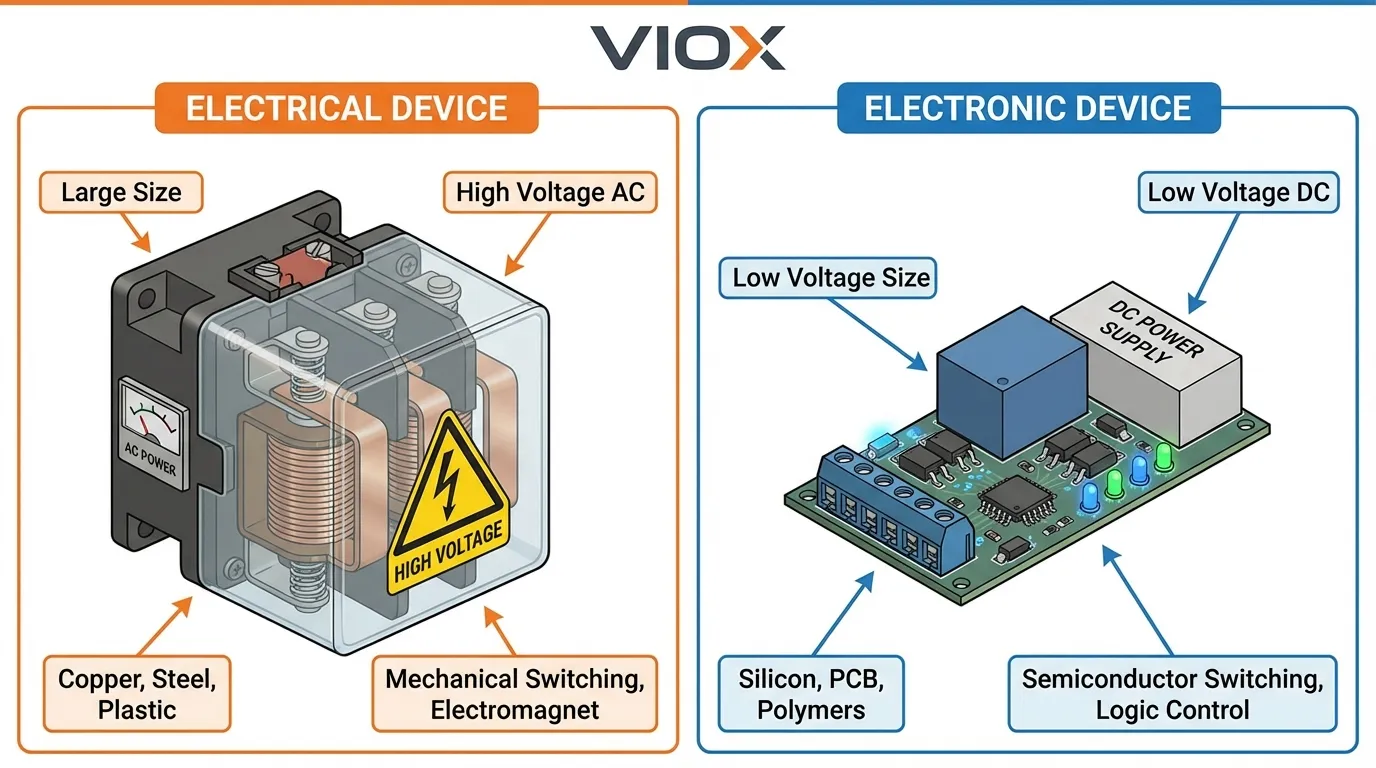

ອຸປະກອນໄຟຟ້າປ່ຽນພະລັງງານໄຟຟ້າເປັນຮູບແບບອື່ນໆ ເຊັ່ນ: ຄວາມຮ້ອນ, ແສງສະຫວ່າງ, ຫຼື ການເຄື່ອນທີ່ ຜ່ານການປ່ຽນແປງພະລັງງານແບບງ່າຍໆ, ໃນຂະນະທີ່ອຸປະກອນເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກໃຊ້ semiconductor ເພື່ອຄວບຄຸມ ແລະ ຈັດການກະແສໄຟຟ້າສໍາລັບວຽກງານທີ່ສັບສົນ ເຊັ່ນ: ການປະມວນຜົນສັນຍານ, ການຂະຫຍາຍສັນຍານ, ແລະ ການຈັດການຂໍ້ມູນ. ຄວາມແຕກຕ່າງທີ່ສໍາຄັນແມ່ນຢູ່ໃນຄວາມສັບສົນຂອງການດໍາເນີນງານ: ອຸປະກອນໄຟຟ້າປະຕິບັດການປ່ຽນພະລັງງານແບບກົງໄປກົງມາ, ໃນຂະນະທີ່ອຸປະກອນເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກຄວບຄຸມການໄຫຼຂອງເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກຢ່າງສະຫຼາດ ເພື່ອປະຕິບັດຫນ້າທີ່ຊັບຊ້ອນ.

Key Takeaways

- ອຸປະກອນໄຟຟ້າ ປ່ຽນພະລັງງານໄຟຟ້າເປັນວຽກງານກົນຈັກ, ຄວາມຮ້ອນ, ຫຼື ແສງສະຫວ່າງ ໂດຍໃຊ້ອຸປະກອນການນໍາໄຟຟ້າ ເຊັ່ນ: ທອງແດງ ແລະ ອາລູມິນຽມ, ດໍາເນີນງານຕົ້ນຕໍດ້ວຍໄຟຟ້າ AC ແຮງດັນສູງ

- ອຸປະກອນເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກ ຄວບຄຸມການໄຫຼຂອງເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກ ໂດຍໃຊ້ອົງປະກອບ semiconductor (ຊິລິຄອນ, ເຈີແມນຽມ) ເພື່ອປະມວນຜົນຂໍ້ມູນ ແລະ ປະຕິບັດວຽກງານທີ່ສັບສົນດ້ວຍແຮງດັນໄຟຟ້າຕ່ໍາກວ່າ

- ອຸປະກອນໄຟຟ້າໂດຍທົ່ວໄປບໍລິໂພກພະລັງງານຫຼາຍກວ່າ ແລະ ມີຂະຫນາດໃຫຍ່ກວ່າ, ໃນຂະນະທີ່ອຸປະກອນເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກມີຂະຫນາດກະທັດຮັດ, ປະຫຍັດພະລັງງານ, ແລະ ສາມາດຈັດການສັນຍານໄດ້

- ຂໍ້ຄວນພິຈາລະນາດ້ານຄວາມປອດໄພແຕກຕ່າງກັນຢ່າງຫຼວງຫຼາຍ: ອຸປະກອນໄຟຟ້າມີຄວາມສ່ຽງຕໍ່ການຖືກໄຟຊອດສູງກວ່າເນື່ອງຈາກແຮງດັນໄຟຟ້າສູງ, ໃນຂະນະທີ່ອຸປະກອນເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກມີຄວາມອ່ອນໄຫວຕໍ່ການໄຫຼຂອງໄຟຟ້າສະຖິດຫຼາຍກວ່າ

- ລະບົບທີ່ທັນສະໄຫມນັບມື້ນັບລວມເອົາທັງສອງເຕັກໂນໂລຢີ, ໂດຍມີການຄວບຄຸມເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກຄຸ້ມຄອງການສົ່ງພະລັງງານໄຟຟ້າໃນການນໍາໃຊ້ແບບປະສົມປະສານ

ເຂົ້າໃຈອຸປະກອນໄຟຟ້າ: ການປ່ຽນພະລັງງານໃນການປະຕິບັດ

ອຸປະກອນໄຟຟ້າເປັນຕົວແທນຂອງພື້ນຖານຂອງການແຈກຢາຍພະລັງງານ ແລະ ການປ່ຽນພະລັງງານໃນການນໍາໃຊ້ທາງອຸດສາຫະກໍາ ແລະ ທີ່ຢູ່ອາໄສ. ອຸປະກອນເຫຼົ່ານີ້ດໍາເນີນງານຕາມຫຼັກການທີ່ກົງໄປກົງມາ: ພວກເຂົາໄດ້ຮັບພະລັງງານໄຟຟ້າ ແລະ ປ່ຽນມັນໂດຍກົງເປັນພະລັງງານຮູບແບບອື່ນ ໂດຍບໍ່ມີການປະມວນຜົນສັນຍານທີ່ສັບສົນ ຫຼື ຕรรกะການຄວບຄຸມ.

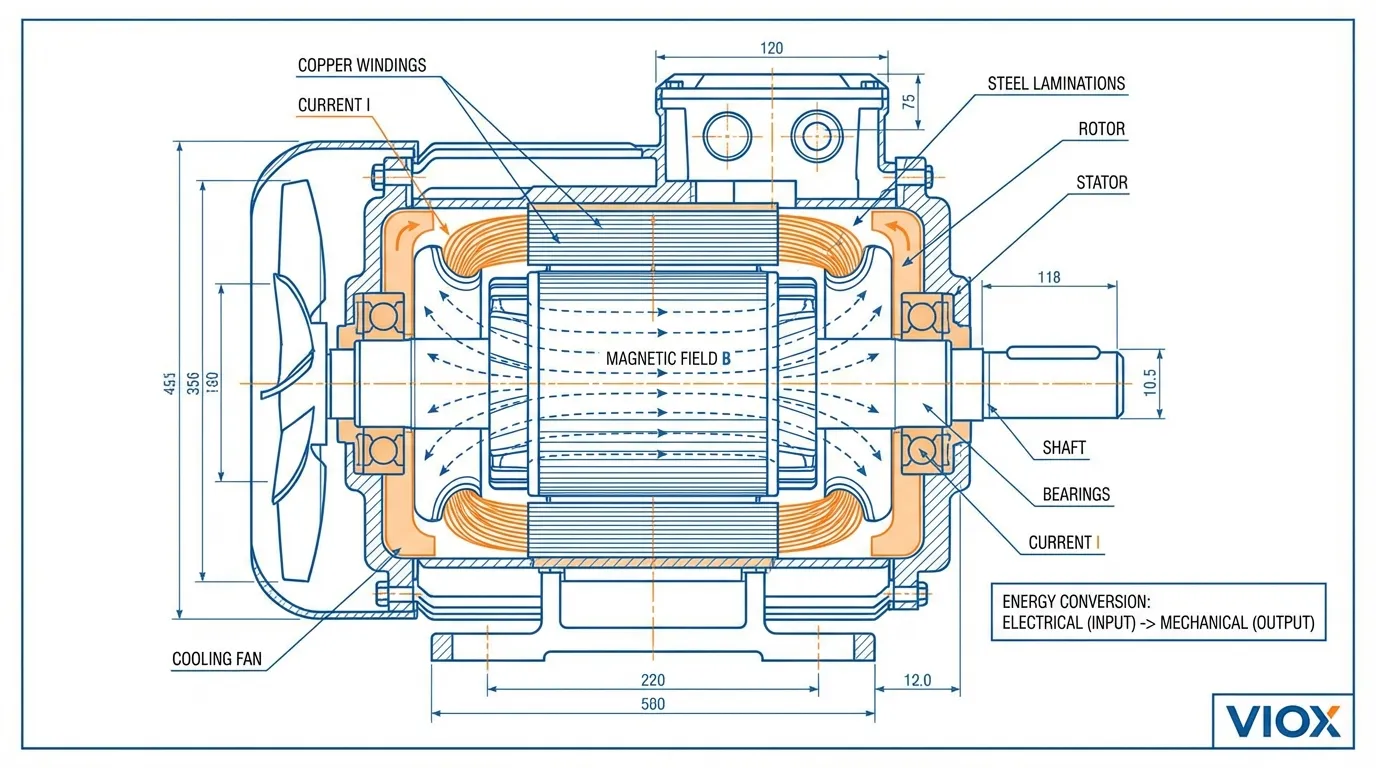

ຄຸນລັກສະນະຫຼັກຂອງອຸປະກອນໄຟຟ້າແມ່ນຢູ່ໃນການກໍ່ສ້າງ ແລະ ວັດສະດຸຂອງພວກມັນ. ພວກເຂົາສ່ວນໃຫຍ່ໃຊ້ອາໂລຫະນໍາໄຟຟ້າ ເຊັ່ນ: ທອງແດງ, ອາລູມິນຽມ, ແລະ ເຫຼັກ ເພື່ອບັນທຸກກະແສໄຟຟ້າສູງຢ່າງມີປະສິດທິພາບ. ເມື່ອທ່ານກວດສອບ ມໍເຕີໄຟຟ້າ, ຕົວຢ່າງ, ທ່ານຈະພົບເຫັນການມ້ວນທອງແດງຫນັກ ແລະ ແຜ່ນເຫຼັກທີ່ຖືກອອກແບບມາເພື່ອຮອງຮັບການໂຫຼດພະລັງງານຢ່າງຫຼວງຫຼາຍ. ອຸປະກອນເຫຼົ່ານີ້ໂດຍທົ່ວໄປດໍາເນີນງານດ້ວຍກະແສໄຟຟ້າສະຫຼັບ (AC) ທີ່ແຮງດັນໄຟຟ້າເສັ້ນມາດຕະຖານ—120V, 240V, ຫຼື ສູງກວ່າໃນສະພາບແວດລ້ອມອຸດສາຫະກໍາ.

ອຸປະກອນໄຟຟ້າເກັ່ງໃນວຽກງານກົນຈັກ ແລະ ການປ່ຽນພະລັງງານ. ກ ໝໍ້ແປງໄຟຟ້າ ປ່ຽນລະດັບແຮງດັນໄຟຟ້າຜ່ານການเหนี่ยวนําໄຟຟ້າ, ໃນຂະນະທີ່ເຄື່ອງເຮັດຄວາມຮ້ອນໄຟຟ້າປ່ຽນພະລັງງານໄຟຟ້າເປັນພະລັງງານຄວາມຮ້ອນຜ່ານຄວາມຮ້ອນ resistive. ຄວາມລຽບງ່າຍຂອງການດໍາເນີນງານຂອງພວກເຂົາເຮັດໃຫ້ພວກເຂົາແຂງແຮງ ແລະ ເຊື່ອຖືໄດ້ສໍາລັບການນໍາໃຊ້ພະລັງງານສູງ, ເຖິງແມ່ນວ່າພວກເຂົາຂາດຄວາມສາມາດໃນການຄວບຄຸມທີ່ຊັບຊ້ອນຂອງຄູ່ຮ່ວມງານເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກຂອງພວກເຂົາ.

ຄຸນລັກສະນະທາງກາຍະພາບຂອງອຸປະກອນໄຟຟ້າສະທ້ອນໃຫ້ເຫັນເຖິງຄວາມຕ້ອງການໃນການຈັດການພະລັງງານຂອງພວກເຂົາ. ພວກເຂົາມັກຈະມີຂະຫນາດໃຫຍ່ກວ່າ ແລະ ຫນັກກວ່າເນື່ອງຈາກຕົວນໍາທີ່ສໍາຄັນ ແລະ ແກນແມ່ເຫຼັກທີ່ຈໍາເປັນສໍາລັບການຖ່າຍທອດພະລັງງານທີ່ມີປະສິດທິພາບ. ກ ວົງຈອນໄຟ ຫຼື 塑壳断路器 ປົກປ້ອງວົງຈອນໄຟຟ້າຕ້ອງມີຂະຫນາດເພື່ອຂັດຂວາງກະແສໄຟຟ້າຜິດປົກກະຕິທີ່ສາມາດບັນລຸໄດ້ຫລາຍພັນແອມແປຣ໌—ຫນ້າທີ່ກົນຈັກ ແລະ ໄຟຟ້າລ້ວນໆທີ່ຕ້ອງການການກໍ່ສ້າງທີ່ແຂງແຮງ.

ອຸປະກອນເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກ: ຄວາມສະຫຼາດທີ່ຢູ່ເບື້ອງຫຼັງເຕັກໂນໂລຢີທີ່ທັນສະໄຫມ

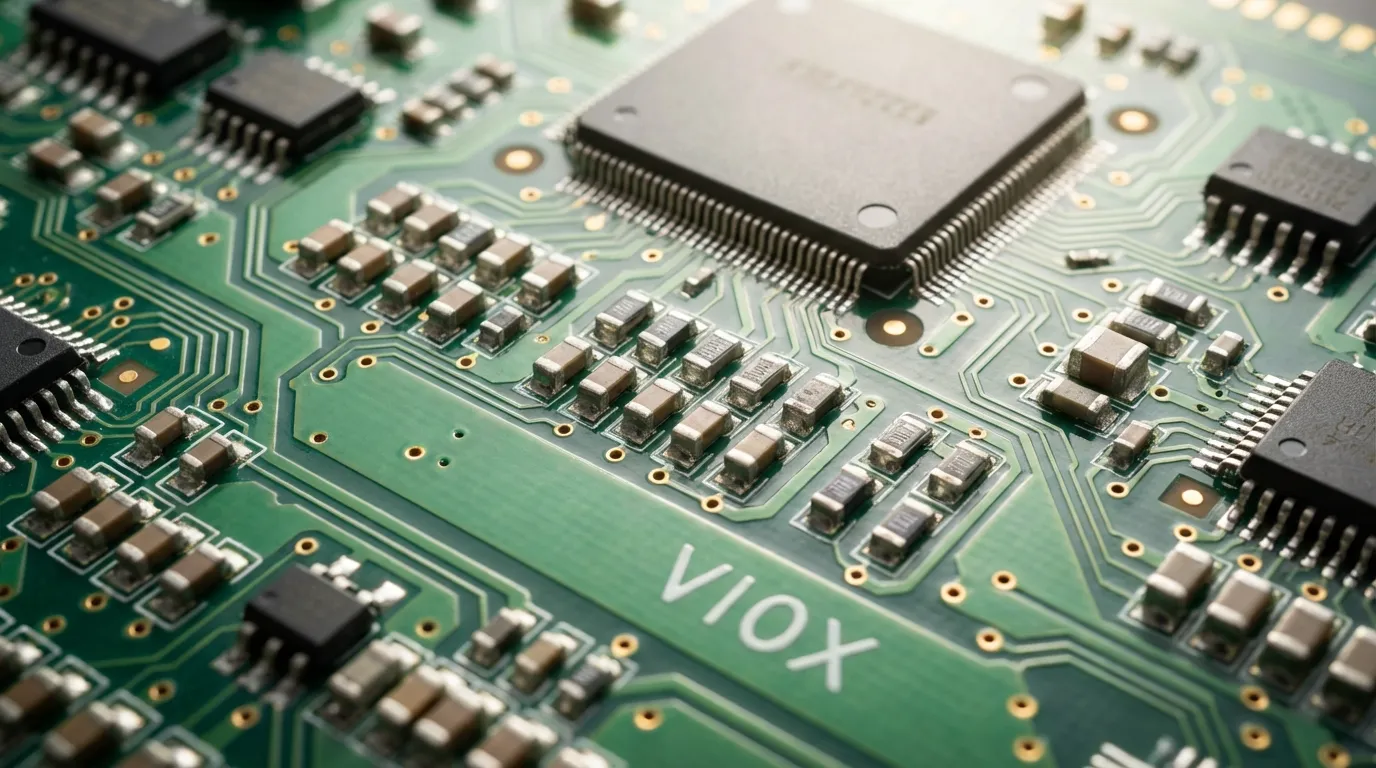

ອຸປະກອນເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກເປັນຕົວແທນຂອງການປ່ຽນແປງແບບຢ່າງຈາກການປ່ຽນພະລັງງານແບບງ່າຍໆໄປສູ່ການຄວບຄຸມກະແສໄຟຟ້າທີ່ສະຫຼາດ ແລະ ການປະມວນຜົນຂໍ້ມູນ. ຫົວໃຈຂອງພວກເຂົາແມ່ນເຕັກໂນໂລຢີ semiconductor—ວັດສະດຸເຊັ່ນ: ຊິລິຄອນ ແລະ ເຈີແມນຽມທີ່ສາມາດຖືກອອກແບບຢ່າງຊັດເຈນເພື່ອຄວບຄຸມການໄຫຼຂອງເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກໃນລະດັບປະລໍາມະນູ.

ອົງປະກອບພື້ນຖານຂອງອຸປະກອນເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກແມ່ນ transistor, ອົງປະກອບ semiconductor ທີ່ສາມາດຂະຫຍາຍສັນຍານ ຫຼື ເຮັດຫນ້າທີ່ເປັນສະວິດເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກ. ທັນສະໄຫມ ວົງຈອນປະສົມປະສານ ບັນຈຸ transistors ຫລາຍພັນລ້ານໂຕທີ່ເຮັດວຽກຮ່ວມກັນເພື່ອປະມວນຜົນຂໍ້ມູນ, ປະຕິບັດຄໍາແນະນໍາ, ແລະ ຈັດການການດໍາເນີນງານທີ່ສັບສົນ. ການເຮັດໃຫ້ມີຂະຫນາດນ້ອຍນີ້ຊ່ວຍໃຫ້ອຸປະກອນກະທັດຮັດ, ມີອໍານາດທີ່ພວກເຮົາອີງໃສ່ປະຈໍາວັນ—ຈາກໂທລະສັບສະຫຼາດໄປຫາຕົວຄວບຄຸມອຸດສາຫະກໍາ.

ອຸປະກອນເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກດໍາເນີນງານຕົ້ນຕໍດ້ວຍກະແສໄຟຟ້າໂດຍກົງ (DC) ທີ່ແຮງດັນໄຟຟ້າຕ່ໍາຂ້ອນຂ້າງ, ໂດຍທົ່ວໄປຕັ້ງແຕ່ 1.8V ຫາ 48V. ການດໍາເນີນງານແຮງດັນໄຟຟ້າຕ່ໍານີ້ປະກອບສ່ວນເຂົ້າໃນປະສິດທິພາບພະລັງງານ ແລະ ໂປຣໄຟລ໌ຄວາມປອດໄພຂອງພວກເຂົາ. ເມື່ອອຸປະກອນເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກຕ້ອງການໂຕ້ຕອບກັບລະບົບພະລັງງານ AC, ມັນປະກອບມີວົງຈອນການປ່ຽນພະລັງງານເພື່ອປ່ຽນ ແລະ ຄວບຄຸມແຮງດັນໄຟຟ້າຢ່າງເຫມາະສົມ.

ຄວາມສາມາດໃນການຈັດການສັນຍານໄຟຟ້າຈໍາແນກອຸປະກອນເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກຈາກອຸປະກອນໄຟຟ້າ. ເຄື່ອງຂະຫຍາຍສັນຍານເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກສາມາດເອົາສັນຍານທີ່ອ່ອນແອຈາກໄມໂຄຣໂຟນ ແລະ ເພີ່ມມັນເພື່ອຂັບລໍາໂພງ. ໄມໂຄຣຄອນໂທລເລີສາມາດອ່ານຂໍ້ມູນປ້ອນເຂົ້າຂອງເຊັນເຊີ, ປະຕິບັດຕรรกะທີ່ຕັ້ງໂປຣແກຣມ, ແລະ ຄວບຄຸມຜົນຜະລິດ—ທັງຫມົດໃນຂະນະທີ່ບໍລິໂພກພະລັງງານຫນ້ອຍທີ່ສຸດ. ຄວາມສາມາດໃນການປະມວນຜົນສັນຍານນີ້ຊ່ວຍໃຫ້ທຸກສິ່ງທຸກຢ່າງຈາກ ອຸປະກອນປ້ອງກັນກະແສໄຟຟ້າ ດ້ວຍການຕິດຕາມກວດກາເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກໄປຫາທີ່ຊັບຊ້ອນ ໂມດູນ relay ທີ່ໂຕ້ຕອບລະຫວ່າງລະບົບຄວບຄຸມ ແລະ ວົງຈອນພະລັງງານ.

ການວິເຄາະປຽບທຽບ: ຄວາມແຕກຕ່າງທີ່ສໍາຄັນທີ່ສໍາຄັນ

| ລັກສະນະ | ອຸປະກອນໄຟຟ້າ | ອຸປະກອນເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກ |

|---|---|---|

| ຟັງຊັນປະຖົມ | ການປ່ຽນພະລັງງານ (ໄຟຟ້າເປັນກົນຈັກ, ຄວາມຮ້ອນ, ຫຼື ແສງສະຫວ່າງ) | ການປະມວນຜົນສັນຍານ, ການຄວບຄຸມ, ແລະ ການຈັດການຂໍ້ມູນ |

| ວັດສະດຸຫຼັກ | ທອງແດງ, ອາລູມິນຽມ, ເຫຼັກ (ຕົວນໍາ) | ຊິລິຄອນ, ເຈີແມນຽມ (semiconductors) |

| ແຮງດັນປະຕິບັດງານ | ແຮງດັນໄຟຟ້າສູງ (120V-480V AC ປົກກະຕິ) | ແຮງດັນໄຟຟ້າຕ່ໍາ (1.8V-48V DC ປົກກະຕິ) |

| ປະເພດກະແສ | ສ່ວນໃຫຍ່ແມ່ນ AC (ກະແສໄຟຟ້າສະຫຼັບ) | ສ່ວນໃຫຍ່ແມ່ນ DC (ກະແສໄຟຟ້າໂດຍກົງ) |

| ການບໍລິໂພກພະລັງງານ | ສູງ (ກິໂລວັດຫາເມກາວັດ) | ຕ່ໍາ (ມິນລິວັດຫາວັດ) |

| ດ້ານຮ່າງກາຍຂະຫນາດ | ໃຫຍ່ ແລະ ຫນັກ | ກະທັດຮັດ ແລະ ນ້ຳໜັກເບົາ |

| ເວລາຕອບສະຫນອງ | ຊ້າກວ່າ (ກົນຈັກ/ໄຟຟ້າ) | ໄວ (ນາໂນວິນາທີຫາໄມໂຄຣວິນາທີ) |

| ຄວາມສັບສົນ | ການດໍາເນີນງານແບບງ່າຍດາຍ, ໂດຍກົງ | ຕรรกะທີ່ສັບສົນ, ຕັ້ງໂປຣແກຣມໄດ້ |

| ຕົວຢ່າງ | ມໍເຕີ, ຫມໍ້ແປງໄຟຟ້າ, ເຄື່ອງເຮັດຄວາມຮ້ອນ, contactors | ໄມໂຄຣໂປຣເຊສເຊີ, transistors, ເຊັນເຊີ, ເຄື່ອງຂະຫຍາຍສັນຍານ |

ຫຼັກການເຮັດວຽກ: ຄວາມແຕກຕ່າງໃນການດໍາເນີນງານພື້ນຖານ

ຫຼັກການດໍາເນີນງານຂອງອຸປະກອນໄຟຟ້າ ແລະ ເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກເປີດເຜີຍວ່າເປັນຫຍັງພວກເຂົາເກັ່ງໃນການນໍາໃຊ້ທີ່ແຕກຕ່າງກັນ. ອຸປະກອນໄຟຟ້າອີງໃສ່ທິດສະດີໄຟຟ້າແບບຄລາສສິກ—ກົດຫມາຍຂອງການเหนี่ยวนําຂອງຟາຣາດີ, ກົດຫມາຍຂອງແອມແປຣ໌, ແລະ ກົດຫມາຍຂອງໂອມຄວບຄຸມພຶດຕິກໍາຂອງພວກເຂົາ. ກ ຄອນແທັກເຕີ AC ໃຊ້ຂົດລວດໄຟຟ້າເພື່ອປິດຫນ້າສໍາຜັດທາງກົນຈັກ, ເຊື່ອມຕໍ່ພະລັງງານໂດຍກົງກັບການໂຫຼດ. ການດໍາເນີນງານແມ່ນ binary ແລະ ກົງໄປກົງມາ: ເປີດໃຊ້ຂົດລວດ, ປິດຫນ້າສໍາຜັດ, ສົ່ງພະລັງງານ.

ອຸປະກອນເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກດໍາເນີນງານຢູ່ໃນຂອບເຂດ quantum ຂອງຟີຊິກ semiconductor. ພຶດຕິກໍາຂອງເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກໃນຊິລິຄອນ doped ສ້າງ P-N junctions ທີ່ປະກອບເປັນພື້ນຖານຂອງ diodes, transistors, ແລະ ວົງຈອນປະສົມປະສານທີ່ສັບສົນ. ກ relay solid-state ໃຊ້ສະວິດ semiconductor (ໂດຍທົ່ວໄປແມ່ນ MOSFETs ຫຼື IGBTs) ເພື່ອຄວບຄຸມການໄຫຼຂອງກະແສໄຟຟ້າໂດຍບໍ່ມີຫນ້າສໍາຜັດທາງກົນຈັກ, ເຮັດໃຫ້ການດໍາເນີນງານງຽບ, ອາຍຸຍືນກວ່າ, ແລະ ຄວາມໄວໃນການປ່ຽນໄວຂຶ້ນ. ການຄວບຄຸມແມ່ນຊັດເຈນ ແລະ ສາມາດຖືກປັບປ່ຽນໄດ້—ບໍ່ພຽງແຕ່ເປີດ ຫຼື ປິດ, ແຕ່ລະດັບການນໍາທີ່ແຕກຕ່າງກັນ.

ວິທະຍາສາດວັດສະດຸ ແລະ ການກໍ່ສ້າງ

ວັດສະດຸທີ່ໃຊ້ໃນອຸປະກອນໄຟຟ້າທຽບກັບເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກມີຜົນກະທົບໂດຍກົງຕໍ່ຄຸນລັກສະນະການປະຕິບັດ ແລະ ຄວາມເຫມາະສົມຂອງການນໍາໃຊ້ຂອງພວກເຂົາ. ອຸປະກອນໄຟຟ້າໃຊ້ອຸປະກອນທີ່ເລືອກສໍາລັບການນໍາໄຟຟ້າສູງ ແລະ ຄວາມແຂງແຮງທາງກົນຈັກ. busbars ທອງແດງ ໃນແຜງແຈກຢາຍບັນທຸກຫລາຍຮ້ອຍແອມແປຣ໌ທີ່ມີແຮງດັນໄຟຟ້າຫຼຸດລົງຫນ້ອຍທີ່ສຸດ. Cable lugs ແລະ terminals ຕ້ອງທົນທານຕໍ່ຄວາມກົດດັນທາງກົນຈັກໃນຂະນະທີ່ຮັກສາການເຊື່ອມຕໍ່ຄວາມຕ້ານທານຕ່ໍາ.

ອຸປະກອນເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກຕ້ອງການວັດສະດຸທີ່ມີຄຸນສົມບັດໄຟຟ້າທີ່ຄວບຄຸມຢ່າງຊັດເຈນ. ການຜະລິດ semiconductor ກ່ຽວຂ້ອງກັບການ doping ຊິລິຄອນບໍລິສຸດທີ່ມີປະລິມານຫນ້ອຍຂອງອົງປະກອບເຊັ່ນ: boron ຫຼື phosphorus ເພື່ອສ້າງພາກພື້ນທີ່ມີຄຸນລັກສະນະໄຟຟ້າສະເພາະ. ຄວາມຕ້ອງການຄວາມບໍລິສຸດແມ່ນສູງສຸດ—ຊິລິຄອນຊັ້ນ semiconductor ທີ່ທັນສະໄຫມຕ້ອງມີຄວາມບໍລິສຸດ 99.9999999% (ເກົ້າເກົ້າ). ລະດັບການຄວບຄຸມວັດສະດຸນີ້ຊ່ວຍໃຫ້ພຶດຕິກໍາທີ່ຄາດເດົາໄດ້ທີ່ຈໍາເປັນສໍາລັບຕรรกะດິຈິຕອນ ແລະ ການປະມວນຜົນສັນຍານ analog.

ຂໍ້ຄວນພິຈາລະນາກ່ຽວກັບຄວາມປອດໄພ ແລະ ໂປຣໄຟລ໌ຄວາມສ່ຽງ

ຂໍ້ຄວນພິຈາລະນາກ່ຽວກັບຄວາມປອດໄພແຕກຕ່າງກັນຢ່າງຫຼວງຫຼາຍລະຫວ່າງອຸປະກອນໄຟຟ້າ ແລະ ເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກເນື່ອງຈາກລະດັບແຮງດັນໄຟຟ້າ ແລະ ຮູບແບບຄວາມລົ້ມເຫຼວຂອງມັນ. ອຸປະກອນໄຟຟ້າທີ່ເຮັດວຽກຢູ່ແຮງດັນໄຟຟ້າສາຍສົ່ງມີຄວາມສ່ຽງຕໍ່ການຖືກໄຟຊັອດຢ່າງຫຼວງຫຼາຍ. ຄວາມຜິດປົກກະຕິໃນ ແຜງວົງຈອນຕັດໄຟ ຫຼື ກະດານແຈກຢາຍ ສາມາດເຮັດໃຫ້ບຸກຄະລາກອນໄດ້ຮັບແຮງດັນໄຟຟ້າທີ່ເປັນອັນຕະລາຍເຖິງຊີວິດ. ເຫດການໄຟຟ້າລັດວົງຈອນໃນອຸປະກອນໄຟຟ້າສາມາດປ່ອຍພະລັງງານມະຫາສານ, ເຊິ່ງກໍ່ໃຫ້ເກີດການບາດແຜ ແລະ ບາດເຈັບສາຫັດ. ຂັ້ນຕອນຄວາມປອດໄພໄຟຟ້າ ແລະ ອຸປະກອນປ້ອງກັນແມ່ນມີຄວາມຈຳເປັນເມື່ອເຮັດວຽກກັບອຸປະກອນໄຟຟ້າ.

ອຸປະກອນເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກ, ທີ່ເຮັດວຽກຢູ່ແຮງດັນໄຟຟ້າຕ່ຳ, ມີຄວາມສ່ຽງຕໍ່ການຖືກໄຟຊັອດໜ້ອຍທີ່ສຸດຕໍ່ບຸກຄະລາກອນ. ຢ່າງໃດກໍຕາມ, ພວກມັນມີຄວາມສ່ຽງຕໍ່ໄພຂົ່ມຂູ່ທີ່ແຕກຕ່າງກັນ. ໄຟຟ້າສະຖິດທີ່ບໍ່ສາມາດຮັບຮູ້ໄດ້ຕໍ່ຄົນສາມາດທຳລາຍຈຸດເຊື່ອມຕໍ່ຂອງ semiconductor ທີ່ລະອຽດອ່ອນໄດ້. ການປ້ອງກັນໄຟຟ້າ ກາຍເປັນສິ່ງທີ່ສຳຄັນເພື່ອປົກປ້ອງວົງຈອນເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກຈາກແຮງດັນໄຟຟ້າຊົ່ວຄາວ. ອຸປະກອນເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກຍັງສ້າງ ແລະ ຮັບຜົນກະທົບຈາກການລົບກວນທາງແມ່ເຫຼັກໄຟຟ້າ (EMI), ເຊິ່ງຮຽກຮ້ອງໃຫ້ມີການອອກແບບ ແລະ ການປ້ອງກັນຢ່າງລະມັດລະວັງໃນສະພາບແວດລ້ອມອຸດສາຫະກຳ.

ການນຳໃຊ້ໃນໂລກຕົວຈິງ ແລະ ການເຊື່ອມໂຍງລະບົບ

ຄໍາຮ້ອງສະຫມັກອຸດສາຫະກໍາແລະການຄ້າ

ໃນສະພາບແວດລ້ອມອຸດສາຫະກຳ, ຄວາມແຕກຕ່າງລະຫວ່າງອຸປະກອນໄຟຟ້າ ແລະ ເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກກາຍເປັນສິ່ງທີ່ສຳຄັນໃນທາງປະຕິບັດ. ລະບົບຄວບຄຸມມໍເຕີສະແດງໃຫ້ເຫັນເຖິງການເຊື່ອມໂຍງນີ້ຢ່າງສົມບູນ. ຕົວເລີ່ມມໍເຕີ (motor starter) ຕົວມັນເອງເປັນອຸປະກອນໄຟຟ້າ—ເຄື່ອງສຳຜັດໜັກ, thermal overload relays, ແລະ ສາຍໄຟຟ້າຈັດການກັບກະແສໄຟຟ້າສູງທີ່ຈຳເປັນເພື່ອຂັບເຄື່ອນມໍເຕີອຸດສາຫະກຳ. ຢ່າງໃດກໍຕາມ, ຕรรกะການຄວບຄຸມທີ່ກຳນົດເວລາທີ່ຈະເລີ່ມຕົ້ນ, ຢຸດ, ຫຼື ປົກປ້ອງມໍເຕີແມ່ນອີງໃສ່ອຸປະກອນເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກຫຼາຍຂຶ້ນ—ຕົວຄວບຄຸມຕรรกะທີ່ສາມາດຕັ້ງໂປຣແກຣມໄດ້ (PLCs), ໄດຣຟ໌ຄວາມຖີ່ປ່ຽນແປງໄດ້ (VFDs), ແລະ ເຊັນເຊີເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກ.

ທັນສະໄຫມ switchgear ສະແດງໃຫ້ເຫັນເຖິງວິທີການປະສົມປະສານນີ້. ໜ້າທີ່ການຂັດຂວາງພະລັງງານຍັງຄົງເປັນໄຟຟ້າໂດຍພື້ນຖານ—ໜ້າສຳຜັດກົນຈັກຕ້ອງແຍກອອກຈາກກັນທາງກາຍະພາບເພື່ອທຳລາຍກະແສໄຟຟ້າຜິດປົກກະຕິສູງ. ແຕ່ໜ່ວຍເດີນທາງເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກຕິດຕາມກວດກາປະຈຸບັນ, ແຮງດັນໄຟຟ້າ, ແລະ ຄຸນນະພາບພະລັງງານ, ເຮັດໃຫ້ການຕັດສິນໃຈທີ່ສະຫຼາດກ່ຽວກັບເວລາທີ່ຈະເດີນທາງ. MCCB ແບບເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກ ລວມຄວາມສາມາດໃນການຂັດຂວາງທີ່ເຂັ້ມແຂງຂອງອຸປະກອນໄຟຟ້າກັບຄວາມແມ່ນຍຳ ແລະ ຄວາມສາມາດໃນການຕັ້ງໂປຣແກຣມຂອງເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກ.

ລະບົບທີ່ຢູ່ອາໄສ ແລະ ອາຄານ

ໃນການນຳໃຊ້ທີ່ຢູ່ອາໄສ, ການລວມຕົວຂອງເຕັກໂນໂລຊີໄຟຟ້າ ແລະ ເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກກຳລັງປ່ຽນແປງວິທີທີ່ອາຄານບໍລິໂພກ ແລະ ຈັດການພະລັງງານ. ອຸປະກອນໄຟຟ້າແບບດັ້ງເດີມເຊັ່ນ: ວົງຈອນໄຟສ່ອງສະຫວ່າງ ແລະ ລະບົບຄວາມຮ້ອນແມ່ນຖືກຄວບຄຸມຫຼາຍຂຶ້ນໂດຍອຸປະກອນເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກ—ເຄື່ອງຄວບຄຸມອຸນຫະພູມອັດສະລິຍະ, ເຊັນເຊີການຄອບຄອງ, ແລະ ສະວິດຈັບເວລາ. ການເຊື່ອມໂຍງນີ້ຊ່ວຍໃຫ້ການເພີ່ມປະສິດທິພາບພະລັງງານທີ່ເປັນໄປບໍ່ໄດ້ກັບລະບົບໄຟຟ້າຢ່າງດຽວ.

ຝາປິດໄຟຟ້າ ແລະ ກ່ອງແຍກ ມີທັງອົງປະກອບການແຈກຢາຍພະລັງງານໄຟຟ້າ ແລະ ອຸປະກອນຄວບຄຸມເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກ. ແຜງໄຟຟ້າທີ່ທັນສະໄໝອາດມີ MCBs ແລະ RCCBs ແບບດັ້ງເດີມຄຽງຄູ່ກັບ ອຸປະກອນປ້ອງກັນແຮງດັນເກີນ ເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກ ແລະ ອຸປະກອນວັດແທກອັດສະລິຍະ. ສິ່ງທ້າທາຍສຳລັບຜູ້ຕິດຕັ້ງ ແລະ ວິສະວະກອນແມ່ນຢູ່ໃນຄວາມເຂົ້າໃຈທັງສອງໂດເມນ ແລະ ການພົວພັນຂອງພວກເຂົາ.

ລະບົບພະລັງງານທົດແທນ

ລະບົບແສງຕາເວັນ photovoltaic ສະແດງໃຫ້ເຫັນເຖິງການຮ່ວມມືທີ່ຈຳເປັນລະຫວ່າງເຕັກໂນໂລຊີໄຟຟ້າ ແລະ ເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກ. ກ່ອງລວມແສງຕາເວັນ ໃຊ້ອົງປະກອບໄຟຟ້າ—ເບຣກເກີວົງຈອນ DC ແລະ ຟິວ—ເພື່ອລວມຜົນຜະລິດສາຍຢ່າງປອດໄພ. ຢ່າງໃດກໍຕາມ, ການຕິດຕາມຈຸດພະລັງງານສູງສຸດ (MPPT) ທີ່ເພີ່ມປະສິດທິພາບການເກັບກ່ຽວພະລັງງານແມ່ນເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກຢ່າງດຽວ, ໂດຍໃຊ້ algorithms ທີ່ຊັບຊ້ອນ ແລະ ເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກພະລັງງານເພື່ອປັບຈຸດປະຕິບັດງານຢ່າງຕໍ່ເນື່ອງ.

ລະບົບເກັບຮັກສາພະລັງງານຫມໍ້ໄຟ ເຊັ່ນດຽວກັນປະສົມປະສານທັງສອງເຕັກໂນໂລຊີ. ຈຸລັງແບັດເຕີຣີເອງແມ່ນອຸປະກອນ electrochemical, ແຕ່ລະບົບການຈັດການແບັດເຕີຣີ (BMS) ທີ່ຕິດຕາມກວດກາແຮງດັນໄຟຟ້າຂອງຈຸລັງ, ຈັດການການສາກໄຟ, ແລະ ຮັບປະກັນຄວາມປອດໄພແມ່ນເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກທັງໝົດ. ການປ່ຽນພະລັງງານລະຫວ່າງແຮງດັນໄຟຟ້າ DC ຂອງແບັດເຕີຣີ ແລະ ແຮງດັນໄຟຟ້າ AC ຂອງຕາຂ່າຍໄຟຟ້າໃຊ້ inverters ເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກ, ໃນຂະນະທີ່ໄຟຟ້າ ເຄື່ອງສຳຜັດ ແລະ ສະວິດຕັດການເຊື່ອມຕໍ່ ໃຫ້ການແຍກທາງກາຍະພາບເພື່ອຄວາມປອດໄພ.

ຂໍ້ຄວນພິຈາລະນາໃນການອອກແບບ ແລະ ເງື່ອນໄຂການຄັດເລືອກ

ເວລາທີ່ຈະລະບຸອຸປະກອນໄຟຟ້າ

ອຸປະກອນໄຟຟ້າຍັງຄົງເປັນທາງເລືອກທີ່ດີທີ່ສຸດສຳລັບການນຳໃຊ້ທີ່ຕ້ອງການການຈັດການພະລັງງານສູງ, ການກໍ່ສ້າງທີ່ເຂັ້ມແຂງ, ແລະ ການດຳເນີນງານທີ່ງ່າຍດາຍ. ເມື່ອທ່ານຕ້ອງການປ່ຽນກິໂລວັດ ຫຼື ເມກາວັດຂອງພະລັງງານ, ໄຟຟ້າ contactors ແລະ ເຄື່ອງຕັດວົງຈອນ ໃຫ້ຄວາມໜ້າເຊື່ອຖືທີ່ພິສູດແລ້ວ. ການດຳເນີນງານກົນຈັກຂອງພວກເຂົາໃຫ້ການຢືນຢັນທີ່ເບິ່ງເຫັນໄດ້ຂອງຕຳແໜ່ງຕິດຕໍ່—ຄຸນສົມບັດຄວາມປອດໄພທີ່ສຳຄັນໃນສະຖານະການບຳລຸງຮັກສາ.

ຂໍ້ຄວນພິຈາລະນາກ່ຽວກັບຄ່າໃຊ້ຈ່າຍມັກຈະເອື້ອອຳນວຍໃຫ້ອຸປະກອນໄຟຟ້າສຳລັບໜ້າທີ່ການແຈກຢາຍພະລັງງານທີ່ກົງໄປກົງມາ. ກົນຈັກ ຣີເລຊັກເວລາ ລາຄາຖືກກວ່າເຄື່ອງຈັບເວລາເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກສຳລັບການນຳໃຊ້ທີ່ງ່າຍດາຍ. ການກໍ່ສ້າງທີ່ທົນທານຂອງອຸປະກອນໄຟຟ້າເຮັດໃຫ້ພວກເຂົາເໝາະສົມກັບສະພາບແວດລ້ອມທີ່ຮຸນແຮງທີ່ອົງປະກອບເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກອາດຈະລົ້ມເຫຼວເນື່ອງຈາກອຸນຫະພູມທີ່ຮຸນແຮງ, ການສັ່ນສະເທືອນ, ຫຼື ການປົນເປື້ອນ.

ເວລາທີ່ອຸປະກອນເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກມີຄວາມຈຳເປັນ

ອຸປະກອນເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກກາຍເປັນສິ່ງຈຳເປັນເມື່ອການນຳໃຊ້ຕ້ອງການການຄວບຄຸມທີ່ຊັດເຈນ, ການປະມວນຜົນສັນຍານ, ຫຼື ຄວາມສາມາດໃນການຕັ້ງໂປຣແກຣມ. Voltage monitoring relays ທີ່ປົກປ້ອງອຸປະກອນຈາກສະພາບແຮງດັນໄຟຟ້າເກີນ/ຕ່ຳຕ້ອງການຄວາມຖືກຕ້ອງ ແລະ ເວລາຕອບສະໜອງທີ່ໄວທີ່ເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກເທົ່ານັ້ນທີ່ສາມາດໃຫ້ໄດ້. ການສື່ສານລະຫວ່າງອຸປະກອນ—ບໍ່ວ່າຈະເປັນ Modbus, Ethernet, ຫຼື ໂປຣໂຕຄໍໄຮ້ສາຍ—ຕ້ອງການການໂຕ້ຕອບເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກ.

ຂໍ້ບັງຄັບປະສິດທິພາບດ້ານພະລັງງານນັບມື້ນັບຫຼາຍຂຶ້ນຂັບເຄື່ອນການຮັບຮອງເອົາອຸປະກອນເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກ. ບາລາດເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກສຳລັບໄຟສ່ອງສະຫວ່າງ, ໄດຣຟ໌ຄວາມຖີ່ປ່ຽນແປງໄດ້ສຳລັບມໍເຕີ, ແລະ ລະບົບການຈັດການພະລັງງານອັດສະລິຍະສາມາດຫຼຸດຜ່ອນການບໍລິໂພກພະລັງງານໄດ້ 20-50% ເມື່ອທຽບກັບວິທີການຄວບຄຸມໄຟຟ້າແບບດັ້ງເດີມ. ຄ່າໃຊ້ຈ່າຍເບື້ອງຕົ້ນຂອງອຸປະກອນເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກມັກຈະໄດ້ຮັບການຊົດເຊີຍຢ່າງໄວວາຜ່ານການປະຫຍັດພະລັງງານ.

ວິທີການບຳລຸງຮັກສາ ແລະ ແກ້ໄຂບັນຫາ

ການບຳລຸງຮັກສາອຸປະກອນໄຟຟ້າ

ການຮັກສາອຸປະກອນໄຟຟ້າມຸ່ງເນັ້ນໃສ່ຄວາມສົມບູນຂອງກົນຈັກ ແລະ ຄວາມຮ້ອນ. ການກວດກາເປັນປົກກະຕິຂອງ ການເຊື່ອມຕໍ່ໄຟຟ້າ ສຳລັບຄວາມແໜ້ນໜາປ້ອງກັນຄວາມຮ້ອນ resistive ແລະ ຄວາມລົ້ມເຫຼວໃນທີ່ສຸດ. ຄວາມຮ້ອນ ກໍານົດຈຸດຮ້ອນກ່ອນທີ່ພວກເຂົາຈະເຮັດໃຫ້ເກີດບັນຫາ. ການສວມໃສ່ກົນຈັກໃນເຄື່ອງສຳຜັດ ແລະ relays ຮຽກຮ້ອງໃຫ້ມີການປ່ຽນແທນໜ້າສຳຜັດ ແລະ ພາກຮຽນ spring ເປັນໄລຍະ.

ການທົດສອບອຸປະກອນໄຟຟ້າໂດຍທົ່ວໄປແລ້ວແມ່ນກ່ຽວຂ້ອງກັບການວັດແທກແຮງດັນໄຟຟ້າ, ກະແສໄຟຟ້າ, ແລະ ຄວາມຕ້ານທານດ້ວຍ multimeters ມາດຕະຖານ. ການທົດສອບວົງຈອນຕັດໄຟ ກວດສອບຄຸນລັກສະນະການເດີນທາງ ແລະ ຄວາມສາມາດໃນການຂັດຂວາງ. ຂະບວນການວິນິດໄສໂດຍທົ່ວໄປແລ້ວແມ່ນກົງໄປກົງມາ—ອົງປະກອບບໍ່ວ່າຈະເຮັດວຽກ ຫຼື ພວກເຂົາບໍ່ໄດ້ເຮັດວຽກ, ໂດຍມີຮູບແບບຄວາມລົ້ມເຫຼວເປັນຕົ້ນຕໍແມ່ນກົນຈັກ ຫຼື ຄວາມຮ້ອນ.

ການແກ້ໄຂບັນຫາອຸປະກອນເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກ

ອຸປະກອນເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກຕ້ອງການວິທີການວິນິດໄສທີ່ແຕກຕ່າງກັນ. Oscilloscopes ເປີດເຜີຍບັນຫາຄວາມສົມບູນຂອງສັນຍານທີ່ເບິ່ງບໍ່ເຫັນຕໍ່ແມັດມາດຕະຖານ. Logic analyzers ຖອດລະຫັດບັນຫາການສື່ສານດິຈິຕອນ. ອົງປະກອບທີ່ລະອຽດອ່ອນຕໍ່ສະຖິດຮຽກຮ້ອງໃຫ້ມີ ການປ້ອງກັນ ESD ໃນລະຫວ່າງການຈັດການ ແລະ ການສ້ອມແປງ.

ຊອບແວ ແລະ ເຟີມແວເພີ່ມຄວາມສັບສົນໃຫ້ກັບການແກ້ໄຂບັນຫາອຸປະກອນເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກ. ການເຮັດວຽກຜິດປົກກະຕິ ໜ່ວຍເດີນທາງເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກ ອາດຈະມີການຕັ້ງຄ່າທີ່ເສຍຫາຍແທນທີ່ຈະເປັນຮາດແວທີ່ລົ້ມເຫຼວ. ຂໍ້ຜິດພາດໃນການຕັ້ງຄ່າສາມາດເຮັດໃຫ້ເກີດອາການທີ່ຄ້າຍຄືກັນກັບຄວາມລົ້ມເຫຼວຂອງອົງປະກອບ. ການແກ້ໄຂບັນຫາທີ່ປະສົບຜົນສຳເລັດຮຽກຮ້ອງໃຫ້ມີຄວາມເຂົ້າໃຈທັງຮາດແວ ແລະ ຊອບແວ.

ທ່າອ່ຽງໃນອະນາຄົດ: ການລວມຕົວຢ່າງຕໍ່ເນື່ອງ

ຂອບເຂດລະຫວ່າງອຸປະກອນໄຟຟ້າ ແລະ ເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກຍັງສືບຕໍ່ມົວເມື່ອເຕັກໂນໂລຊີກ້າວໜ້າ. ວົງຈອນຕັດໄຟ solid-state ໃຊ້ semiconductors ພະລັງງານເພື່ອຂັດຂວາງກະແສໄຟຟ້າໂດຍບໍ່ມີການຕິດຕໍ່ກົນຈັກ, ລວມຄວາມສາມາດພະລັງງານສູງຂອງອຸປະກອນໄຟຟ້າກັບຄວາມໄວ ແລະ ຄວາມສາມາດໃນການຄວບຄຸມຂອງເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກ. ອຸປະກອນປະສົມເຫຼົ່ານີ້ສັນຍາວ່າການປົກປ້ອງໄວຂຶ້ນ, ອາຍຸການໃຊ້ງານຍາວນານ, ແລະ ການເຊື່ອມໂຍງກັບລະບົບຄວບຄຸມດິຈິຕອນ.

ອິນເຕີເນັດຂອງສິ່ງຕ່າງໆ (IoT) ກຳລັງປ່ຽນອຸປະກອນໄຟຟ້າ “ໂງ່” ແບບດັ້ງເດີມໃຫ້ກາຍເປັນລະບົບທີ່ເຊື່ອມຕໍ່, ສະຫຼາດ. ອັດສະລິຍະ ເຄື່ອງຕັດວົງຈອນ ຕິດຕາມກວດກາການບໍລິໂພກພະລັງງານ, ກວດພົບຄວາມຜິດປົກກະຕິຂອງ arc, ແລະ ສື່ສານສະຖານະກັບລະບົບການຈັດການອາຄານ. ການເຊື່ອມຕໍ່ນີ້ເພີ່ມອົງປະກອບເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກໃສ່ອຸປະກອນທີ່ເຄີຍເປັນໄຟຟ້າຢ່າງດຽວ, ສ້າງຄວາມສາມາດໃໝ່ແຕ່ຍັງມີຄວາມສ່ຽງໃໝ່.

ເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກພະລັງງານ—ຂົງເຂດທີ່ເຊື່ອມຕໍ່ພະລັງງານໄຟຟ້າ ແລະ ການຄວບຄຸມເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກ—ສືບຕໍ່ກ້າວໜ້າຢ່າງໄວວາ. Wide-bandgap semiconductors ເຊັ່ນ: silicon carbide (SiC) ແລະ gallium nitride (GaN) ຊ່ວຍໃຫ້ອຸປະກອນເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກພະລັງງານທີ່ເຮັດວຽກຢູ່ແຮງດັນໄຟຟ້າ, ອຸນຫະພູມ, ແລະ ຄວາມຖີ່ສູງກວ່າອຸປະກອນ silicon ແບບດັ້ງເດີມ. ຄວາມກ້າວໜ້າເຫຼົ່ານີ້ຊ່ວຍໃຫ້ອຸປະກອນເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກສາມາດຈັດການລະດັບພະລັງງານທີ່ເຄີຍສະຫງວນໄວ້ສຳລັບອຸປະກອນໄຟຟ້າ.

ພາກສ່ວນ FAQ ສັ້ນ

ຖາມ: ຂ້ອຍສາມາດປ່ຽນອຸປະກອນໄຟຟ້າດ້ວຍອຸປະກອນເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກທີ່ທຽບເທົ່າໄດ້ບໍ?

ຕອບ: ໃນຫຼາຍໆກໍລະນີ, ແມ່ນແລ້ວ, ແຕ່ຕ້ອງກວດສອບຄວາມເຂົ້າກັນໄດ້. ການປ່ຽນແທນເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກມັກຈະມີຂໍ້ດີເຊັ່ນ: ຂະໜາດນ້ອຍລົງ, ການໃຊ້ພະລັງງານຕ່ຳກວ່າ, ແລະຄຸນສົມບັດທີ່ເພີ່ມຂຶ້ນ. ຢ່າງໃດກໍ່ຕາມ, ໃຫ້ແນ່ໃຈວ່າອຸປະກອນເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກສາມາດຮອງຮັບແຮງດັນ, ກະແສໄຟຟ້າ, ແລະສະພາບແວດລ້ອມຂອງແອັບພລິເຄຊັນຂອງທ່ານໄດ້. ຕົວຢ່າງ, ການປ່ຽນແທນກົນຈັກ ຣີເລຈັບເວລາ ດ້ວຍອຸປະກອນເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກຮຽກຮ້ອງໃຫ້ຢືນຢັນຄວາມເຂົ້າກັນໄດ້ຂອງແຮງດັນແລະຄວາມຕ້ອງການໃນການຕິດຕັ້ງ.

ຖາມ: ອຸປະກອນເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກມີຄວາມໜ້າເຊື່ອຖືຫຼາຍກວ່າອຸປະກອນໄຟຟ້າບໍ?

ຕອບ: ຄວາມໜ້າເຊື່ອຖືແມ່ນຂຶ້ນກັບແອັບພລິເຄຊັນ. ອຸປະກອນໄຟຟ້າທີ່ມີສ່ວນປະກອບໜ້ອຍກວ່າ ແລະໂຄງສ້າງກົນຈັກມັກຈະພິສູດໄດ້ວ່າມີຄວາມທົນທານຫຼາຍກວ່າໃນສະພາບແວດລ້ອມທີ່ຮຸນແຮງ. ອຸປະກອນເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກ, ທີ່ບໍ່ມີຊິ້ນສ່ວນເຄື່ອນທີ່, ສາມາດບັນລຸອາຍຸການໃຊ້ງານທີ່ຍາວນານກວ່າໃນສະພາບທີ່ຄວບຄຸມໄດ້ ແຕ່ອາດຈະມີຄວາມສ່ຽງຕໍ່ແຮງດັນໄຟຟ້າຊົ່ວຄາວ, ອຸນຫະພູມທີ່ຮຸນແຮງ, ແລະການລົບກວນແມ່ເຫຼັກໄຟຟ້າ. ທີ່ເໝາະສົມ ການປ້ອງກັນກະແສໄຟຟ້າ ແລະການຄວບຄຸມສະພາບແວດລ້ອມແມ່ນມີຄວາມຈຳເປັນສຳລັບຄວາມໜ້າເຊື່ອຖືຂອງອຸປະກອນເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກ.

ຖາມ: ເປັນຫຍັງອຸປະກອນບາງອັນຈຶ່ງມີທັງສ່ວນປະກອບໄຟຟ້າ ແລະເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກ?

ຕອບ: ອຸປະກອນທີ່ທັນສະໄໝນັບມື້ນັບລວມເອົາທັງສອງເທັກໂນໂລຢີເພື່ອໃຊ້ປະໂຫຍດຈາກຈຸດແຂງຂອງແຕ່ລະອັນ. ກ ຕົວເລີ່ມມໍເຕີ (motor starter) ອາດຈະໃຊ້ contactors ໄຟຟ້າສໍາລັບການປ່ຽນພະລັງງານ (ຄວາມສາມາດໃນການກະແສໄຟຟ້າສູງ, ຕໍາແຫນ່ງຕິດຕໍ່ທີ່ເຫັນໄດ້) ໃນຂະນະທີ່ໃຊ້ການຄວບຄຸມເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກສໍາລັບການກໍານົດເວລາທີ່ຊັດເຈນ, ການປົກປ້ອງມໍເຕີ, ແລະການສື່ສານ. ວິທີການປະສົມນີ້ໃຫ້ຄວາມສາມາດທີ່ເປັນໄປບໍ່ໄດ້ກັບເຕັກໂນໂລຢີໃດໆຢ່າງດຽວ.

ຖາມ: ອຸປະກອນເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກຕ້ອງການຂໍ້ຄວນພິຈາລະນາໃນການຕິດຕັ້ງພິເສດບໍ?

ຕອບ: ແມ່ນແລ້ວ, ອຸປະກອນເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກມີຄວາມຕ້ອງການສະເພາະ. ພວກເຂົາຕ້ອງການການສະຫນອງພະລັງງານທີ່ສະອາດແລະຄວບຄຸມ - ມັກຈະຕ້ອງການ isolation transformers ຫຼືຕົວກອງເພື່ອປ້ອງກັນການລົບກວນ. ທີ່ເໝາະສົມ grounding ແມ່ນສິ່ງທີ່ສໍາຄັນເພື່ອປ້ອງກັນສຽງແລະຮັບປະກັນຄວາມປອດໄພ. ການຄວບຄຸມອຸນຫະພູມມີຄວາມສໍາຄັນຫຼາຍສໍາລັບເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກກ່ວາອຸປະກອນໄຟຟ້າ, ເນື່ອງຈາກວ່າປະສິດທິພາບຂອງ semiconductor ເສື່ອມໂຊມໃນອຸນຫະພູມສູງ. Cable routing ຄວນແຍກສາຍໄຟແລະສາຍສັນຍານເພື່ອຫຼຸດຜ່ອນການລົບກວນແມ່ເຫຼັກໄຟຟ້າ.

ຖາມ: ຂໍ້ຄວນລະວັງດ້ານຄວາມປອດໄພອັນໃດທີ່ເປັນເອກະລັກຂອງອຸປະກອນເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກ?

ຕອບ: ໃນຂະນະທີ່ອຸປະກອນໄຟຟ້າກໍ່ໃຫ້ເກີດອັນຕະລາຍຈາກການຊ໊ອກຈາກແຮງດັນໄຟຟ້າສູງ, ອຸປະກອນເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກຕ້ອງການການປົກປ້ອງຈາກການໄຫຼອອກຂອງໄຟຟ້າສະຖິດ (ESD). ໃຊ້ grounding ທີ່ເຫມາະສົມສະເຫມີໃນເວລາທີ່ຈັດການອົງປະກອບເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກ. ຈົ່ງລະວັງວ່າອຸປະກອນເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກອາດຈະຍັງຄົງມີພະລັງງານເຖິງແມ່ນວ່າພະລັງງານຈະປິດ - capacitors ສາມາດເກັບຮັກສາຄ່າບໍລິການທີ່ເປັນອັນຕະລາຍ. ນອກຈາກນັ້ນ, ອຸປະກອນເອເລັກໂຕຣນິກມັກຈະມີ firmware ແລະຊອບແວທີ່ສາມາດເສຍຫາຍໄດ້, ຮຽກຮ້ອງໃຫ້ມີຂັ້ນຕອນການສໍາຮອງຂໍ້ມູນກ່ອນການບໍາລຸງຮັກສາຫຼືການປັບປຸງ.