nitric acid at 49-66°C

- More aggressive oxidation accelerates passive film formation

- Required for high-carbon grades or heavily contaminated surfaces

- Environmental and safety concerns have reduced usage

Electropolishing:

- Electrochemical process that removes a thin surface layer (5-25 micrometers)

- Produces ultra-smooth surface with enhanced passive film

- Increases chromium-to-iron ratio at surface

- Premium treatment for pharmaceutical, semiconductor, and critical applications

After passivation, the enclosure should be thoroughly rinsed with deionized water and allowed to air-dry. The passive film fully develops over 24-48 hours as chromium at the surface reacts with atmospheric oxygen.

Field Maintenance and Passive Film Restoration

Properly specified stainless steel enclosures require minimal maintenance, but periodic inspection ensures long-term performance:

- Quarterly Visual Inspection: Check for surface contamination (iron deposits, organic buildup), verify gasket integrity, and look for discoloration.

- Annual Cleaning: Remove surface deposits with mild detergent and water. The cleaning process itself helps restore the passive film by exposing fresh chromium to oxygen.

- Passive Film Testing: Use copper sulfate test (ASTM A380) to detect free iron or ferroxyl test to identify areas with inadequate passivation.

- Coastal Installation Maintenance: Monthly freshwater rinse to remove salt accumulation prevents chloride buildup that can overwhelm passive film.

Real-World Performance: Case Studies

For more detailed information on environmental grading, refer to our guide on corrosion resistance grade and design lifespan of metal parts.

Case Study 1: Food Processing Facility (304 Stainless Steel)

Application: Electrical control enclosures in dairy processing plant with daily high-pressure washdown using chlorinated alkaline cleaners at 60°C.

Performance Results: 15 years of continuous operation with no corrosion. The combination of 18% chromium content and electropolished surface prevented bacterial adhesion and maintained the passive film.

Case Study 2: Coastal Substation (316 Stainless Steel)

Application: Outdoor electrical distribution enclosures at coastal substation 800 meters from ocean.

Performance Results: 12 years operation with minimal maintenance. Molybdenum in 316 grade provided critical resistance to chloride pitting, with only minor surface staining observed on horizontal surfaces.

Case Study 3: Chemical Processing Plant (316L Stainless Steel)

Application: Junction boxes and control enclosures in sulfuric acid storage area.

Performance Results: 10 years operation in highly aggressive environment. High nickel content in 316L provided protection in reducing acid environment where chromium oxide alone would be insufficient.

Comparing Stainless Steel to Alternative Enclosure Materials

For a comprehensive guide on selecting materials, please visit our electrical enclosure material selection guide.

Stainless Steel vs. Aluminum

| Property | Stainless Steel 316 | Aluminum 5052 | Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Corrosion mechanism | Chromium oxide passivation | Aluminum oxide layer | Tie (both passive) |

| Chloride resistance | Excellent (with Mo) | Good (requires coating) | Stainless steel |

| Acid resistance | Excellent | Poor to moderate | Stainless steel |

| Alkali resistance | Excellent | Poor | Stainless steel |

| Weight | 8.0 g/cm³ | 2.68 g/cm³ | Aluminum (66% lighter) |

| Mechanical strength | 485-690 MPa | 193-290 MPa | Stainless steel |

| Thermal conductivity | 16.3 W/m·K | 138 W/m·K | Aluminum (heat dissipation) |

| Cost | High | Moderate | Aluminum |

| Service life (coastal) | 25-35 years | 25-35 years (coated) | Tie |

For further comparison details, check our article on stainless steel vs aluminum junction box corrosion resistance.

Selection Guidance: Choose stainless steel for chemical resistance, mechanical strength, and food-grade applications. Choose aluminum for weight-sensitive installations, heat dissipation requirements, and cost optimization in moderate environments.

Stainless Steel vs. Powder-Coated Carbon Steel

| Property | Stainless Steel 304 | Powder-Coated Carbon Steel | Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Corrosion protection | Intrinsic (passive film) | Extrinsic (coating barrier) | Stainless steel |

| Coating damage response | Self-healing | Progressive failure | Stainless steel |

| Maintenance | Minimal | Periodic recoating | Stainless steel |

| Initial cost | High | Low | Carbon steel |

| Lifecycle cost (harsh) | Lower | Higher | Stainless steel |

Selection Guidance: Powder-coated carbon steel is cost-effective for indoor controlled environments with minimal corrosion risk. Stainless steel is superior for outdoor, coastal, chemical, or food-grade applications where coating damage would lead to rapid corrosion.

Practical Recommendations for Specifying Stainless Steel Enclosures

Environmental Assessment Checklist

Before specifying enclosure material, systematically evaluate:

Atmospheric Conditions:

- Distance from coastline (if applicable)

- Chloride deposition rate (ppm)

- Industrial pollutants (SO₂, NOₓ)

- Humidity range and condensation frequency

- Temperature extremes and cycling

Chemical Exposure:

- Acids (type, concentration, temperature)

- Alkalis (type, concentration)

- Organic solvents

- Cleaning chemicals and frequency

- Potential for chemical condensation

Grade Selection Guidelines

Choose 304 when:

- Indoor or sheltered outdoor installation

- Chloride exposure <100 ppm

- No direct acid/alkali contact

- Cost optimization is important

- Food-grade or pharmaceutical application (non-marine)

Choose 316 when:

- Coastal location (<5 km from ocean)

- Chloride exposure >100 ppm

- Chemical processing environment

- Marine or offshore application

- De-icing salt exposure

- Maximum service life is priority

Finish Selection Impact on Passivation

- #4 Brushed Finish: Good corrosion resistance, hides scratches, suitable for most industrial applications.

- #2B Mill Finish: Smooth, excellent corrosion resistance, lowest cost, adequate for non-aesthetic applications.

- Electropolished: Ultra-smooth, superior corrosion resistance, easiest to clean, required for pharmaceutical applications.

- Passivated: Chemical treatment to remove free iron and optimize passive film formation; recommended for all fabricated enclosures.

Common Misconceptions About Stainless Steel Corrosion

Myth 1: “Stainless Steel Never Rusts”

Reality: Stainless steel can corrode under specific conditions such as chloride pitting, crevice corrosion in stagnant zones, stress corrosion cracking at high temperatures, or galvanic corrosion when coupled with noble metals. Proper selection and maintenance prevent these failures.

Myth 2: “Higher Chromium Content Always Means Better Corrosion Resistance”

Reality: While essential, excessive chromium (>20%) can reduce toughness. The optimal range is 16-18%, with molybdenum addition (2-3%) providing more effective chloride resistance than simply increasing chromium.

Myth 3: “Stainless Steel Doesn’t Need Maintenance”

Reality: Periodic cleaning and inspection optimize performance by removing contaminants and allowing early detection of issues. A well-maintained enclosure can last 30-40 years.

Myth 4: “All Stainless Steel Grades Are Food-Safe”

Reality: Certification requires specific finishes (electropolished or #4), proper passivation, and compliance with standards (FDA, 3-A). Ferritic grades are generally not food-grade.

Key Takeaways

- Passivation is a kinetic mechanism: Active metals are protected by a self-forming, self-healing chromium oxide barrier.

- Chromium is essential: Minimum 12% Cr is required; the oxide film is ultra-thin (1-5 nm), dense, and adherent.

- Nickel extends protection: It protects in reducing environments and stabilizes the austenitic structure.

- 304 vs. 316: 316 contains molybdenum for superior chloride resistance, essential for coastal/marine use.

- Manufacturing impacts: Fabrication can damage the film; passivation treatments restore it.

- Maintenance matters: Regular cleaning and inspection ensure decades of service life.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: How long does the passive film take to form after surface damage?

In air at room temperature, the film reaches 80-90% of its full protective capacity within 24 hours and fully stabilizes within 48 hours.

Q2: Can I use 304 stainless steel in coastal environments?

For direct coastal exposure (<1 km from ocean), 316 grade is strongly recommended. 304 may be used in light coastal exposure with frequent maintenance but is prone to pitting.

Q3: What causes “tea staining” on stainless steel, and is it harmful?

Tea staining is superficial discoloration from external iron contamination. It doesn’t compromise structural integrity but should be cleaned to prevent localized corrosion.

Q4: How does welding affect the passive film?

Welding heat can cause sensitization and oxide formation. Using low-carbon grades (L-series) and post-weld passivation restores corrosion resistance.

Q5: Is electropolishing worth the additional cost?

It is justified for pharmaceutical/food-grade cleanability, maximum corrosion resistance in aggressive environments, or aesthetic requirements.

Q6: Can stainless steel enclosures be repaired if damaged?

Yes. Mechanical damage can be polished out, and the passive film will naturally reform. Corrosion damage can be ground out and chemically re-passivated.

Conclusion: Engineering Corrosion Resistance Through Materials Science

The remarkable corrosion resistance of stainless steel electrical enclosures is not magic—it is the result of precise materials science. By understanding the electrochemical paradox (active metals protected by kinetic barriers), the molecular mechanisms of chromium oxide passivation, and the complementary role of nickel in extending protection, engineers can make informed decisions that optimize enclosure performance, service life, and total cost of ownership.

VIOX Electric manufactures stainless steel electrical enclosures in both 304 and 316 grades, engineered to meet NEMA 4X and IP66/IP67 requirements for harsh industrial environments. Our enclosures feature proper manufacturing passivation, precision-welded construction, and corrosion-resistant hardware to ensure the passive film maintains its protective function throughout decades of service.

For technical assistance selecting the optimal stainless steel grade for your specific environmental conditions, contact VIOX Electric’s engineering team.