공급업체의 이메일이 도착했을 때 패널 사양의 중간 단계에 있습니다. “NEC에 따른 GFCI 보호를 요청하는 것인지, IEC 61009에 따른 RCD 보호를 요청하는 것인지 명확히 해 주시겠습니까?”

화면을 멍하니 쳐다봅니다. 그들은 같은 것이 아닌가요?

그렇습니다. 일종의. 장치는 동일한 작업을 수행하지만 용어, 표준 번호 매기기, 정격 명명법 및 테스트 매개변수까지 다릅니다. 미국에서 교육받은 당신의 두뇌는 “GFCI”라고 말합니다. 국제 공급업체의 데이터시트에는 “RCBO”라고 나와 있습니다. 멕시코의 패널 제작자는 텍사스 고객과 유럽 고객에게 서비스를 제공하기 때문에 두 용어가 모두 필요합니다. 하나의 장치. 두 가지 언어. 사양서에서 이들을 혼동하면 잘못된 장비, 혼란스러운 견적 또는 모든 사람이 실제로 의미하는 바를 명확히 하는 데 3주 지연이 발생할 수 있습니다.

이 가이드는 해독기입니다. 번역 오류 없이 시장 전반에서 장비를 사양, 소싱 및 설치할 수 있도록 NEC(National Electrical Code, 미국에서 지배적)와 IEC(International Electrotechnical Commission, 거의 모든 곳에서 사용) 간의 주요 대응 관계를 매핑합니다.

이 용어 대응이 중요한 이유

이는 학문적인 말장난이 아닙니다. 국제 제조업체에서 장비를 소싱하거나, 다국적 시설용 패널을 설계하거나, 미국 및 비 미국 설치에 걸쳐 있는 프로젝트에 대해 컨설팅하는 등 국경을 넘어 작업할 때 용어 불일치로 인해 실제 비용이 발생합니다.

사양 오류: 유럽 공급업체에 보낸 사양서에 “GFCI”를 작성합니다. 그들은 견적을 냅니다. RCCB (과전류 보호 기능이 없는 잔류 전류 회로 차단기)는 카탈로그에서 가장 가까운 일치 항목이기 때문입니다. RCBO(통합 과전류 보호 기능 포함)가 필요했습니다. 패널이 도착하고 보호 체계가 불완전합니다. 재주문, 재배송, 지연.

소싱 혼란: 귀하의 조달 팀은 아시아 공급업체로부터 “IP65 인클로저”에 대한 훌륭한 가격을 찾습니다. 귀하의 NEC 기반 프로젝트 사양은 NEMA 4X(내식성, 호스다운 보호)를 요구했습니다. 그들은 동등한가요? 꼭 그렇지는 않습니다. NEMA 4X에는 IP65에서 다루지 않는 추가적인 내식성 테스트 및 호스다운 요구 사항이 포함되어 있습니다. 설치하면 6개월 후 해안 염수 분무로 인해 인클로저 개스킷이 부식됩니다. 하나의 등급 시스템이 다른 등급 시스템으로 직접 변환되지 않습니다.

표준 준수 격차: 계약자는 IEC 60947-2를 설치합니다. MCCB 미국 시설에서 “회로 차단기”가 모든 곳에서 동일한 의미를 갖는다고 가정합니다. AHJ(관할 당국)는 NEC 요구 사항에 따라 UL 489에 등재된 차단기를 요청합니다. IEC 60947-2 차단기는 UL에 등재되지 않았습니다. 검사가 실패합니다. 재작업, 교체, 누가 비용을 지불할지에 대한 논쟁.

디코더 링 문제- 한 시스템에 능통하지만 다른 시스템에는 문맹인 엔지니어로 인해 잘못된 사양, 조달 지연 및 간단한 용어 번역으로 피할 수 있었던 현장 오류가 발생합니다. 이것이 바로 이 가이드가 수정하는 것입니다.

5가지 주요 용어 범주

NEC-IEC 분할은 5가지 주요 영역에서 나타납니다. 각 영역에는 고유한 대응 규칙과 일반적인 함정이 있습니다.

- 회로 보호 장치 (GFCI 대 RCD, AFCI 대 AFDD, 차단기 제품군)

- 전기 등급 (전압, 전류, 차단 용량 명명법)

- 인클로저 보호 등급 (NEMA 유형 대 IP 코드)

- 접지 대 접지 언어 (EGC 대 PE 도체)

- 표준 번호 매기기 시스템 (NEC 조항 대 IEC 표준 시리즈)

대응 테이블과 실용적인 디코딩 규칙을 사용하여 각 문제를 해결할 것입니다.

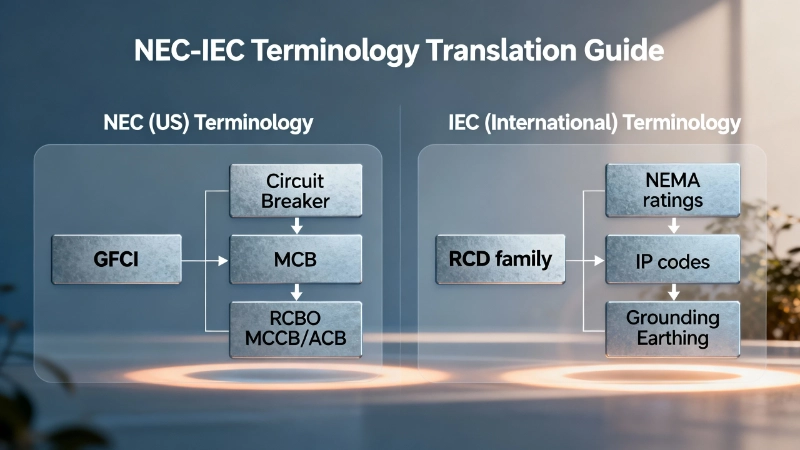

범주 1: 회로 보호 장치

여기서 가장 많은 혼란이 발생합니다. 미국에서는 “GFCI” 및 “회로 차단기”와 같은 포괄적인 용어를 사용하며, 이는 각각 고유한 표준과 범위를 가진 여러 개의 개별 IEC 장치 제품군에 매핑됩니다.

| NEC/미국 용어 | IEC 해당 용어 | IEC 표준 | 주요 차이점 및 참고 사항 |

|---|---|---|---|

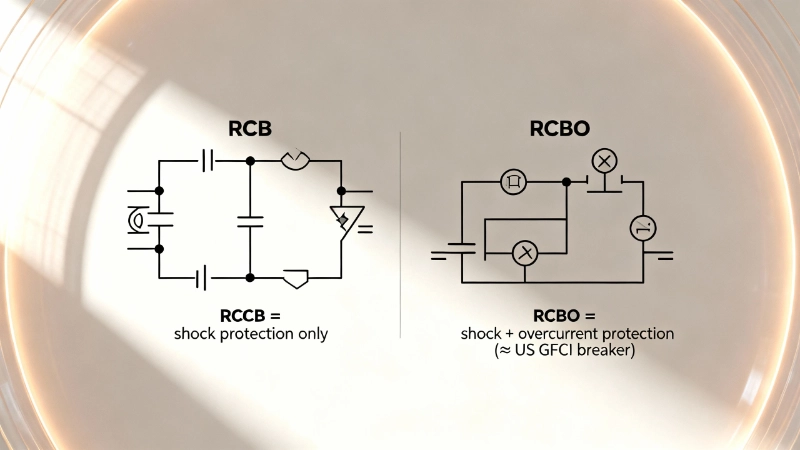

| GFCI (접지 오류 회로 차단기) | RCD 가족 | IEC 61008(RCCB), IEC 61009(RCBO) | RCCB = 잔류 전류 회로 차단기 없이 통합 과전류 보호(충격 보호만 해당). RCBO = 잔류 전류 차단기 와 함께 통합 과전류 보호. 미국 “GFCI 차단기” ≈ IEC RCBO. |

| AFCI (아크 오류 회로 차단기) | AFDD (아크 오류 감지 장치) | IEC 62606 | 배선에서 위험한 아크 오류를 모두 감지합니다. IEC는 “감지 장치” 언어를 사용합니다. 기능은 동일합니다. 침실/거실(미국 NEC) 및 유사한 공간(가정용 설치용 IEC)에 필요합니다. |

| 회로 차단기 (일반) | MCB 나 MCCB/ACB | IEC 60898-1(MCB), IEC 60947-2(산업용) | MCB (소형 회로 차단기) 가정용/최종 회로용 IEC 60898-1에 따름, 최대 125A, 일반인이 설치합니다. MCCB/ACB 산업/배전용 IEC 60947-2에 따름, 더 높은 정격, 숙련된 사람만 설치합니다. |

| 몰드 케이스 회로 차단기(MCCB) | MCCB | IEC 60947-2 | 동일한 용어이지만 IEC 60947-2 범위가 더 넓습니다(ACB 포함). UL 489에 따른 미국 MCCB. NEC 설치의 경우 항상 UL 목록을 확인하십시오. IEC 준수만으로는 충분하지 않습니다. |

| 메인 차단기 | 설치 CB의 원점 | IEC 60364(설치), IEC 60947-2 | IEC는 이를 “설치 원점”의 차단기라고 부릅니다. 기능은 동일합니다. 전체 패널 또는 하위 패널에 대한 주 차단 및 과전류 보호입니다. |

| 분기 회로 차단기 | 최종 회로 차단기 | IEC 60898-1, IEC 60364 | 미국 “분기 회로” = IEC “최종 회로”. 개별 부하 또는 콘센트 회로를 보호하는 차단기. 용어 교환, 동일한 기능. |

프로 끝#1: 보호 장치를 국제적으로 소싱할 때는 기능(“과전류가 있는 잔류 전류 보호”)과 IEC 용어(“IEC 61009에 따른 RCBO”)를 모두 지정하십시오. “GFCI”에만 의존하지 마십시오. 공급업체에서 명확한 설명을 요청하고 이메일 핑퐁으로 일주일을 낭비하게 됩니다.

범주 2: 전기 정격 명명법

정격 라벨은 비교하기 전까지는 비슷해 보입니다. NEC 교육을 받은 사람들은 특정 단위와 형식을 기대합니다. IEC 데이터시트는 다른 규칙을 사용합니다. 뉘앙스를 놓치면 과도하게 사양(돈 낭비)하거나 사양 부족(현장 오류)이 발생합니다.

| 정격 매개변수 | NEC/미국 규칙 | IEC 협약 | 주요 차이점 및 번역 참고 사항 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 단 용량 | AIC kA 단위의 (차단 용량) | Icn kA 단위의 (정격 단락 차단 용량) 또는 Icu (최대 차단 용량) | 미국 데이터시트: “10,000 AIC” 또는 “10 kA AIC”. IEC 데이터시트: Icn 또는 Icu (kA 단위). MCB(IEC 60898-1)의 경우 용량은 다음과 같이 표시됩니다. 사각형 안의 암페어 (예: 6000은 6,000A = 6 kA를 의미). 산업용 CB(IEC 60947-2)의 경우 kA 단위로 직접 표시됩니다. |

| 전압 평가 | 120V, 240V, 480V (일반적인 미국 전압) | 230V, 400V (일반적인 EU 전압); IEC 60947-2에 따라 최대 1000V AC 정격 | 미국은 120/240V 단상 주거용, 480V 산업용을 사용합니다. IEC는 230/400V 3상을 사용합니다. 장치 전압 정격은 시스템 전압을 초과해야 합니다. 공칭 및 최대 전압(Ue vs Uimp)을 모두 확인하십시오. |

| 현재 평가 | 암페어(A), 차단기 핸들 또는 라벨에 표시 | 암페어(A), 차단기에 표시; RCBO/RCCB는 최신 표준에 따라 ≤125A 정격 | 동일한 단위이지만 다음 사항에 유의하십시오. 열동 트립 대 순시 트립 조정 가능한 차단기의 설정. 미국 차단기: 연속 정격. IEC MCCB: In (정격 전류) 및 해당되는 경우 조정 가능한 열동 트립. |

| 정격 주파수 | 60 Hz (미국 표준) | 50 Hz 또는 50/60 Hz (IEC 장치는 종종 이중 정격) | 대부분의 최신 IEC 장치는 50/60 Hz로 정격되어 있으므로 상호 호환성이 일반적입니다. 구형 장치는 50 Hz 전용일 수 있습니다. 미국 60 Hz 시스템에 지정하기 전에 확인하십시오. |

| 잔류 전류 (RCD) | 트립 전류 mA 단위 (예: 5 mA, 30 mA) | IΔn mA 단위의 (정격 잔류 작동 전류) | 동일한 매개변수, 다른 기호. 30 mA는 두 시스템 모두에서 감전 보호를 위한 일반적인 임계값입니다. IEC는 IΔn을 사용합니다. 미국 데이터시트는 “트립 전류” 또는 “감도”라고 합니다.” |

Pro-Tip#2: 차단 용량을 비교할 때 IEC MCB 표시 함정을 주의하십시오. 사각형 안의 “6000”은 6 암페어가 아닌 6,000 암페어(6 kA)를 의미합니다. 산업용 차단기(IEC 60947-2)는 kA 단위로 직접 표시됩니다. 이 둘을 혼동하면 과소 사양 및 치명적인 단락 고장으로 이어집니다.

카테고리 3: 인클로저 보호 등급 (NEMA vs IP)

이것은 모든 사람이 원하고 아무도 맹목적으로 신뢰해서는 안 되는 대응 관계입니다. NEMA 250 인클로저 유형과 IEC 60529 IP 코드는 모두 환경 보호를 설명하지만 다른 것을 테스트하고 다른 방법을 사용하며 다른 위험을 다룹니다. 공식 NEMA 지침(BI 50014–2024)은 다음과 같이 명확하게 설명합니다. 직접적으로 동일하지 않습니다.

| NEMA 유형 | 가장 가까운 IP 코드 (대략) | NEMA 유형이 다루는 내용 | IP 코드가 다루는 내용 | 중요한 차이점 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEMA 1 | IP10 (매우 대략적) | 실내, 범용, 우발적인 접촉으로부터 보호 | 제한된 보호 (IP1X = ≥50mm 물체) | NEMA 1에는 IP10에는 없는 구조 테스트(강성, 도어 래치 강도)가 포함됩니다. 진정한 일치가 아닙니다. |

| NEMA 3 | IP54 | 실외, 비/진눈깨비/바람에 날리는 먼지, 호스 세척 또는 침수되지 않음 | 방진, 튀는 물 | NEMA 3은 얼음/진눈깨비 요구 사항 및 부식 테스트를 추가합니다. IP54는 먼지와 튀는 물만 테스트합니다. 가깝지만 NEMA 3이 더 광범위합니다. |

| 네마 3R | IP24 에게 IP34 | 실외, 비/진눈깨비, 약간의 먼지와 물 유입 허용 | 다양함; IP24는 최소(튀는), IP34는 약간 더 나음 | NEMA 3R은 더 저렴한 실외 옵션(방진 요구 사항 없음)입니다. IP 코드만으로는 실외 UV/진눈깨비 성능을 보장하지 않습니다. |

| NEMA 4 | IP66 | 호스 세척/튀는 물, 방진, 실내 또는 실외 | 방진, 강력한 물 분사 | 먼지 및 물 유입에 대한 근접 일치. NEMA 4는 내식성 및 구조 테스트(힌지/래치 내구성)를 추가합니다. IP66은 유입만 다룹니다. |

| 네마 4X | IP66 (부분) | NEMA 4와 동일, 내식성 추가 (스테인리스 스틸, 코팅) | 방진, 강력한 물 분사 | NEMA 4X의 내식성은 IP66에서 다루지 않는 별도의 테스트입니다. IP66 등급의 연강 인클로저는 해안 환경에서 녹슬습니다. NEMA 4X는 명시적으로 부식 방지를 요구합니다. |

| NEMA 12 | IP54 나 IP55 | 실내, 먼지/흙/보풀, 떨어지는/튀는 비부식성 액체 | 방진, 튀는 또는 저압 분사 | 근접 일치, 그러나 NEMA 12에는 내유성 테스트(개스킷은 산업용 오일에 저항해야 함)가 포함됩니다. IP 코드는 내화학성을 테스트하지 않습니다. |

| NEMA 13 | IP54 (대략) | 실내, 먼지/보풀, 분무되는 물, 오일/냉각수 누출 | 방진, 튀는 물 | NEMA 13은 오일/냉각수 저항 테스트(분무/누출)를 추가합니다. IP54는 물만 테스트하고 오일은 테스트하지 않습니다. 공작 기계 응용 분야에는 해당하지 않습니다. |

왜 그냥 바꿀 수 없는가

NEMA 2024 요약본은 이를 명확히 합니다. NEMA 유형에는 다음이 포함됩니다. 부식 테스트, 구조적 무결성 테스트(힌지 주기, 래치 강도) 및 특정 환경 위험(얼음, 오일, 냉각수) IP 코드가 다루지 않는 사항. IP 코드는 좁게 집중합니다. 고체 및 액체의 침투—인클로저가 부식될지, 도어 래치가 10,000회 사이클을 견딜지, 개스킷이 유압 오일에 저항할지에 대해서는 아무것도 말하지 않습니다.

사양에 NEMA 4X라고 되어 있고 공급업체가 IP66을 견적하는 경우 “인클로저 재료가 NEMA 250 테스트에 따라 내식성이 있습니까?”라고 물어보십시오. “IP66이 그것을 다룹니다.”라고 말하면 틀린 것입니다. 6개월 안에 부식되는 연강 IP66 상자를 설치하려고 합니다.

프로 끝#3: 추가 테스트 요구 사항을 확인하지 않고는 IP 코드를 NEMA 유형으로 대체하지 마십시오(또는 그 반대). 부식되기 쉬운 환경(해안, 화학 공장, 살균제가 있는 식품 가공)의 경우 NEMA 4X는 IP66에 포함되지 않은 부식 테스트를 명시적으로 요구합니다. 두 시스템 모두 준수가 필요한 경우 둘 다 지정하거나 해당 관할 구역에 맞는 시스템을 선택하고 모든 테스트 매개변수를 확인하십시오.

카테고리 4: 접지 대 접지 용어

미국은 “접지”라고 합니다. 나머지 세계는 “접지”라고 합니다. 동일한 개념, 다른 어휘. 그러나 도체 지정 및 색상 코드도 다르며, 여기서 배선 오류가 발생합니다.

| NEC/미국 용어 | IEC 용어 | 색상 코드(US/NEC) | 색상 코드(IEC) | 참고 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 접지 | : 배터리에 직접 연결된 어레이의 경우, 절연 모니터링 또는 잔류 전류 감지를 포함한 추가 보호 조치 | — | — | 개념적 용어. NEC는 모든 것에 “접지”를 사용합니다. IEC는 접지에 대한 연결에는 “접지”를 사용하고 PE 시스템에 대한 연결에는 “본딩”을 사용합니다. |

| 장비 접지 도체(EGC) | 보호 도체(PE) | 녹색 또는 녹색/노란색 | 녹색/노란색 | 두 용어 모두 충격 보호를 위해 장비 프레임/인클로저를 접지에 연결하는 도체를 설명합니다. IEC는 거의 보편적으로 “PE”를 사용합니다. |

| 접지 전극 도체(GEC) | 접지 도체 | 녹색 또는 노출 | 녹색/노란색 또는 노출 | 전기 시스템의 중성/접지 지점을 접지 전극(로드, 플레이트 등)에 연결하는 도체입니다. |

| 접지된 도체 | 중성 도체(N) | 흰색 또는 회색 | 파란색(단상), 다양함(3상) | 미국 분할 상 시스템에서 접지된 도체는 중성선입니다. IEC는 단상에서는 중성선에 파란색을 사용하고 3상에서는 특정 코드를 사용합니다. |

| 접착 | 보호 본딩 / 등전위 본딩 | — | — | 전압 차이를 방지하기 위해 전도성 부품을 함께 연결합니다. 미국과 IEC 모두 “본딩”을 사용하지만 IEC는 용어에서 더 명확합니다. |

기능적 차이는 최소화됩니다. 여전히 안전을 위해 금속 인클로저를 접지에 연결합니다. 그러나 다국적 프로젝트에서는 문서가 명확해야 합니다. “EGC 연결”이라고 쓰면 IEC 교육을 받은 전기 기술자가 즉시 인식하지 못할 수 있습니다. 명확성을 위해 “보호 도체(PE) 연결” 또는 “EGC/PE”라고 쓰십시오.

색상 코드 함정: 미국 중성선은 흰색입니다. IEC 단상 중성선은 파란색입니다. 미국 패널에서 흰색 도체를 보는 IEC 교육을 받은 전기 기술자는 그것이 상 도체라고 가정할 수 있습니다(흰색은 IEC에서 상에 사용되지 않지만 중성선도 아님). 특히 혼합 표준 설치 또는 국제 프로젝트에서는 모든 것에 레이블을 붙이십시오.

카테고리 5: 표준 번호 매기기 시스템

NEC는 조항 및 섹션을 사용합니다(예: 모터의 경우 NEC 조항 430, 접지의 경우 조항 250). IEC는 부품 및 하위 부품을 나타내는 대시가 있는 숫자 표준 시리즈를 사용합니다. 일대일로 매핑되지는 않지만 여기에 방향이 있습니다.

| NEC 조항/섹션 | 대략적인 IEC 표준 해당 항목 | 범위 |

|---|---|---|

| NEC 조항 100 (정의) | IEC Electropedia (IEV) | 정의. IEC의 국제 전기 기술 어휘는 글로벌 참조입니다. |

| NEC 조항 250 (접지) | IEC 60364-4-41, IEC 60364-5-54 | 설치에 대한 접지 및 보호 도체 요구 사항. |

| NEC 조항 430 (모터) | IEC 60034(회전 기계), IEC 60947-4-1(접촉기/스타터) | 모터 요구 사항 및 모터 제어 장비. |

| NEC 조항 440 (HVAC) | IEC 60335-2-40(열 펌프, 에어컨) | HVAC 관련 안전 및 설치 규칙. |

| UL 489 (회로 차단기) | IEC 60947-2(산업용 CB), IEC 60898-1(가정용 MCB) | 미국 몰드 케이스 및 저전압 회로 차단기 대 IEC 제품군. |

| UL 943 (GFCI) | IEC 61008(RCCB), IEC 61009(RCBO) | 접지 오류 / 잔류 전류 보호 장치. |

| NEMA 250 (인클로저) | IEC 60529 (IP 코드) | 인클로저 침투 보호. 위에서 설명한 것처럼 동일하지 않습니다. |

IEC 번호 매기기 논리: 60947 는 저전압 개폐 장치 제품군이고, 60947-2 는 해당 제품군 내의 회로 차단기입니다., 60947-4-1 은 접촉기 및 모터 기동기입니다. 대시는 주제(60947 = 개폐 장치), 부품(2 = 차단기) 및 하위 부품(4-1 = 접촉기)을 나눕니다. NEC는 계층적 대시 시스템 없이 순차적 조항 번호를 사용합니다.

사양을 작성할 때 프로젝트가 여러 관할 구역에 걸쳐 있는 경우 둘 다 인용하십시오. “회로 차단기는 해당되는 경우 UL 489(미국 설치용) 또는 IEC 60947-2(국제 설치용)를 준수해야 합니다.”

세 가지 일반적인 혼동 함정(및 이를 피하는 방법)

숙련된 엔지니어조차도 NEC와 IEC 세계 사이를 이동할 때 이러한 함정에 빠집니다. 피하는 방법은 다음과 같습니다.

함정 1: “회로 차단기”가 같은 의미라고 가정

문제점: 미국에서는 “회로 차단기”가 포괄적인 용어입니다. IEC에서는 다음을 구별해야 합니다. MCB(IEC 60898-1) 가정/최종 회로용 및 MCCB/ACB(IEC 60947-2) 산업/배전 애플리케이션용. 모양은 비슷하지만 다른 표준의 적용을 받고, 다른 전압 임펄스 정격(Uimp)을 가지며, 다른 사용자를 대상으로 합니다.

IEC 60898-1 MCB는 가정 및 경상업용 건물에 최종 회로를 설치하는 일반인을 위해 설계되었습니다. 최대 125A, 일반적으로 더 낮은 차단 용량(최대 25 kA Icn) 및 더 간단한 조정 요구 사항이 있습니다. IEC 60947-2 산업용 차단기는 숙련된 전기 기술자용이며, 더 높은 전류 및 전압(2024년 판에 따라 최대 1000V AC / 1500V DC)을 다루며, 절연 적합성 및 EMC에 대한 더 엄격한 테스트를 포함합니다.

실제 고장 사례: 한 계약자는 “더 저렴하고 전류 정격이 적합하기 때문에” 제조 시설의 주 배전반에 IEC 60898-1 MCB를 지정했습니다. 6개월 후 생산 현장에서의 3상 고장으로 35 kA 단락 전류가 발생했습니다. MCB(정격 Icn = 10 kA)는 치명적으로 고장났습니다. 접점이 용접되고, 인클로저가 파손되었습니다. 근본 원인: 잘못된 차단기 제품군. 사양은 Icu ≥50 kA인 IEC 60947-2 MCCB를 요구했어야 했습니다.

피하는 방법: 다음 질문을 스스로에게 던지십시오. 이것이 최종 회로(조명, 콘센트, 소형 부하)입니까, 아니면 배전/피더 회로(주 패널, 하위 패널, 대형 모터 피더)입니까? 최종 회로 → IEC 60898-1 MCB. 배전/산업용 → IEC 60947-2 MCCB 또는 ACB. 확실하지 않은 경우 사용 가능한 고장 전류를 확인하고 차단기의 정격 차단 용량(Icn 또는 Icu)과 비교하십시오. 고장 전류가 차단기의 용량을 초과하면 잘못된 장치를 지정한 것입니다.

함정 2: IEC 차단 용량 표시 오독

문제점: IEC 60898-1 MCB는 단락 회로 용량을 다음과 같이 표시합니다. 사각형 안의 암페어—예를 들어 “6000”은 6,000암페어 또는 6 kA를 의미합니다. IEC 60947-2 산업용 차단기는 용량을 다음과 같이 직접 표시합니다. kA. 주의를 기울이지 않으면 MCB에서 “6000”을 보고 “6 kA”라고 생각하는데, 이는 맞습니다. 그러나 산업용 차단기에서 “10”을 보고 “10암페어”라고 생각하면 치명적으로 잘못된 것입니다. 10 kA(10,000암페어)입니다.

피하는 방법: 항상 차단기가 인증된 표준을 확인하십시오(레이블에서 “IEC 60898-1” 또는 “IEC 60947-2”를 찾으십시오). 60898-1이면 사각형 안의 숫자는 암페어입니다(kA의 경우 1000으로 나눕니다). 60947-2이면 표시는 이미 kA 단위입니다. 확실하지 않은 경우 데이터시트의 Icn 또는 Icu 행을 참조하십시오. 단위가 명확해집니다.

함정 3: NEMA 4X와 IP66을 동일하게 취급

위에서 다루었지만 #1 인클로저 사양 오류이므로 반복할 가치가 있습니다.

문제점: NEMA 4X에는 내식성 테스트(염수 분무, 스테인리스 스틸 또는 내식성 코팅과 같은 특정 재료)가 포함됩니다. IP66은 먼지 및 물 침투만 테스트합니다. 연강 인클로저는 IP66 등급을 받을 수 있지만 IP66은 부식을 테스트하지 않기 때문에 해안 또는 화학 환경에서 여전히 녹슬 수 있습니다.

실제 고장 사례: 한 식품 가공 시설은 공격적인 살균제(염소 기반)가 있는 세척 구역의 제어 패널에 NEMA 4X 인클로저를 지정했습니다. 조달 부서는 해외 공급업체에서 “동등한” IP66 인클로저(도장된 연강)를 조달했습니다. 8개월 이내에 살균제 스프레이가 페인트를 부식시키고 인클로저를 녹슬게 하여 도어 개스킷 씰을 손상시켰습니다. 물 침투로 인해 PLC가 손상되어 가동 중지 시간 및 교체 비용이 $15,000 발생했습니다. NEMA 4X는 살균제를 견딜 수 있는 스테인리스 스틸 또는 내식성 코팅을 요구했을 것입니다.

피하는 방법: 사양에 NEMA 4X가 필요한 경우 IP 등급에 관계없이 인클로저 재료 및 코팅이 NEMA 250의 내식성 요구 사항을 충족하는지 확인하십시오. IP66을 NEMA 4X로 대체하는 경우 공급업체로부터 인클로저가 ASTM B117 또는 동등한 염수 분무 테스트에 따라 부식 테스트를 거쳤다는 서면 확인을 받으십시오. 더 나은 방법은 프로젝트에 NEC 및 IEC 규정 준수가 모두 필요한 경우 두 등급을 모두 지정하는 것입니다. ’인클로저는 NEMA 250에 따른 NEMA 4X여야 합니다. 그리고 IEC 60529에 따른 IP66, 스테인리스 스틸 구조 또는 ASTM B117에 따른 염수 분무 테스트로 검증된 내식성 코팅이 있어야 합니다.”

프로 끝#4: 위의 세 가지 함정은 시스템 간 사양 오류의 약 70%를 차지합니다. 암기하거나 이 섹션을 인쇄하여 모니터에 붙여 놓으십시오. NEC-IEC 경계를 넘을 수 있는 사양에 “회로 차단기”, “차단 용량” 또는 “인클로저 등급”을 작성할 때마다 어떤 시스템에 있는지, 용어가 실제로 동일한지 다시 확인하십시오.

시스템 간 사양 체크리스트

이 가이드의 모든 대응 관계를 암기할 필요는 없습니다. 괜찮습니다. 필요한 것은 구매 주문서가 되기 전에 번역 오류를 포착하는 체크리스트입니다.

NEC 및 IEC 시스템에 걸쳐 있을 수 있는 사양, RFQ 또는 장비 목록을 확정하기 전에 다음을 실행하십시오.

- ☐ 보호 장치: 다음을 지정했습니까? 기능 (“과전류가 있는 잔류 전류 보호”) 용어(“GFCI” 또는 “RCBO”) 외에? “GFCI”라고 썼다면 RCCB(과전류 없음) 또는 RCBO(과전류 있음)가 필요한지 명확히 했습니까?

- ☐ 회로 차단기: 최종 회로 차단기(IEC 60898-1 MCB)와 산업/배전 차단기(IEC 60947-2 MCCB/ACB)를 구별했습니까? 올바른 단위(사각형의 kA 대 암페어)로 차단 용량을 확인했습니까?

- ☐ 인클로저: 다음을 사용하여 환경 보호를 지정했습니까? 둘 다 프로젝트가 여러 관할 구역에 걸쳐 있는 경우 NEMA 유형 및 IP 코드? 하나를 다른 것으로 대체한 경우 한 시스템이 다루고 다른 시스템이 다루지 않는 부식 저항, 구조 테스트 및 환경 위험(얼음, 오일, 냉각수)을 확인했습니까?

- ☐ 접지/접속: 다국적 팀을 위한 문서에서 두 용어(“EGC/PE” 또는 “접지/접속”)를 모두 사용했습니까? 시스템 간 배선 오류를 방지하기 위해 도체 색상 코드를 명시적으로 지정했습니까?

- ☐ 표준 인용: 해당되는 경우 NEC 조항과 IEC 표준을 모두 인용했습니까(“관할 구역에 따라 NEC 조항 430 및 IEC 60947-4-1에 따름”)? IEC 준수 장치가 미국 설치에 필요한 UL/CSA 목록을 가지고 있는지 확인했습니까?

- ☐ 전압 및 주파수: 50Hz 정격의 IEC 장치가 60Hz 시스템에서 작동하는지 확인했습니까(대부분의 최신 장치는 이중 정격 50/60Hz이지만 구형 장치는 그렇지 않을 수 있음)? 전압 호환성(120V 대 230V, 240V 대 400V)을 확인했습니까?

RFQ에서 “보내기”를 누르거나 구매 주문서에서 “승인”을 누르기 전에 해당 체크리스트를 실행하십시오. NEMA 4X 대 IP66 오류 하나를 잡으면 $15,000과 3주 지연을 방지할 수 있습니다. 차단 용량 오독을 잡으면 누군가를 다치게 할 수 있는 치명적인 고장을 예방할 수 있습니다.

参考标准与来源

- IEC 60947-2:2024(저전압 개폐 장치 및 제어 장치 – 파트 2: 회로 차단기, 에디션 6.0, 2024-09-18 발행)

- IEC 61009-1:2024(통합 과전류 보호 기능이 있는 잔류 전류 회로 차단기 – RCBO, 에디션 4.0, 2024-11-21 발행)

- IEC 61008-2-1:2024(통합 과전류 보호 기능이 없는 잔류 전류 회로 차단기 – RCCB, 에디션 2.0, 2024-11-21 발행)

- IEC 62606(아크 고장 감지 장치에 대한 일반 요구 사항, 2022년까지 통합 버전)

- IEC 60898-1(가정 및 유사 설치의 과전류 보호용 회로 차단기 – MCB)

- IEC 60529(인클로저에서 제공하는 보호 등급 – IP 코드)

- NEMA 250-2020(电气设备外壳,最大电压1000伏)

- NEMA BI 50014–2024(NEMA 250 및 IEC 60529의 간략한 비교)

- NEC 2023(NFPA 70, 국가 전기 코드)

- UL 489(몰드 케이스 회로 차단기, 몰드 케이스 스위치 및 회로 차단기 인클로저)

- UL 943(지락 회로 차단기)

- IEC Electropedia(IEV 826-13-22, 보호 도체 정의)

时效声明

모든 표준 버전, 기술 사양 및 서신 지침은 2025년 11월 현재 정확합니다.