អ្នកកំពុងសម្លឹងមើលសន្លឹកទិន្នន័យឧបករណ៍បំលែងសៀគ្វីពីរសម្រាប់គម្រោងប្តូរឧបករណ៍ 15kV របស់អ្នក។ ទាំងពីរបង្ហាញពីកម្រិតវ៉ុលរហូតដល់ 690V ។ ទាំងពីររាយសមត្ថភាពបំបែកដ៏គួរឱ្យចាប់អារម្មណ៍។ នៅលើក្រដាស ពួកវាមើលទៅអាចផ្លាស់ប្តូរគ្នាបាន។.

ពួកវាមិនមែនទេ។.

ជ្រើសរើសខុស—ដំឡើងឧបករណ៍បំលែងសៀគ្វីខ្យល់ (ACB) កន្លែងដែលអ្នកត្រូវការឧបករណ៍បំលែងសៀគ្វីខ្វះចន្លោះ (VCB) ឬផ្ទុយមកវិញ—ហើយអ្នកមិនត្រឹមតែបំពានស្តង់ដារ IEC ប៉ុណ្ណោះទេ។ អ្នកកំពុងលេងល្បែងជាមួយនឹងហានិភ័យនៃពន្លឺផ្លេកបន្ទោរ ថវិកាថែទាំ និងអាយុកាលឧបករណ៍។ ភាពខុសគ្នាពិតប្រាកដមិនមាននៅក្នុងខិត្តប័ណ្ណទីផ្សារទេ។ វាស្ថិតនៅក្នុងរូបវិទ្យានៃរបៀបដែលឧបករណ៍បំលែងនីមួយៗពន្លត់ធ្នូអគ្គិសនី ហើយរូបវិទ្យានោះដាក់កម្រិតយ៉ាងខ្លាំង ពិដានវ៉ុល ដែលការបដិសេធសន្លឹកទិន្នន័យមិនអាចជំនួសបានទេ។.

នេះជាអ្វីដែលពិតជាបំបែក ACBs ពី VCBs—និងរបៀបជ្រើសរើសមួយដែលត្រឹមត្រូវសម្រាប់ប្រព័ន្ធរបស់អ្នក។.

ចម្លើយរហ័ស៖ ACB ទល់នឹង VCB មួយភ្លែត

ភាពខុសគ្នាស្នូល៖ ឧបករណ៍បំលែងសៀគ្វីខ្យល់ (ACBs) ពន្លត់ធ្នូអគ្គិសនីនៅក្នុងខ្យល់បរិយាកាស ហើយត្រូវបានរចនាឡើងសម្រាប់ ប្រព័ន្ធវ៉ុលទាបរហូតដល់ 1,000V AC (គ្រប់គ្រងដោយ IEC 60947-2:2024)។ ឧបករណ៍បំលែងសៀគ្វីខ្វះចន្លោះ (VCBs) ពន្លត់ធ្នូនៅក្នុងបរិយាកាសខ្វះចន្លោះដែលបានផ្សាភ្ជាប់ ហើយដំណើរការនៅក្នុង ប្រព័ន្ធវ៉ុលមធ្យមពី 11kV ដល់ 33kV (គ្រប់គ្រងដោយ IEC 62271-100:2021)។ ការបំបែកវ៉ុលនេះមិនមែនជាជម្រើសផ្នែកផលិតផលទេ—វាត្រូវបានកំណត់ដោយរូបវិទ្យានៃការរំខានធ្នូ។.

នេះជារបៀបដែលពួកវាប្រៀបធៀបទូទាំងលក្ខណៈបច្ចេកទេសសំខាន់ៗ៖

| ការបញ្ជាក់ | ឧបករណ៍បំបែកសៀគ្វីខ្យល់ (ACB) | ឧបករណ៍បំលែងសៀគ្វីខ្វះចន្លោះ (VCB) |

| ជួរវ៉ុល | វ៉ុលទាប៖ 400V ទៅ 1,000V AC | វ៉ុលមធ្យម៖ 11kV ទៅ 33kV (ខ្លះ 1kV-38kV) |

| ជួរបច្ចុប្បន្ន | ចរន្តខ្ពស់៖ 800A ទៅ 10,000A | ចរន្តមធ្យម៖ 600A ទៅ 4,000A |

| សមត្ថភាពបំបែក | រហូតដល់ 100kA នៅ 690V | 25kA ទៅ 50kA នៅ MV |

| មធ្យមពន្លត់ធ្នូ | ខ្យល់នៅសម្ពាធបរិយាកាស | ខ្វះចន្លោះ (10^-2 ទៅ 10^-6 torr) |

| យន្តការប្រតិបត្តិការ | បំពង់បង្ហូរធ្នូពង្រីក និងធ្វើឱ្យធ្នូត្រជាក់ | ឧបករណ៍រំខានខ្វះចន្លោះដែលបានផ្សាភ្ជាប់ពន្លត់ធ្នូនៅសូន្យចរន្តដំបូង |

| ប្រេកង់ថែទាំ | រៀងរាល់ 6 ខែម្តង (ពីរដងក្នុងមួយឆ្នាំ) | រៀងរាល់ 3 ទៅ 5 ឆ្នាំ |

| អាយុកាលទំនាក់ទំនង | 3 ទៅ 5 ឆ្នាំ (ការប៉ះពាល់ខ្យល់បណ្តាលឱ្យមានសំណឹក) | 20 ទៅ 30 ឆ្នាំ (បរិយាកាសបិទជិត) |

| កម្មវិធីធម្មតា។ | ការចែកចាយ LV, MCCs, PCCs, បន្ទះពាណិជ្ជកម្ម/ឧស្សាហកម្ម | ឧបករណ៍ប្តូរ MV, ស្ថានីយរងឧបករណ៍ប្រើប្រាស់, ការការពារម៉ូទ័រ HV |

| ស្តង់ដារ IEC | IEC 60947-2:2024 (≤1000V AC) | IEC 62271-100:2021+A1:2024 (>1000V) |

| ថ្លៃដើម | ទាបជាង ($8K-$15K ធម្មតា) | ខ្ពស់ជាង ($20K-$30K ធម្មតា) |

| ការចំណាយសរុប 15 ឆ្នាំ | ~$48K (ជាមួយនឹងការថែទាំ) | ~$24K (ការថែទាំតិចតួចបំផុត) |

កត់សម្គាល់បន្ទាត់បែងចែកស្អាតនៅ 1,000V? នោះហើយជា ការបំបែកស្តង់ដារ—ហើយវាមាន ពីព្រោះលើសពី 1kV ខ្យល់មិនអាចពន្លត់ធ្នូបានលឿនគ្រប់គ្រាន់ទេ។ រូបវិទ្យាកំណត់ព្រំដែន; IEC គ្រាន់តែសរសេរកូដវាប៉ុណ្ណោះ។.

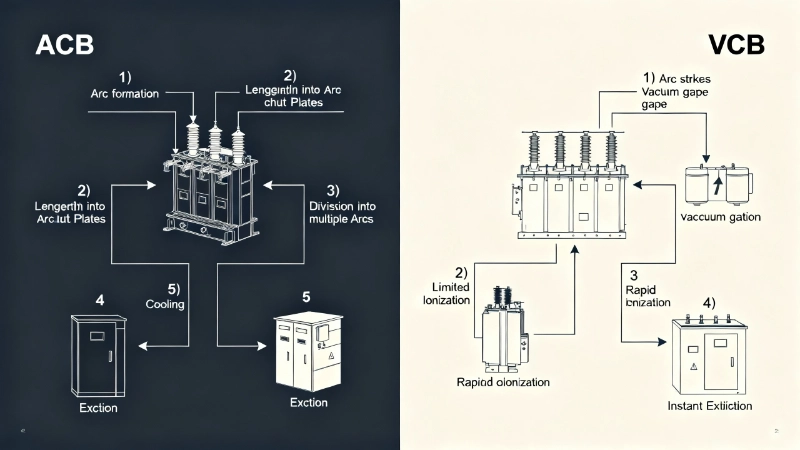

រូបភាពទី 1៖ ការប្រៀបធៀបរចនាសម្ព័ន្ធនៃបច្ចេកវិទ្យា ACB និង VCB ។ ACB (ខាងឆ្វេង) ប្រើបំពង់បង្ហូរធ្នូនៅក្នុងខ្យល់បើកចំហ ខណៈពេលដែល VCB (ខាងស្តាំ) ប្រើឧបករណ៍រំខានខ្វះចន្លោះដែលបានផ្សាភ្ជាប់សម្រាប់ការផុតពូជធ្នូ។.

ការពន្លត់ធ្នូ៖ ខ្យល់ទល់នឹងខ្វះចន្លោះ (ហេតុអ្វីបានជារូបវិទ្យាកំណត់ពិដានវ៉ុល)

នៅពេលអ្នកបំបែកទំនាក់ទំនងដែលផ្ទុកចរន្តនៅក្រោមបន្ទុក ធ្នូនឹងបង្កើត។ ជានិច្ច។ ធ្នូនោះគឺជាជួរឈរផ្លាស្មា—ឧស្ម័នអ៊ីយ៉ូដដែលដឹកនាំរាប់ពាន់អំពែរនៅសីតុណ្ហភាពឡើងដល់ 20,000°C (ក្តៅជាងផ្ទៃព្រះអាទិត្យ)។ ការងាររបស់ឧបករណ៍បំលែងសៀគ្វីរបស់អ្នកគឺដើម្បីពន្លត់ធ្នូនោះ មុនពេលវាផ្សារភ្ជាប់ទំនាក់ទំនងជាមួយគ្នា ឬបង្កឱ្យមានព្រឹត្តិការណ៍ពន្លឺផ្លេកបន្ទោរ។.

របៀបដែលវាធ្វើនោះគឺអាស្រ័យទាំងស្រុងលើមធ្យមដែលនៅជុំវិញទំនាក់ទំនង។.

របៀបដែល ACBs ប្រើខ្យល់ និងបំពង់បង្ហូរធ្នូ

ក ខ្យគ្វីល្មើស រំខានធ្នូនៅក្នុងខ្យល់បរិយាកាស។ ទំនាក់ទំនងរបស់ឧបករណ៍បំលែងត្រូវបានដាក់នៅក្នុងបំពង់បង្ហូរធ្នូ—អារេនៃបន្ទះដែកដែលដាក់ទីតាំងដើម្បីស្ទាក់ចាប់ធ្នូនៅពេលដែលទំនាក់ទំនងដាច់ពីគ្នា។ នេះគឺជាលំដាប់៖

- ការបង្កើតធ្នូ៖ ទំនាក់ទំនងដាច់ពីគ្នា ធ្នូកូដកម្មនៅក្នុងខ្យល់

- ការពន្លូតធ្នូ៖ កម្លាំងម៉ាញេទិកជំរុញធ្នូទៅក្នុងបំពង់បង្ហូរធ្នូ

- ការបែងចែកធ្នូ៖ បន្ទះដែករបស់បំពង់បង្ហូរបំបែកធ្នូទៅជាធ្នូតូចៗជាច្រើន

- ការត្រជាក់ធ្នូ៖ ផ្ទៃដីកើនឡើង និងការប៉ះពាល់ខ្យល់ធ្វើឱ្យផ្លាស្មាត្រជាក់

- ការផុតពូជធ្នូ៖ នៅពេលដែលធ្នូត្រជាក់ និងពន្លូត ភាពធន់កើនឡើងរហូតដល់ធ្នូមិនអាចទ្រទ្រង់ខ្លួនឯងនៅសូន្យចរន្តបន្ទាប់បានទៀតទេ

នេះដំណើរការដោយភាពជឿជាក់រហូតដល់ប្រហែល 1,000V ។ លើសពីវ៉ុលនោះ ថាមពលរបស់ធ្នូគឺខ្លាំងពេក។ កម្លាំង dielectric របស់ខ្យល់ (ជម្រាលវ៉ុលដែលវាអាចទប់ទល់មុនពេលបំបែក) គឺប្រហែល 3 kV/mm នៅសម្ពាធបរិយាកាស។ នៅពេលដែលវ៉ុលប្រព័ន្ធឡើងចូលទៅក្នុងជួរពហុគីឡូវ៉ុល ធ្នូគ្រាន់តែវាយប្រហារម្តងទៀតនៅទូទាំងគម្លាតទំនាក់ទំនងដែលកំពុងពង្រីក។ អ្នកមិនអាចសាងសង់បំពង់បង្ហូរធ្នូបានយូរគ្រប់គ្រាន់ដើម្បីបញ្ឈប់វាដោយមិនធ្វើឱ្យឧបករណ៍បំលែងមានទំហំប៉ុនឡានតូចនោះទេ។.

នោះហើយជា ពិដានវ៉ុល.

របៀបដែល VCBs ប្រើរូបវិទ្យាខ្វះចន្លោះ

មួយ ឧបករណ៍បំបែកសៀគ្វីបូមធូលី ចាត់វិធានការខុសគ្នាទាំងស្រុង។ ទំនាក់ទំនងត្រូវបានបិទនៅក្នុងឧបករណ៍រំខានខ្វះចន្លោះដែលបានផ្សាភ្ជាប់—បន្ទប់មួយដែលត្រូវបានជម្លៀសទៅសម្ពាធចន្លោះពី 10^-2 ទៅ 10^-6 torr (នោះគឺប្រហែលមួយលាននៃសម្ពាធបរិយាកាស)។.

នៅពេលដែលទំនាក់ទំនងដាច់ពីគ្នាក្រោមបន្ទុក៖

- ការបង្កើតធ្នូ៖ ធ្នូកូដកម្មនៅក្នុងគម្លាតខ្វះចន្លោះ

- អ៊ីយ៉ូដកម្មកំណត់៖ ដោយសារស្ទើរតែគ្មានម៉ូលេគុលឧស្ម័ន ធ្នូអគ្គិសនីខ្វះមធ្យោបាយទ្រទ្រង់

- ការបន្សាបអ៊ីយ៉ុងយ៉ាងឆាប់រហ័ស៖ នៅពេលសូន្យចរន្តធម្មជាតិដំបូង (រាល់ពាក់កណ្តាលវដ្តនៅក្នុង AC) មិនមានអ្នកផ្ទុកបន្ទុកគ្រប់គ្រាន់ដើម្បីបង្កើតធ្នូអគ្គិសនីឡើងវិញទេ។

- ការពន្លត់ភ្លាមៗ៖ ធ្នូអគ្គិសនីរលត់ក្នុងមួយវដ្ត (8.3 មីលីវិនាទីលើប្រព័ន្ធ 60 Hz)

ម៉ាស៊ីនបូមធូលីផ្តល់នូវគុណសម្បត្តិដ៏ធំពីរ។ ទីមួយ, កម្លាំង dielectric៖គម្លាតខ្វះចន្លោះត្រឹមតែ 10mm អាចទប់ទល់នឹងវ៉ុលរហូតដល់ 40kV — ខ្លាំងជាងខ្យល់ 10 ទៅ 100 ដងនៅចម្ងាយគម្លាតដូចគ្នា។ ទីពីរ, ការថែរក្សាទំនាក់ទំនង៖ដោយសារមិនមានអុកស៊ីហ្សែន ទំនាក់ទំនងមិនកត់សុី ឬសឹករេចរឹលក្នុងអត្រាដូចគ្នានឹងទំនាក់ទំនង ACB ដែលប៉ះពាល់នឹងខ្យល់នោះទេ។ នោះហើយជា គុណសម្បត្តិនៃការផ្សាភ្ជាប់សម្រាប់អាយុកាល.

ទំនាក់ទំនង VCB នៅក្នុងឧបករណ៍បំបែកដែលបានថែទាំត្រឹមត្រូវអាចមានរយៈពេល 20 ទៅ 30 ឆ្នាំ។ ទំនាក់ទំនង ACB ដែលប៉ះពាល់នឹងអុកស៊ីហ្សែនក្នុងបរិយាកាស និងផ្លាស្មាធ្នូ? អ្នកកំពុងមើលការជំនួសរៀងរាល់ 3 ទៅ 5 ឆ្នាំម្តង ជួនកាលឆាប់ជាងនេះនៅក្នុងបរិយាកាសដែលមានធូលី ឬសំណើម។.

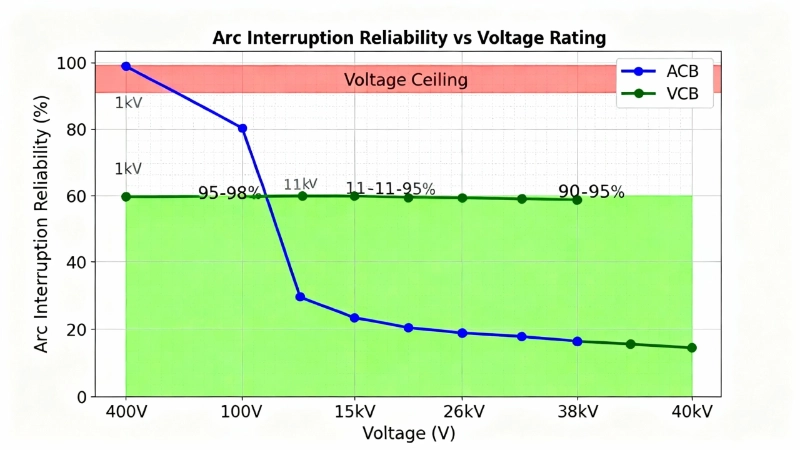

រូបភាពទី 2៖ យន្តការពន្លត់ធ្នូ។ ACB តម្រូវឱ្យមានជំហានជាច្រើនដើម្បីពង្រីក ចែក និងធ្វើឱ្យធ្នូត្រជាក់នៅក្នុងខ្យល់ (ខាងឆ្វេង) ខណៈពេលដែល VCB ពន្លត់ធ្នូភ្លាមៗនៅសូន្យចរន្តដំបូងដោយសារតែកម្លាំង dielectric ដ៏ល្អឥតខ្ចោះនៃម៉ាស៊ីនបូមធូលី (ខាងស្តាំ)។.

គាំទ្រទិព្វ#១៖ ពិដានវ៉ុលមិនអាចចរចាបានទេ។ ACBs មិនមានសមត្ថភាពខាងរូបវន្តក្នុងការរំខានធ្នូដោយភាពជឿជាក់លើសពី 1kV នៅក្នុងខ្យល់នៅសម្ពាធបរិយាកាស។ ប្រសិនបើវ៉ុលប្រព័ន្ធរបស់អ្នកលើសពី 1,000V AC អ្នកត្រូវការ VCB — មិនមែនជាជម្រើស “ល្អជាង” នោះទេ ប៉ុន្តែជាជម្រើសតែមួយគត់ដែលអនុលោមតាមរូបវិទ្យា និងស្តង់ដារ IEC ។.

ការវាយតម្លៃវ៉ុល និងចរន្ត៖ អ្វីដែលលេខពិតជាមានន័យ

វ៉ុលមិនមែនគ្រាន់តែជាបន្ទាត់បញ្ជាក់នៅលើសន្លឹកទិន្នន័យនោះទេ។ វាជាលក្ខណៈវិនិច្ឆ័យនៃការជ្រើសរើសជាមូលដ្ឋានដែលកំណត់ប្រភេទឧបករណ៍បំបែកដែលអ្នកអាចពិចារណាបាន។ ការវាយតម្លៃបច្ចុប្បន្នមានសារៈសំខាន់ ប៉ុន្តែវាមកទីពីរ។.

នេះជាអ្វីដែលលេខមានន័យក្នុងការអនុវត្ត។.

ការវាយតម្លៃ ACB៖ ចរន្តខ្ពស់ វ៉ុលទាប

ពិដានវ៉ុល៖ ACBs ដំណើរការដោយភាពជឿជាក់ពី 400V ដល់ 1,000V AC (ជាមួយនឹងការរចនាឯកទេសមួយចំនួនដែលត្រូវបានវាយតម្លៃដល់ 1,500V DC)។ ចំណុចផ្អែមធម្មតាគឺ 400V ឬ 690V សម្រាប់ប្រព័ន្ធឧស្សាហកម្មបីដំណាក់កាល។ ខាងលើ 1kV AC លក្ខណៈសម្បត្តិនៃ dielectric របស់ខ្យល់ធ្វើឱ្យការរំខានធ្នូដែលអាចទុកចិត្តបានមិនជាក់ស្តែង — នោះ ពិដានវ៉ុល ដែលយើងបានពិភាក្សាមិនមែនជាដែនកំណត់នៃការរចនានោះទេ។ វាជាព្រំដែនរាងកាយ។.

សមត្ថភាពបច្ចុប្បន្ន៖ កន្លែងដែល ACBs គ្របដណ្តប់គឺការគ្រប់គ្រងបច្ចុប្បន្ន។ ការវាយតម្លៃមានចាប់ពី 800A សម្រាប់បន្ទះចែកចាយតូចជាងរហូតដល់ 10,000A សម្រាប់ការអនុវត្តច្រកចូលសេវាកម្មសំខាន់។ សមត្ថភាពចរន្តខ្ពស់នៅវ៉ុលទាប គឺជាអ្វីដែលការចែកចាយវ៉ុលទាបត្រូវការយ៉ាងជាក់លាក់ — គិតពីមជ្ឈមណ្ឌលគ្រប់គ្រងម៉ូទ័រ (MCCs) មជ្ឈមណ្ឌលគ្រប់គ្រងថាមពល (PCCs) និងក្តារចែកចាយសំខាន់ៗនៅក្នុងកន្លែងពាណិជ្ជកម្ម និងឧស្សាហកម្ម។.

សមត្ថភាពបំបែក៖ ការវាយតម្លៃរំខានសៀគ្វីខ្លីឈានដល់រហូតដល់ 100kA នៅ 690V ។ នោះស្តាប់ទៅគួរអោយចាប់អារម្មណ៍ — ហើយវាគឺសម្រាប់ការអនុវត្តវ៉ុលទាប។ ប៉ុន្តែសូមដាក់វានៅក្នុងទស្សនៈជាមួយនឹងការគណនាថាមពល៖

- សមត្ថភាពបំបែក៖ 100kA នៅ 690V (បន្ទាត់ទៅបន្ទាត់)

- ថាមពលជាក់ស្តែង៖ √3 × 690V × 100kA ≈ 119 MVA

នោះគឺជាថាមពលកំហុសអតិបរមាដែល ACB អាចរំខានដោយសុវត្ថិភាព។ សម្រាប់រោងចក្រឧស្សាហកម្ម 400V/690V ជាមួយនឹងឧបករណ៍បំលែង 1.5 MVA និងសមាមាត្រ X/R ធម្មតា ឧបករណ៍បំបែក 65kA គឺគ្រប់គ្រាន់ហើយ។ ឯកតា 100kA ត្រូវបានបម្រុងទុកសម្រាប់ការចែកចាយវ៉ុលទាបខ្នាតឧបករណ៍ប្រើប្រាស់ ឬកន្លែងដែលមានឧបករណ៍បំលែងធំៗជាច្រើនស្របគ្នា។.

កម្មវិធីធម្មតា៖

- បន្ទះចែកចាយសំខាន់វ៉ុលទាប (LVMDP)

- មជ្ឈមណ្ឌលគ្រប់គ្រងម៉ូទ័រ (MCCs) សម្រាប់ស្នប់ ម៉ាស៊ីនផ្លុំ ខ្យល់

- មជ្ឈមណ្ឌលគ្រប់គ្រងថាមពល (PCCs) សម្រាប់គ្រឿងម៉ាស៊ីនឧស្សាហកម្ម

- ការការពារម៉ាស៊ីនភ្លើង និងបន្ទះធ្វើសមកាលកម្ម

- បន្ទប់អគ្គិសនីអាគារពាណិជ្ជកម្ម (ក្រោម 1kV)

ការវាយតម្លៃ VCB៖ វ៉ុលមធ្យម ចរន្តល្មម

ជួរវ៉ុល៖ VCB ត្រូវបានរចនាឡើងសម្រាប់ប្រព័ន្ធវ៉ុលមធ្យម ជាធម្មតាពី 11kV ដល់ 33kV ។ ការរចនាមួយចំនួនពង្រីកជួរចុះក្រោមដល់ 1kV ឬរហូតដល់ 38kV (វិសោធនកម្មឆ្នាំ 2024 នៃ IEC 62271-100 បានបន្ថែមការវាយតម្លៃស្តង់ដារនៅ 15.5kV, 27kV និង 40.5kV) ។ កម្លាំង dielectric ដ៏ល្អឥតខ្ចោះនៃឧបករណ៍រំខានម៉ាស៊ីនបូមធូលីដែលបានផ្សាភ្ជាប់ធ្វើឱ្យកម្រិតវ៉ុលទាំងនេះអាចគ្រប់គ្រងបានក្នុងស្នាមតូចមួយ។.

សមត្ថភាពបច្ចុប្បន្ន៖ VCB គ្រប់គ្រងចរន្តល្មមបើប្រៀបធៀបទៅនឹង ACBs ជាមួយនឹងការវាយតម្លៃធម្មតាពី 600A ដល់ 4,000A ។ នេះគឺគ្រប់គ្រាន់សម្រាប់កម្មវិធីវ៉ុលមធ្យម។ ឧបករណ៍បំបែក 2,000A នៅ 11kV អាចផ្ទុកបន្ទុកបន្ត 38 MVA — ស្មើនឹងម៉ូទ័រឧស្សាហកម្មធំៗរាប់សិប ឬតម្រូវការថាមពលរបស់រោងចក្រឧស្សាហកម្មទំហំមធ្យមទាំងមូល។.

សមត្ថភាពបំបែក៖ VCB ត្រូវបានវាយតម្លៃពី 25kA ដល់ 50kA នៅកម្រិតវ៉ុលរៀងៗខ្លួន។ សូមដំណើរការការគណនាថាមពលដូចគ្នាសម្រាប់ VCB 50kA នៅ 33kV៖

- សមត្ថភាពបំបែក៖ 50kA នៅ 33kV (បន្ទាត់ទៅបន្ទាត់)

- ថាមពលជាក់ស្តែង៖ √3 × 33kV × 50kA ≈ 2,850 MVA

នោះហើយជា ថាមពលរំខានច្រើនជាង 24 ដង ជាង ACB 100kA របស់យើងនៅ 690V ។ ភ្លាមៗនោះ សមត្ថភាពបំបែក 50kA “ទាបជាង” នោះមើលទៅមិនសមរម្យទេ។ VCB កំពុងរំខានចរន្តកំហុសនៅកម្រិតថាមពលដែលនឹងហួតបំពង់បង្ហូរធ្នូរបស់ ACB ។.

រូបភាពទី 3៖ ការមើលឃើញពិដានវ៉ុល។ ACBs ដំណើរការដោយភាពជឿជាក់រហូតដល់ 1,000V ប៉ុន្តែមិនអាចរំខានធ្នូដោយសុវត្ថិភាពលើសពីកម្រិតនេះ (តំបន់ក្រហម) ខណៈពេលដែល VCB គ្របដណ្តប់លើជួរវ៉ុលមធ្យមពី 11kV ដល់ 38kV (តំបន់បៃតង)។.

កម្មវិធីធម្មតា៖

- ស្ថានីយ៍បំប្លែងការចែកចាយឧបករណ៍ប្រើប្រាស់ (11kV, 22kV, 33kV)

- ឧបករណ៍ប្តូរវ៉ុលមធ្យមឧស្សាហកម្ម (អង្គភាពចិញ្ចៀនសំខាន់ៗ បន្ទះប្តូរ)

- ការការពារម៉ូទ័រ induction វ៉ុលខ្ពស់ (>1,000 HP)

- ការការពារបឋមរបស់ Transformer

- កន្លែងផលិតថាមពល (ឧបករណ៍បំបែកសៀគ្វីម៉ាស៊ីនភ្លើង)

- ប្រព័ន្ធថាមពលកកើតឡើងវិញ (កសិដ្ឋានខ្យល់ ស្ថានីយ៍ Inverter សូឡា)

គាំទ្រទិព្វ#២៖ កុំប្រៀបធៀបសមត្ថភាពបំបែកជាគីឡូអំពែរតែម្នាក់ឯង។ គណនាថាមពលរំខាន MVA (√3 × វ៉ុល × ចរន្ត) ។ VCB 50kA នៅ 33kV រំខានថាមពលច្រើនជាង ACB 100kA នៅ 690V ។ វ៉ុលមានសារៈសំខាន់ជាងចរន្តនៅពេលវាយតម្លៃសមត្ថភាពឧបករណ៍បំបែក។.

ការបំបែកស្តង់ដារ៖ IEC 60947-2 (ACB) ទល់នឹង IEC 62271-100 (VCB)

គណៈកម្មការអេឡិចត្រូតបច្ចេកទេសអន្តរជាតិ (IEC) មិនបែងចែកស្តង់ដារដោយចៃដន្យទេ។ នៅពេលដែល IEC 60947-2 គ្រប់គ្រងឧបករណ៍បំបែករហូតដល់ 1,000V ហើយ IEC 62271-100 ចូលកាន់កាប់លើសពី 1,000V ព្រំដែននោះឆ្លុះបញ្ចាំងពីការពិតរាងកាយដែលយើងបានពិភាក្សា។ នេះគឺជា ការបំបែកស្តង់ដារ, ហើយវាជាត្រីវិស័យរចនារបស់អ្នក។.

IEC 60947-2:2024 សម្រាប់ឧបករណ៍បំបែកសៀគ្វីខ្យល់

វិសាលភាព៖ ស្តង់ដារនេះអនុវត្តចំពោះឧបករណ៍បំបែកសៀគ្វីដែលមានវ៉ុលដែលបានវាយតម្លៃ មិនលើសពី 1,000V AC ឬ 1,500V DC. វាជាឯកសារយោងដែលមានសិទ្ធិអំណាចសម្រាប់ការការពារសៀគ្វីវ៉ុលទាប រួមទាំង ACBs ឧបករណ៍បំបែកសៀគ្វីករណីដែលបានដំឡើង (MCCBs) និងឧបករណ៍បំបែកសៀគ្វីខ្នាតតូច (MCBs)។.

ការបោះពុម្ពលើកទីប្រាំមួយត្រូវបានបោះពុម្ពនៅក្នុង ខែកញ្ញា ឆ្នាំ 2024, ដោយជំនួសការបោះពុម្ពឆ្នាំ 2016 ។ ការធ្វើបច្ចុប្បន្នភាពសំខាន់ៗរួមមាន៖

- ភាពសមស្របសម្រាប់ការ अलगाव៖ បានបញ្ជាក់តម្រូវការសម្រាប់ការប្រើប្រាស់ឧបករណ៍ផ្តាច់សៀគ្វីជាកុងតាក់ដាច់ចរន្ត

- ការដកចំណាត់ថ្នាក់ចេញ៖ IEC បានលុបចោលចំណាត់ថ្នាក់នៃឧបករណ៍ផ្តាច់សៀគ្វីតាមរយៈមធ្យមរំខាន (ខ្យល់ ប្រេង SF6 ។ល។)។ ហេតុអ្វី? ពីព្រោះ វ៉ុលបានប្រាប់អ្នករួចហើយអំពីមធ្យម. ។ ប្រសិនបើអ្នកនៅ 690V អ្នកកំពុងប្រើខ្យល់ ឬប្រអប់ផ្សិតបិទជិត។ ប្រព័ន្ធចំណាត់ថ្នាក់ចាស់គឺលើសលប់។.

- ការកែតម្រូវឧបករណ៍ខាងក្រៅ៖ ប្បញ្ញត្តិថ្មីសម្រាប់ការកែតម្រូវការកំណត់ចរន្តលើសតាមរយៈឧបករណ៍ខាងក្រៅ

- ការធ្វើតេស្តដែលបានពង្រឹង៖ បានបន្ថែមការធ្វើតេស្តសម្រាប់ការបញ្ចេញកំហុសដី និងលក្ខណៈសម្បត្តិ dielectric នៅក្នុងទីតាំងដែលបានផ្តាច់

- ភាពប្រសើរឡើងនៃ EMC៖ បានធ្វើបច្ចុប្បន្នភាពនីតិវិធីធ្វើតេស្តភាពឆបគ្នានៃអេឡិចត្រូម៉ាញ៉េទិក (EMC) និងវិធីសាស្ត្រវាស់ស្ទង់ការបាត់បង់ថាមពល

ការកែប្រែឆ្នាំ 2024 ធ្វើឱ្យស្តង់ដារកាន់តែស្អាត និងស្របតាមអង្គភាពធ្វើដំណើរឌីជីថលទំនើប និងបច្ចេកវិទ្យាឧបករណ៍ផ្តាច់សៀគ្វីឆ្លាតវៃ ប៉ុន្តែព្រំដែនវ៉ុលស្នូល—≤1,000V AC—នៅតែមិនផ្លាស់ប្តូរ។ ខាងលើនេះ អ្នកនៅក្រៅដែនសមត្ថកិច្ចរបស់ IEC 60947-2។.

IEC 62271-100:2021 (វិសោធនកម្ម 1: 2024) សម្រាប់ឧបករណ៍ផ្តាច់សៀគ្វីខ្វះចន្លោះ

វិសាលភាព៖ ស្តង់ដារនេះគ្រប់គ្រងឧបករណ៍ផ្តាច់សៀគ្វីចរន្តឆ្លាស់ដែលត្រូវបានរចនាឡើងសម្រាប់ ប្រព័ន្ធបីដំណាក់កាលដែលមានវ៉ុលលើសពី 1,000V. ។ វាត្រូវបានកែសម្រួលជាពិសេសសម្រាប់ឧបករណ៍ប្តូរក្នុងផ្ទះ និងក្រៅផ្ទះដែលមានវ៉ុលមធ្យម និងវ៉ុលខ្ពស់ ដែល VCBs គឺជាបច្ចេកវិទ្យាលេចធ្លោ (រួមជាមួយឧបករណ៍ផ្តាច់ SF6 សម្រាប់ថ្នាក់វ៉ុលខ្ពស់បំផុត)។.

ការបោះពុម្ពលើកទីបីត្រូវបានបោះពុម្ពនៅឆ្នាំ 2021 ជាមួយនឹង វិសោធនកម្ម 1 បានចេញផ្សាយនៅខែសីហា ឆ្នាំ 2024. ។ ការធ្វើបច្ចុប្បន្នភាពថ្មីៗរួមមាន៖

- តម្លៃ TRV (Transient Recovery Voltage) ដែលបានធ្វើបច្ចុប្បន្នភាព៖ គណនាប៉ារ៉ាម៉ែត្រ TRV ឡើងវិញក្នុងតារាងជាច្រើន ដើម្បីឆ្លុះបញ្ចាំងពីឥរិយាបថប្រព័ន្ធជាក់ស្តែង និងការរចនាឧបករណ៍បំលែងថ្មីជាងមុន

- វ៉ុលដែលបានវាយតម្លៃថ្មី៖ ការវាយតម្លៃស្តង់ដារត្រូវបានបន្ថែមនៅ 15.5kV, 27kV និង 40.5kV ដើម្បីគ្របដណ្តប់វ៉ុលប្រព័ន្ធក្នុងតំបន់ (ជាពិសេសនៅអាស៊ី និងមជ្ឈិមបូព៌ា)

- និយមន័យកំហុសស្ថានីយដែលបានកែប្រែ៖ បានបញ្ជាក់ពីអ្វីដែលបង្កើតជាកំហុសស្ថានីយសម្រាប់គោលបំណងធ្វើតេស្ត

- លក្ខណៈវិនិច្ឆ័យនៃការធ្វើតេស្ត Dielectric៖ បានបន្ថែមលក្ខណៈវិនិច្ឆ័យសម្រាប់ការធ្វើតេស្ត dielectric; បានបញ្ជាក់យ៉ាងច្បាស់ថាការធ្វើតេស្តការឆក់ដោយផ្នែកអនុវត្តតែចំពោះ GIS (Gas-Insulated Switchgear) និងឧបករណ៍ផ្តាច់ធុងស្លាប់ មិនមែន VCBs ធម្មតានោះទេ។

- ការពិចារណាបរិស្ថាន៖ ការណែនាំដែលបានពង្រឹងលើកត្តាកម្ពស់ ការបំពុល និងការកាត់បន្ថយសីតុណ្ហភាព

វិសោធនកម្មឆ្នាំ 2024 រក្សាស្តង់ដារបច្ចុប្បន្នជាមួយនឹងការផ្លាស់ប្តូរហេដ្ឋារចនាសម្ព័ន្ធបណ្តាញសកល ប៉ុន្តែគោលការណ៍គ្រឹះនៅតែមាន៖ ខាងលើ 1,000V អ្នកត្រូវការឧបករណ៍ផ្តាច់វ៉ុលមធ្យម, ហើយសម្រាប់ជួរ 1kV-38kV នោះស្ទើរតែតែងតែមានន័យថា VCB ។.

ហេតុអ្វីបានជាស្តង់ដារទាំងនេះមិនត្រួតស៊ីគ្នា

ព្រំដែន 1,000V មិនមែនជាបំពានទេ។ វាជាចំណុចដែលខ្យល់បរិយាកាសផ្លាស់ប្តូរពី “មធ្យមពន្លត់ធ្នូគ្រប់គ្រាន់” ទៅជា “ការទទួលខុសត្រូវ” ។ IEC មិនបានបង្កើតស្តង់ដារពីរដើម្បីលក់សៀវភៅបន្ថែមទេ។ ពួកគេបានធ្វើឱ្យមានលក្ខណៈជាផ្លូវការនូវការពិតផ្នែកវិស្វកម្ម៖

- ខាងក្រោម 1kV៖ ការរចនាដោយផ្អែកលើខ្យល់ ឬប្រអប់ផ្សិតដំណើរការ។ ផ្លូវរូងក្រោមដីធ្នូមានប្រសិទ្ធភាព។ ឧបករណ៍ផ្តាច់មានទំហំតូច និងសន្សំសំចៃ។.

- ខាងលើ 1kV៖ ខ្យល់តម្រូវឱ្យមានផ្លូវរូងក្រោមដីធ្នំធំដែលមិនអាចអនុវត្តបាន។ ខ្វះចន្លោះ (ឬ SF6 សម្រាប់វ៉ុលខ្ពស់ជាង) ក្លាយជាចាំបាច់សម្រាប់ការរំខានធ្នូដោយសុវត្ថិភាព និងអាចទុកចិត្តបាននៅក្នុងស្នាមជើងសមហេតុផល។.

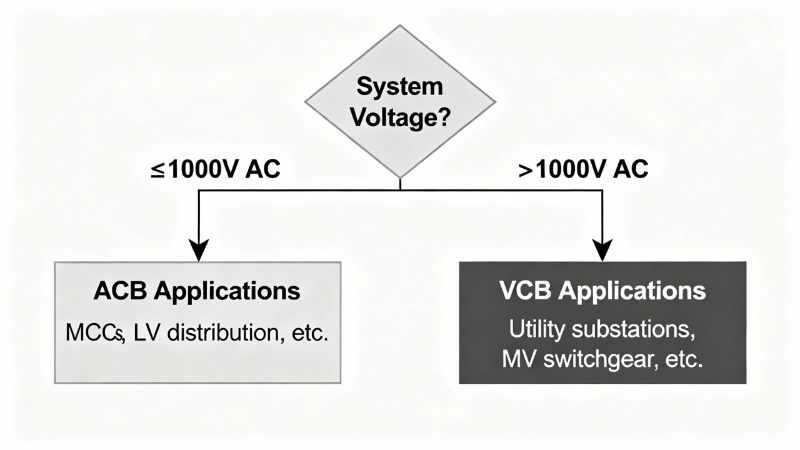

នៅពេលដែលអ្នកកំពុងបញ្ជាក់ឧបករណ៍ផ្តាច់ សំណួរដំបូងមិនមែនជា “ACB ឬ VCB?” ទេ។ វាគឺ “តើវ៉ុលប្រព័ន្ធរបស់ខ្ញុំគឺជាអ្វី?” ចម្លើយនោះចង្អុលអ្នកទៅស្តង់ដារត្រឹមត្រូវ ដែលចង្អុលអ្នកទៅប្រភេទឧបករណ៍ផ្តាច់ត្រឹមត្រូវ។.

គាំទ្រទិព្វ#៣៖ នៅពេលពិនិត្យមើលសន្លឹកទិន្នន័យឧបករណ៍ផ្តាច់សៀគ្វី សូមពិនិត្យមើលថាតើស្តង់ដារ IEC មួយណាដែលវាអនុលោមតាម។ ប្រសិនបើវាចុះបញ្ជី IEC 60947-2 វាគឺជាឧបករណ៍ផ្តាច់វ៉ុលទាប (≤1kV)។ ប្រសិនបើវាចុះបញ្ជី IEC 62271-100 វាគឺជាឧបករណ៍ផ្តាច់វ៉ុលមធ្យម/ខ្ពស់ (>1kV)។ ការអនុលោមតាមស្តង់ដារប្រាប់អ្នកពីថ្នាក់វ៉ុលភ្លាមៗ។.

កម្មវិធី៖ ការផ្គូផ្គងប្រភេទឧបករណ៍ផ្តាច់ទៅនឹងប្រព័ន្ធរបស់អ្នក

ការជ្រើសរើសរវាង ACB និង VCB មិនមែននិយាយអំពីចំណូលចិត្តទេ។ វាគឺអំពីការផ្គូផ្គងសមត្ថភាពរាងកាយរបស់ឧបករណ៍ផ្តាច់ទៅនឹងលក្ខណៈអគ្គិសនី និងតម្រូវការប្រតិបត្តិការរបស់ប្រព័ន្ធអ្នក។.

នេះជារបៀបគូសផែនទីប្រភេទឧបករណ៍ផ្តាច់ទៅកម្មវិធី។.

ពេលណាត្រូវប្រើ ACBs

ឧបករណ៍ផ្តាច់សៀគ្វីខ្យល់គឺជាជម្រើសត្រឹមត្រូវសម្រាប់ ប្រព័ន្ធចែកចាយវ៉ុលទាប ដែលសមត្ថភាពចរន្តខ្ពស់មានសារៈសំខាន់ជាងទំហំតូច ឬចន្លោះពេលថែទាំយូរ។.

កម្មវិធីល្អបំផុត៖

- ការចែកចាយបីដំណាក់កាល 400V ឬ 690V៖ ខ្នងបង្អែកនៃប្រព័ន្ធអគ្គិសនីឧស្សាហកម្ម និងពាណិជ្ជកម្មភាគច្រើន

- មជ្ឈមណ្ឌលគ្រប់គ្រងម៉ូទ័រ (MCCs)៖ ការការពារសម្រាប់ស្នប់ ម៉ាស៊ីនកង្ហារ ម៉ាស៊ីនបង្ហាប់ ខ្សែក្រវ៉ាត់ និងម៉ូទ័រវ៉ុលទាបផ្សេងទៀត

- មជ្ឈមណ្ឌលគ្រប់គ្រងថាមពល (PCCs)៖ ការចែកចាយសំខាន់សម្រាប់គ្រឿងម៉ាស៊ីនឧស្សាហកម្ម និងឧបករណ៍ដំណើរការ

- បន្ទះចែកចាយមេវ៉ុលទាប (LVMDP)៖ ច្រកចូលសេវាកម្ម និងឧបករណ៍ផ្តាច់មេសម្រាប់អគារ និងបរិក្ខារ

- ការការពារម៉ាស៊ីនភ្លើង៖ ម៉ាស៊ីនភ្លើងបម្រុងវ៉ុលទាប (ជាធម្មតា 480V ឬ 600V)

- សមុទ្រ និងឈូងសមុទ្រ៖ ការចែកចាយថាមពលកប៉ាល់វ៉ុលទាប (ដែល IEC 60092 ក៏អនុវត្តផងដែរ)

ពេលណាដែល ACBs សមហេតុផលផ្នែកហិរញ្ញវត្ថុ៖

- អាទិភាពតម្លៃដំបូងទាបជាង៖ ប្រសិនបើថវិកាដើមទុនមានកម្រិត ហើយអ្នកមានសមត្ថភាពថែទាំផ្ទៃក្នុង

- តម្រូវការចរន្តខ្ពស់៖ នៅពេលដែលអ្នកត្រូវការកម្រិត 6,000A+ ដែលមានសេដ្ឋកិច្ចជាងនៅក្នុងទម្រង់ ACB

- បំពាក់បន្ថែមទៅក្នុង switchgear LV ដែលមានស្រាប់៖ នៅពេលជំនួសដូចគ្នាទៅនឹងបន្ទះដែលបានរចនាសម្រាប់ ACBs

ដែនកំណត់ដែលត្រូវចងចាំ៖

- បន្ទុកថែទាំ៖ រំពឹងថានឹងមានការត្រួតពិនិត្យរៀងរាល់ 6 ខែ និងការជំនួសទំនាក់ទំនងរៀងរាល់ 3-5 ឆ្នាំ

- ទំហំ៖ ACBs មានទំហំធំជាង និងធ្ងន់ជាង VCBs ដែលសមមូលដោយសារតែការផ្គុំ arc chute

- សំលេងរំខាន៖ ការរំខានធ្នូនៅក្នុងខ្យល់គឺខ្លាំងជាងនៅក្នុងកន្លែងបូមធូលីដែលបិទជិត

- អាយុកាលសេវាកម្មមានកំណត់៖ ជាធម្មតា 10,000 ទៅ 15,000 ប្រតិបត្តិការ មុនពេលកែលម្អសំខាន់

ពេលណាត្រូវប្រើ VCBs

Vacuum Circuit Breakers គ្របដណ្តប់ កម្មវិធីវ៉ុលមធ្យម កន្លែងដែលភាពជឿជាក់ ការថែទាំទាប ទំហំតូច និងអាយុកាលសេវាកម្មយូរអង្វែងបង្ហាញអំពីភាពត្រឹមត្រូវនៃតម្លៃដំបូងខ្ពស់ជាង។.

កម្មវិធីល្អបំផុត៖

- ស្ថានីយរងឧបករណ៍ប្រើប្រាស់ 11kV, 22kV, 33kV៖ Switchgear ចែកចាយបឋម និងអនុវិទ្យាល័យ

- Industrial MV switchgear៖ Ring main units (RMUs), metal-clad switchboards, pad-mounted transformers

- ការការពារម៉ូទ័រវ៉ុលខ្ពស់៖ ម៉ូទ័រ Induction ខាងលើ 1,000 HP (ជាធម្មតា 3.3kV, 6.6kV, ឬ 11kV)

- ការការពារ Transformer៖ ឧបករណ៍បំបែកផ្នែកខាងបឋមសម្រាប់ចែកចាយ និងបំលែងថាមពល

- គ្រឿងបរិក្ខារផលិតថាមពល៖ ឧបករណ៍បំបែកសៀគ្វីម៉ាស៊ីនភ្លើង ថាមពលជំនួយស្ថានីយ

- ប្រព័ន្ធថាមពលកកើតឡើងវិញ៖ សៀគ្វីប្រមូលផ្តុំកសិដ្ឋានខ្យល់ ឧបករណ៍បំលែងជំហានឡើងលើពន្លឺព្រះអាទិត្យ

- រ៉ែ និងឧស្សាហកម្មធុនធ្ងន់៖ កន្លែងដែលធូលី សំណើម និងលក្ខខណ្ឌដ៏អាក្រក់ធ្វើឱ្យការថែទាំ ACB មានបញ្ហា

នៅពេលដែល VCBs ជាជម្រើសតែមួយគត់៖

- វ៉ុលប្រព័ន្ធ >1kV AC៖ រូបវិទ្យា និង IEC 62271-100 តម្រូវឱ្យមានឧបករណ៍បំបែកកម្រិតវ៉ុលមធ្យម

- ប្រតិបត្តិការប្តូរញឹកញាប់៖ VCBs ត្រូវបានវាយតម្លៃសម្រាប់ប្រតិបត្តិការមេកានិច 30,000+ (ការរចនាមួយចំនួនលើសពី 100,000 ប្រតិបត្តិការ)

- ការចូលប្រើការថែទាំមានកំណត់៖ ស្ថានីយរងពីចម្ងាយ វេទិកាក្រៅឆ្នេរ ការដំឡើងលើដំបូលដែលការត្រួតពិនិត្យ ACB ប្រចាំឆមាសគឺមិនជាក់ស្តែង

- ការផ្តោតអារម្មណ៍លើតម្លៃវដ្តជីវិតវែង៖ នៅពេលដែលតម្លៃសរុបនៃភាពជាម្ចាស់លើសពី 20-30 ឆ្នាំលើសពីតម្លៃដើមទុនដំបូង

គុណសម្បត្តិនៃបរិស្ថានដ៏អាក្រក់៖

- ឧបករណ៍រំខានខ្វះចន្លោះដែលបិទជិតមិនត្រូវបានប៉ះពាល់ដោយធូលី សំណើម ការបាញ់អំបិល ឬកម្ពស់ (រហូតដល់ដែនកំណត់នៃការបន្ទាប)

- គ្មាន arc chutes ដើម្បីសម្អាត ឬជំនួស

- ប្រតិបត្តិការស្ងាត់ (សំខាន់សម្រាប់ស្ថានីយរងក្នុងផ្ទះនៅក្នុងអគារដែលកាន់កាប់)

- ទំហំតូច (សំខាន់នៅក្នុងស្ថានីយរងក្នុងទីក្រុងដែលមានអចលនទ្រព្យថ្លៃ)

ម៉ាទ្រីសការសម្រេចចិត្ត៖ ACB ឬ VCB?

| លក្ខណៈប្រព័ន្ធរបស់អ្នក | ប្រភេទ Breaker ដែលបានណែនាំ | ហេតុផលចម្បង |

| វ៉ុល ≤ 1,000V AC | ACB | យុត្តាធិការ IEC 60947-2; ការពន្លត់ខ្យល់គឺគ្រប់គ្រាន់ |

| វ៉ុល > 1,000V AC | VCB | IEC 62271-100 តម្រូវ; ខ្យល់មិនអាចរំខានធ្នូបានទេ |

| ចរន្តខ្ពស់ (>5,000A) នៅ LV | ACB | សន្សំសំចៃជាងសម្រាប់ចរន្តខ្ពស់ខ្លាំងនៅវ៉ុលទាប |

| ការប្តូរញឹកញាប់ (>20/ថ្ងៃ) | VCB | វាយតម្លៃសម្រាប់ប្រតិបត្តិការ 30,000+ ទល់នឹង ACB 10,000 |

| បរិស្ថានដ៏អាក្រក់ (ធូលី អំបិល សំណើម) | VCB | ឧបករណ៍រំខានដែលបិទជិតមិនប៉ះពាល់ដោយការចម្លងរោគ |

| ការចូលប្រើការថែទាំមានកំណត់ | VCB | ចន្លោះពេលសេវាកម្ម 3-5 ឆ្នាំ ទល់នឹងកាលវិភាគ 6 ខែរបស់ ACB |

| ការផ្តោតអារម្មណ៍លើតម្លៃវដ្តជីវិត 20+ ឆ្នាំ | VCB | TCO ទាបជាង ទោះបីជាតម្លៃដំបូងខ្ពស់ជាងក៏ដោយ |

| ការរឹតបន្តឹងទំហំតឹង | VCB | ការរចនាតូច; គ្មានបរិមាណ arc chute |

| គម្រោងដើមទុនដែលមានកម្រិតថវិកា | ACB (ប្រសិនបើ ≤1kV) | ចំណាយដំបូងទាប ប៉ុន្តែត្រូវគិតគូរពីថវិកាថែទាំ |

រូបភាពទី 5: គំនូសតាងលំហូរនៃការជ្រើសរើសឧបករណ៍បំលែងសៀគ្វី។ វ៉ុលប្រព័ន្ធគឺជាលក្ខណៈវិនិច្ឆ័យនៃការសម្រេចចិត្តចម្បង ដែលដឹកនាំអ្នកទៅកាន់កម្មវិធី ACB (វ៉ុលទាប) ឬ VCB (វ៉ុលមធ្យម) ដោយផ្អែកលើព្រំដែន 1,000V ។.

គាំទ្រទិព្វ#៤៖ ប្រសិនបើវ៉ុលប្រព័ន្ធរបស់អ្នកនៅជិតព្រំដែន 1kV សូមបញ្ជាក់ VCB ។ កុំព្យាយាមពង្រីក ACB ទៅកម្រិតវ៉ុលអតិបរមារបស់វា។ ពិដានវ៉ុល មិនមែនជា “អតិបរមាដែលបានវាយតម្លៃ” ទេ — វាជាដែនកំណត់រូបវិទ្យាដ៏តឹងរឹង។ រចនាដោយមានរឹម។.

ពន្ធថែទាំ៖ ហេតុអ្វីបានជា VCB ចំណាយតិចជាងក្នុងរយៈពេល 20 ឆ្នាំ

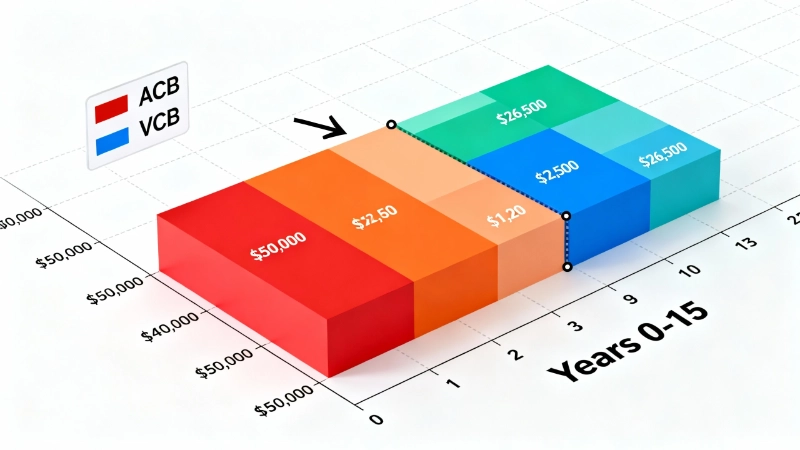

ACB $15,000 មើលទៅគួរឱ្យទាក់ទាញបើប្រៀបធៀបទៅនឹង VCB $25,000 ។ រហូតដល់អ្នកដំណើរការលេខលើសពី 15 ឆ្នាំ។.

សូមស្វាគមន៍មកកាន់ ពន្ធថែទាំ—ការចំណាយកើតឡើងដដែលៗដែលលាក់កំបាំង ដែលផ្លាស់ប្តូរសមីការសេដ្ឋកិច្ច។.

ការថែទាំ ACB៖ បន្ទុកពីរដងក្នុងមួយឆ្នាំ

ឧបករណ៍បំលែងសៀគ្វីខ្យល់ទាមទារការថែទាំដោយដៃជាប្រចាំ ពីព្រោះទំនាក់ទំនង និងរន្ធធ្នូរបស់វាដំណើរការនៅក្នុងបរិយាកាសខ្យល់បើកចំហ។ នេះគឺជាកាលវិភាគថែទាំធម្មតាដែលបានណែនាំដោយក្រុមហ៊ុនផលិត និង IEC 60947-2៖

រៀងរាល់ 6 ខែម្តង (ការត្រួតពិនិត្យពាក់កណ្តាលប្រចាំឆ្នាំ)៖

- ការត្រួតពិនិត្យមើលឃើញនៃទំនាក់ទំនងសម្រាប់ការរណ្តៅ ការច្រេះ ឬការប្រែពណ៌

- ការសម្អាតរន្ធធ្នូ (ការដកប្រាក់បញ្ញើកាបូន និងសំណល់ចំហាយលោហៈ)

- ការវាស់ចន្លោះទំនាក់ទំនង និងការជូត

- ការធ្វើតេស្តប្រតិបត្តិការមេកានិច (ដោយដៃ និងស្វ័យប្រវត្តិ)

- ការត្រួតពិនិត្យកម្លាំងបង្វិលជុំនៃការតភ្ជាប់ស្ថានីយ

- ការរំអិលផ្នែកដែលផ្លាស់ទី (ហ៊ីង តំណភ្ជាប់ សត្វខ្លាឃ្មុំ)

- ការធ្វើតេស្តមុខងារនៃអង្គភាពធ្វើដំណើរលើសចរន្ត

រៀងរាល់ 3-5 ឆ្នាំម្តង (សេវាកម្មធំ)៖

- ការជំនួសទំនាក់ទំនង (ប្រសិនបើការច្រេះលើសពីដែនកំណត់របស់អ្នកផលិត)

- ការត្រួតពិនិត្យរន្ធធ្នូ និងការជំនួសប្រសិនបើខូច

- ការធ្វើតេស្តភាពធន់នឹងអ៊ីសូឡង់ (ការធ្វើតេស្តមេហ្គាហ្គ័រ)

- ការវាស់វែងធន់នឹងទំនាក់ទំនង

- ការរុះរើ និងសម្អាតពេញលេញ

- ការជំនួសសមាសធាតុមេកានិចដែលពាក់

ការបំបែកការចំណាយ (ធម្មតា ប្រែប្រួលតាមតំបន់)៖

- ការត្រួតពិនិត្យពាក់កណ្តាលប្រចាំឆ្នាំ៖ $600-$1,000 ក្នុងមួយឧបករណ៍បំលែង (កម្លាំងពលកម្មរបស់អ្នកម៉ៅការ៖ 3-4 ម៉ោង)

- ការជំនួសទំនាក់ទំនង៖ $2,500-$4,000 (គ្រឿងបន្លាស់ + កម្លាំងពលកម្ម)

- ការជំនួសរន្ធធ្នូ៖ $1,500-$2,500 (ប្រសិនបើខូច)

- ការហៅសេវាសង្គ្រោះបន្ទាន់ (ប្រសិនបើឧបករណ៍បំលែងបរាជ័យរវាងការត្រួតពិនិត្យ)៖ $1,500-$3,000

សម្រាប់ ACB ដែលមានអាយុកាលសេវាកម្ម 15 ឆ្នាំ៖

- ការត្រួតពិនិត្យពាក់កណ្តាលប្រចាំឆ្នាំ៖ 15 ឆ្នាំ × 2 ការត្រួតពិនិត្យ/ឆ្នាំ × $800 ជាមធ្យម = $24,000

- ការជំនួសទំនាក់ទំនង៖ (15 ឆ្នាំ ÷ 4 ឆ្នាំ) × $3,000 = $9,000 (3 ការជំនួស)

- ការបរាជ័យដែលមិនបានគ្រោងទុក៖ សន្មតថាមានការបរាជ័យ 1 × $2,000 = $2,000

- ការថែទាំសរុបលើសពី 15 ឆ្នាំ៖ $35,000

បន្ថែមការចំណាយលើការទិញដំបូង ($15,000) និងរបស់អ្នក ការចំណាយសរុបនៃភាពជាម្ចាស់រយៈពេល 15 ឆ្នាំគឺ ~$50,000.

នោះហើយជា ពន្ធថែទាំ. ។ អ្នកបង់វាក្នុងម៉ោងធ្វើការ ការឈប់សម្រាក និងគ្រឿងបន្លាស់ប្រើប្រាស់ — រៀងរាល់ឆ្នាំ ពីរដងក្នុងមួយឆ្នាំ សម្រាប់អាយុកាលរបស់ឧបករណ៍បំលែង។.

ការថែទាំ VCB៖ គុណសម្បត្តិនៃការផ្សាភ្ជាប់សម្រាប់អាយុកាល

ឧបករណ៍បំលែងសៀគ្វីខ្វះចន្លោះ ផ្លាស់ប្តូរសមីការថែទាំ។ ឧបករណ៍រំខានខ្វះចន្លោះដែលបានផ្សាភ្ជាប់ការពារទំនាក់ទំនងពីការកត់សុី ការចម្លងរោគ និងការប៉ះពាល់បរិស្ថាន។ លទ្ធផល៖ ចន្លោះពេលសេវាកម្មបានពង្រីកយ៉ាងខ្លាំង។.

រៀងរាល់ 3-5 ឆ្នាំម្តង (ការត្រួតពិនិត្យតាមកាលកំណត់)៖

- ការត្រួតពិនិត្យខាងក្រៅដោយមើលឃើញ

- ការត្រួតពិនិត្យចំនួនប្រតិបត្តិការមេកានិច (តាមរយៈបញ្ជរ ឬចំណុចប្រទាក់ឌីជីថល)

- ការត្រួតពិនិត្យសូចនាករសំណឹកទំនាក់ទំនង (VCB ខ្លះមានសូចនាករខាងក្រៅ)

- ការធ្វើតេស្តប្រតិបត្តិការ (វដ្តបើក/បិទ)

- ការធ្វើតេស្តមុខងារសៀគ្វីត្រួតពិនិត្យ

- ការត្រួតពិនិត្យការតភ្ជាប់ស្ថានីយ

រៀងរាល់ 10-15 ឆ្នាំម្តង (ការត្រួតពិនិត្យធំ ប្រសិនបើមាន)៖

- ការធ្វើតេស្តសុចរិតភាពខ្វះចន្លោះ (ដោយប្រើការធ្វើតេស្តវ៉ុលខ្ពស់ ឬការត្រួតពិនិត្យកាំរស្មីអ៊ិច)

- ការវាស់ចន្លោះទំនាក់ទំនង (តម្រូវឱ្យមានការរុះរើដោយផ្នែកលើម៉ូដែលមួយចំនួន)

- ការធ្វើតេស្តភាពធន់នឹងអ៊ីសូឡង់

កត់សម្គាល់អ្វីដែល មិន នៅក្នុងបញ្ជី៖

- គ្មានការសម្អាតទំនាក់ទំនង (បរិយាកាសបិទជិត)

- គ្មានការថែទាំរន្ធធ្នូ (មិនមាន)

- គ្មានការត្រួតពិនិត្យពាក់កណ្តាលប្រចាំឆ្នាំ (មិនចាំបាច់)

- គ្មានការជំនួសទំនាក់ទំនងជាប្រចាំ (អាយុកាល 20-30 ឆ្នាំ)

ការបំបែកការចំណាយ (ធម្មតា)៖

- ការត្រួតពិនិត្យតាមកាលកំណត់ (រៀងរាល់ 4 ឆ្នាំម្តង)៖ $400-$700 ក្នុងមួយឧបករណ៍បំលែង (កម្លាំងពលកម្មរបស់អ្នកម៉ៅការ៖ 1.5-2 ម៉ោង)

- ការជំនួសឧបករណ៍រំខានខ្វះចន្លោះ (បើចាំបាច់បន្ទាប់ពី 20-25 ឆ្នាំ)៖ $6,000-$10,000

សម្រាប់ VCB ដែលមានរយៈពេលវាយតម្លៃដូចគ្នា 15 ឆ្នាំ៖

- ការត្រួតពិនិត្យតាមកាលកំណត់៖ (15 ឆ្នាំ ÷ 4 ឆ្នាំ) × $500 ជាមធ្យម = $1,500 (3 ការត្រួតពិនិត្យ)

- ការបរាជ័យដែលមិនបានគ្រោងទុក៖ កម្រណាស់។ សន្មតថា 0% (VCB មានអត្រាបរាជ័យទាបជាង 10 ដង)

- ការកែលម្អធំៗ៖ មិនចាំបាច់ក្នុងរយៈពេល 15 ឆ្នាំទេ។

- ការថែទាំសរុបក្នុងរយៈពេល 15 ឆ្នាំ៖ $1,500

បន្ថែមថ្លៃដើមនៃការទិញដំបូង ($25,000) ហើយ ថ្លៃដើមសរុបនៃការកាន់កាប់រយៈពេល 15 ឆ្នាំរបស់អ្នកគឺប្រហែល $26,500.

ចំណុចប្រសព្វ TCO

សូមដាក់វានៅទន្ទឹមគ្នា៖

| ធាតុផ្សំនៃថ្លៃដើម | ACB (15 ឆ្នាំ) | VCB (15 ឆ្នាំ) |

| ការទិញដំបូង | $15,000 | $25,000 |

| ការថែទាំតាមទម្លាប់ | $24,000 | $1,500 |

| ការជំនួសទំនាក់ទំនង/សមាសធាតុ | $9,000 | $0 |

| ការបរាជ័យដែលមិនបានគ្រោងទុក | $2,000 | $0 |

| ការចំណាយសរុបនៃកម្មសិទ្ធិ | $50,000 | $26,500 |

| ថ្លៃដើមក្នុងមួយឆ្នាំ | $3,333/ឆ្នាំ | $1,767/ឆ្នាំ |

VCB សងថ្លៃខ្លួនឯង តាមរយៈការសន្សំសំចៃលើការថែទាំតែប៉ុណ្ណោះ។ ប៉ុន្តែនេះគឺជាចំណុចសំខាន់៖ ចំណុចប្រសព្វកើតឡើងនៅជុំវិញឆ្នាំទី 3.

- ឆ្នាំទី 0៖ ACB = $15K, VCB = $25K (ACB នាំមុខដោយ $10K)

- ឆ្នាំទី 1.5៖ ការត្រួតពិនិត្យ ACB 3 លើកដំបូង = $2,400; VCB = $0 (ACB នាំមុខដោយ $7,600)

- ឆ្នាំទី 3៖ ការត្រួតពិនិត្យ ACB 6 លើក = $4,800; VCB = $0 (ACB នាំមុខដោយ $5,200)

- ឆ្នាំទី 4៖ ការជំនួសទំនាក់ទំនង ACB លើកដំបូង + ការត្រួតពិនិត្យ 8 លើក = $9,400; ការត្រួតពិនិត្យ VCB លើកដំបូង = $500 (ACB នាំមុខដោយ $900)

- ឆ្នាំទី 5៖ ការថែទាំសរុបរបស់ ACB = $12,000; VCB = $500 (VCB ចាប់ផ្តើមសន្សំប្រាក់)

- ឆ្នាំទី 15៖ ACB សរុប = $50K; VCB សរុប = $26.5K (VCB សន្សំបាន $23,500)

រូបភាពទី 4៖ ការវិភាគថ្លៃដើមសរុបនៃការកាន់កាប់ (TCO) រយៈពេល 15 ឆ្នាំ។ ទោះបីជាថ្លៃដើមដំបូងខ្ពស់ជាងក៏ដោយ VCB កាន់តែសន្សំសំចៃជាង ACB នៅឆ្នាំទី 3 ដោយសារតែតម្រូវការថែទាំទាបជាងយ៉ាងខ្លាំង ដោយសន្សំបាន $23,500 ក្នុងរយៈពេល 15 ឆ្នាំ។.

ប្រសិនបើអ្នកមានគម្រោងរក្សាប្តូរប្តូររយៈពេល 20 ឆ្នាំ (ជាទូទៅសម្រាប់រោងចក្រឧស្សាហកម្ម) គម្លាតនៃការសន្សំកាន់តែធំឡើងដល់ $35,000+ ក្នុងមួយឧបករណ៍បំលែង. ។ សម្រាប់ស្ថានីយប្តូរដែលមានឧបករណ៍បំលែង 10 នោះគឺ $350,000 ក្នុងការសន្សំសំចៃពេញមួយជីវិត.

ថ្លៃដើមលាក់កំបាំងលើសពីវិក្កយបត្រ

ការគណនា TCO ខាងលើគ្រាន់តែចាប់យកថ្លៃដើមផ្ទាល់ប៉ុណ្ណោះ។ កុំភ្លេច៖

ហានិភ័យនៃការផ្អាកដំណើរការ៖

- ការបរាជ័យ ACB រវាងការត្រួតពិនិត្យអាចបណ្តាលឱ្យមានការដាច់ចរន្តដែលមិនបានគ្រោងទុក

- ការបរាជ័យ VCB កម្រណាស់ (MTBF ជារឿយៗលើសពី 30 ឆ្នាំជាមួយនឹងការប្រើប្រាស់ត្រឹមត្រូវ)

ភាពអាចរកបាននៃកម្លាំងពលកម្ម៖

- ការស្វែងរកអ្នកបច្ចេកទេសដែលមានសមត្ថភាពសម្រាប់ការថែទាំ ACB កាន់តែពិបាកនៅពេលដែលឧស្សាហកម្មផ្លាស់ប្តូរទៅ VCB

- រយៈពេលថែទាំពាក់កណ្តាលប្រចាំឆ្នាំតម្រូវឱ្យមានការផ្អាកដំណើរការផលិត ឬការកំណត់ពេលដោយប្រុងប្រយ័ត្ន

សុវត្ថិភាព៖

- ឧប្បត្តិហេតុឆាបឆេះអគ្គិសនី ACB កំឡុងពេលថែទាំគឺជារឿងធម្មតាជាងឧប្បត្តិហេតុ VCB (ទំនាក់ទំនងបើកចំហធៀបនឹងឧបករណ៍រំខានដែលបានផ្សាភ្ជាប់)

- តម្រូវការ PPE ឆាបឆេះអគ្គិសនីកាន់តែតឹងរ៉ឹងសម្រាប់ការថែទាំ ACB

កត្តាបរិស្ថាន៖

- ACBs នៅក្នុងបរិយាកាសដែលមានធូលី សំណើម ឬច្រេះត្រូវការ ច្រើនជាង ការថែទាំញឹកញាប់ (ប្រចាំត្រីមាសជំនួសឱ្យពាក់កណ្តាលប្រចាំឆ្នាំ)

- VCB មិនរងផលប៉ះពាល់ទេ — ឧបករណ៍រំខានដែលបានផ្សាភ្ជាប់មិនខ្វល់ពីលក្ខខណ្ឌខាងក្រៅទេ។

គន្លឹះជំនាញ #5 (ចំណុចធំ)៖ គណនាថ្លៃដើមសរុបនៃការកាន់កាប់លើអាយុកាលរំពឹងទុកនៃការប្តូរប្តូរ (15-25 ឆ្នាំ) មិនត្រឹមតែថ្លៃដើមដើមប៉ុណ្ណោះទេ។ សម្រាប់កម្មវិធីវ៉ុលមធ្យម VCB ស្ទើរតែតែងតែឈ្នះលើ TCO ។ សម្រាប់កម្មវិធីវ៉ុលទាបដែលអ្នកត្រូវតែប្រើ ACB សូមកំណត់ថវិកា $2,000-$3,000 ក្នុងមួយឆ្នាំក្នុងមួយឧបករណ៍បំលែងសម្រាប់ការថែទាំ — ហើយកុំឱ្យកាលវិភាគថែទាំរអិល។ ការរំលងការត្រួតពិនិត្យប្រែទៅជាការបរាជ័យដ៏មហន្តរាយ។.

សំណួរដែលគេសួរញឹកញាប់៖ ACB vs VCB

សំណួរ៖ តើខ្ញុំអាចប្រើ ACB លើសពី 1,000V បានទេ ប្រសិនបើខ្ញុំបន្ថយវា ឬបន្ថែមការទប់ស្កាត់ធ្នូខាងក្រៅ?

ចម្លើយ៖ ទេ។ ដែនកំណត់ 1,000V សម្រាប់ ACBs មិនមែនជាបញ្ហាកំដៅ ឬភាពតានតឹងអគ្គិសនីដែលការបន្ថយអាចដោះស្រាយបាននោះទេ — វាជាដែនកំណត់រូបវិទ្យាធ្នូមូលដ្ឋាន។ លើសពី 1kV ខ្យល់បរិយាកាសមិនអាចពន្លត់ធ្នូបានយ៉ាងគួរឱ្យទុកចិត្តក្នុងរយៈពេលសុវត្ថិភាពទេ ទោះបីជាអ្នកកំណត់រចនាសម្ព័ន្ធឧបករណ៍បំលែងយ៉ាងណាក៏ដោយ។ IEC 60947-2 កំណត់យ៉ាងច្បាស់នូវ ACBs ទៅ ≤1,000V AC ហើយការដំណើរការនៅខាងក្រៅវិសាលភាពនោះរំលោភលើស្តង់ដារ និងបង្កើតគ្រោះថ្នាក់ឆាបឆេះអគ្គិសនី។ ប្រសិនបើប្រព័ន្ធរបស់អ្នកលើសពី 1kV អ្នកត្រូវតែប្រើឧបករណ៍បំលែងវ៉ុលមធ្យម (VCB ឬឧបករណ៍បំលែង SF6 យោងតាម IEC 62271-100) ដោយស្របច្បាប់ និងសុវត្ថិភាព។.

សំណួរ៖ តើ VCB មានតម្លៃថ្លៃជាងក្នុងការជួសជុលជាង ACB ដែរឬទេ ប្រសិនបើមានអ្វីខុស?

ចម្លើយ៖ បាទ ប៉ុន្តែ VCB បរាជ័យតិចជាញឹកញាប់។ នៅពេលដែលឧបករណ៍រំខានខ្វះចន្លោះ VCB បរាជ័យ (កម្រ) ជាធម្មតាវាទាមទារឱ្យមានការជំនួសរោងចក្រនៃអង្គភាពដែលបានផ្សាភ្ជាប់ទាំងមូលក្នុងតម្លៃ $6,000-$10,000 ។ ទំនាក់ទំនង ACB និងជណ្តើរយន្តធ្នូអាចត្រូវបានផ្តល់សេវាកម្មនៅក្នុងវាលក្នុងតម្លៃ $2,500-$4,000 ប៉ុន្តែអ្នកនឹងជំនួសវាក្នុងរយៈពេល 3-4 ដងនៃអាយុកាលរបស់ VCB ។ គណិតវិទ្យានៅតែពេញចិត្ត VCB៖ ការជំនួសឧបករណ៍រំខាន VCB មួយក្នុងរយៈពេល 25 ឆ្នាំ ធៀបនឹងការជំនួសទំនាក់ទំនង ACB បីក្នុងរយៈពេល 15 ឆ្នាំ បូកនឹងការបន្ត ពន្ធថែទាំ រៀងរាល់ប្រាំមួយខែម្តង។.

សំណួរ៖ តើប្រភេទឧបករណ៍បំលែងមួយណាដែលល្អជាងសម្រាប់ការប្តូរញឹកញាប់ (ធនាគារ capacitor ការចាប់ផ្តើមម៉ូទ័រ)?

ចម្លើយ៖ VCB ដោយរឹមធំទូលាយ។ ឧបករណ៍បំលែងសៀគ្វីខ្វះចន្លោះត្រូវបានវាយតម្លៃសម្រាប់ប្រតិបត្តិការមេកានិចពី 30,000 ទៅ 100,000+ មុនពេលកែលម្អធំៗ។ ACBs ជាធម្មតាត្រូវបានវាយតម្លៃសម្រាប់ប្រតិបត្តិការពី 10,000 ទៅ 15,000 ។ សម្រាប់កម្មវិធីដែលពាក់ព័ន្ធនឹងការប្តូរញឹកញាប់ — ដូចជាការប្តូរធនាគារ capacitor ការចាប់ផ្តើម/បញ្ឈប់ម៉ូទ័រនៅក្នុងដំណើរការបាច់ ឬគ្រោងការណ៍ផ្ទេរការផ្ទុក — VCB នឹងលើស ACB ដោយ 3:1 ទៅ 10:1 ក្នុងការរាប់ប្រតិបត្តិការ។ លើសពីនេះទៀត ការពន្លត់ធ្នូយ៉ាងលឿនរបស់ VCB (វដ្តមួយ) កាត់បន្ថយភាពតានតឹងលើឧបករណ៍ខាងក្រោមក្នុងអំឡុងពេលព្រឹត្តិការណ៍ប្តូរនីមួយៗ។.

សំណួរ៖ តើ VCB មានគុណវិបត្តិណាមួយបើប្រៀបធៀបទៅនឹង ACB លើសពីថ្លៃដើមដំបូងដែរឬទេ?

ចម្លើយ៖ ការពិចារណាតិចតួចចំនួនបី៖ (1) ហានិភ័យនៃវ៉ុលលើស នៅពេលប្ដូរបន្ទុក capacitive ឬ inductive—ការរលត់ធ្នូភ្លើងយ៉ាងរហ័សរបស់ VCB អាចបង្កើតវ៉ុលលើសបណ្ដោះអាសន្នដែលអាចតម្រូវឱ្យមានឧបករណ៍ទប់លំនឹង ឬ RC snubbers សម្រាប់បន្ទុកដែលងាយរងគ្រោះ។ (2) ភាពស្មុគស្មាញនៃការជួសជុល—ប្រសិនបើឧបករណ៍កាត់ខ្វះចន្លោះបរាជ័យ អ្នកមិនអាចជួសជុលវានៅនឹងកន្លែងបានទេ។ ឯកតាទាំងមូលត្រូវតែត្រូវបានជំនួស។ (3) សំឡេងរអ៊ូរទាំដែលអាចឮបាន—ការរចនា VCB មួយចំនួនបង្កើតសំឡេងរអ៊ូរទាំប្រេកង់ទាបពីយន្តការប្រតិបត្តិការ ទោះបីជាសំឡេងនេះស្ងាត់ជាងការផ្ទុះធ្នូភ្លើងរបស់ ACB ក៏ដោយ។ សម្រាប់ 99% នៃការប្រើប្រាស់ គុណវិបត្តិទាំងនេះគឺមិនសំខាន់បើប្រៀបធៀបទៅនឹងគុណសម្បត្តិ (សូមមើល គុណសម្បត្តិនៃការផ្សាភ្ជាប់សម្រាប់អាយុកាល ផ្នែក)។.

សំណួរ៖ តើខ្ញុំអាចបំពាក់ VCB ទៅក្នុងបន្ទះឧបករណ៍ប្ដូរប្ដូរ ACB ដែលមានស្រាប់បានទេ?

ចម្លើយ៖ ពេលខ្លះអាចធ្វើបាន ប៉ុន្តែមិនតែងតែទេ។ VCB មានទំហំតូចជាង ACB ដូច្នេះទំហំរូបវន្តកម្រជាបញ្ហាណាស់។ បញ្ហាប្រឈមគឺ៖ (1) វិមាត្រម៉ោន—លំនាំរន្ធម៉ោន ACB និង VCB ខុសគ្នា។ អ្នកប្រហែលជាត្រូវការបន្ទះអាដាប់ទ័រ។ (2) Busbar ការកំណត់រចនាសម្ព័ន្ធ—ស្ថានីយ VCB ប្រហែលជាមិនស៊ីគ្នានឹង busbars ACB ដែលមានស្រាប់ដោយគ្មានការកែប្រែទេ។ (3) វ៉ុលបញ្ជា—យន្តការប្រតិបត្តិការ VCB អាចត្រូវការថាមពលបញ្ជាខុសគ្នា (ឧទាហរណ៍ 110V DC ទល់នឹង 220V AC)។ (4) សម្របសម្រួលការការពារ—ការផ្លាស់ប្ដូរប្រភេទឧបករណ៍បំបែកសៀគ្វីអាចផ្លាស់ប្ដូរពេលវេលានៃការសម្អាតសៀគ្វីខ្លី និងខ្សែកោងសម្របសម្រួល។ តែងតែពិគ្រោះជាមួយក្រុមហ៊ុនផលិតឧបករណ៍ប្ដូរប្ដូរ ឬវិស្វករអគ្គិសនីដែលមានលក្ខណៈសម្បត្តិគ្រប់គ្រាន់ មុនពេលបំពាក់ឡើងវិញ។ ការដំឡើងថ្មីគួរតែបញ្ជាក់ VCB សម្រាប់វ៉ុលមធ្យម និង ACB (ឬ MCCBs) សម្រាប់វ៉ុលទាបតាំងពីដំបូង។.

សំណួរ៖ ហេតុអ្វីបានជាក្រុមហ៊ុនផលិតមិនផលិត ACB សម្រាប់វ៉ុលមធ្យម (11kV, 33kV)?

ចម្លើយ៖ ពួកគេបានព្យាយាម។ ACB វ៉ុលមធ្យមមាននៅក្នុងពាក់កណ្ដាលសតវត្សទី 20 ប៉ុន្តែពួកវាមានទំហំធំសម្បើម—ឧបករណ៍បំបែកសៀគ្វីទំហំបន្ទប់ដែលមាន arc chutes ប្រវែងជាច្រើនម៉ែត្រ។ កម្លាំង dielectric ទាបនៃខ្យល់ (~3 kV/mm) មានន័យថាឧបករណ៍បំបែកសៀគ្វី 33kV ត្រូវការគម្លាតទំនាក់ទំនង និង arc chutes ដែលវាស់វែងជាម៉ែត្រ មិនមែនមីលីម៉ែត្រទេ។ ទំហំ ទម្ងន់ បន្ទុកថែទាំ និងហានិភ័យនៃការឆេះបានធ្វើឱ្យពួកវាមិនជាក់ស្តែង។ នៅពេលដែលបច្ចេកវិទ្យាឧបករណ៍កាត់ខ្វះចន្លោះបានពេញវ័យនៅទសវត្សរ៍ឆ្នាំ 1960-1970 ACB វ៉ុលមធ្យមត្រូវបានលែងប្រើ។ សព្វថ្ងៃនេះ ឧបករណ៍បំបែកខ្វះចន្លោះ និង SF6 គ្របដណ្ដប់លើទីផ្សារវ៉ុលមធ្យម ពីព្រោះរូបវិទ្យា និងសេដ្ឋកិច្ចទាំងពីរពេញចិត្តការរចនាឧបករណ៍កាត់ដែលបានផ្សាភ្ជាប់ខាងលើ 1kV។ នោះ ពិដានវ៉ុល មិនមែនជាការសម្រេចចិត្តផលិតផលទេ—វាជាការពិតផ្នែកវិស្វកម្ម។.

សេចក្តីសន្និដ្ឋាន៖ វ៉ុលជាមុន បន្ទាប់មកអ្វីៗផ្សេងទៀតដើរតាម

ចងចាំសន្លឹកទិន្នន័យទាំងពីរពីការបើក? ទាំងពីរបានរាយបញ្ជីការវាយតម្លៃវ៉ុលរហូតដល់ 690V។ ទាំងពីរបានអះអាងពីសមត្ថភាពបំបែកដ៏រឹងមាំ។ ប៉ុន្តែឥឡូវនេះអ្នកដឹងហើយ៖ វ៉ុលមិនមែនគ្រាន់តែជាលេខទេ—វាជាបន្ទាត់បែងចែករវាងបច្ចេកវិទ្យាឧបករណ៍បំបែកសៀគ្វី។.

នេះគឺជាក្របខ័ណ្ឌនៃការសម្រេចចិត្តជាបីផ្នែក៖

1. វ៉ុលកំណត់ប្រភេទឧបករណ៍បំបែកសៀគ្វី (ដែនកំណត់វ៉ុល)

- វ៉ុលប្រព័ន្ធ ≤1,000V AC → ឧបករណ៍បំបែកសៀគ្វីខ្យល់ (ACB) គ្រប់គ្រងដោយ IEC 60947-2:2024

- វ៉ុលប្រព័ន្ធ >1,000V AC → ឧបករណ៍បំបែកសៀគ្វីខ្វះចន្លោះ (VCB) គ្រប់គ្រងដោយ IEC 62271-100:2021+A1:2024

- នេះមិនអាចចរចាបានទេ។ រូបវិទ្យាកំណត់ព្រំដែន; ស្តង់ដារបានធ្វើឱ្យវាជាផ្លូវការ។.

2. ស្តង់ដារធ្វើឱ្យការបំបែកជាផ្លូវការ (ការបំបែកស្តង់ដារ)

- IEC មិនបានបង្កើតស្តង់ដារដាច់ដោយឡែកពីរសម្រាប់ការបែងចែកទីផ្សារទេ—ពួកគេបានសរសេរកូដការពិតដែលថាការរំខានធ្នូភ្លើងដោយផ្អែកលើខ្យល់បរាជ័យខាងលើ 1kV

- វ៉ុលប្រព័ន្ធរបស់អ្នកប្រាប់អ្នកថាស្តង់ដារណាមួយអនុវត្ត ដែលប្រាប់អ្នកថាបច្ចេកវិទ្យាឧបករណ៍បំបែកសៀគ្វីមួយណាដែលត្រូវបញ្ជាក់

- ពិនិត្យមើលសញ្ញាសម្គាល់ការអនុលោមតាម IEC របស់ឧបករណ៍បំបែកសៀគ្វី៖ 60947-2 = វ៉ុលទាប, 62271-100 = វ៉ុលមធ្យម

3. ការថែទាំកំណត់សេដ្ឋកិច្ចនៃអាយុកាល (ពន្ធថែទាំ)

- ACB ចំណាយតិចនៅពេលខាងមុខ ប៉ុន្តែត្រូវចំណាយ $2,000-$3,000/ឆ្នាំ ក្នុងការត្រួតពិនិត្យពាក់កណ្ដាលឆ្នាំ និងការជំនួសទំនាក់ទំនង

- VCB ចំណាយច្រើនជាងដំបូង ប៉ុន្តែត្រូវការការត្រួតពិនិត្យតែរៀងរាល់ 3-5 ឆ្នាំម្ដង ជាមួយនឹងអាយុកាលទំនាក់ទំនង 20-30 ឆ្នាំ

- ការផ្លាស់ប្ដូរ TCO កើតឡើងនៅជុំវិញឆ្នាំទី 3; គិតត្រឹមឆ្នាំទី 15 VCB សន្សំបាន $20,000-$25,000 ក្នុងមួយឧបករណ៍បំបែកសៀគ្វី

- សម្រាប់កម្មវិធីវ៉ុលមធ្យម (ដែលអ្នកត្រូវតែប្រើ VCB យ៉ាងណាក៏ដោយ) គុណសម្បត្តិនៃការចំណាយគឺជាប្រាក់រង្វាន់

- សម្រាប់កម្មវិធីវ៉ុលទាប (ដែល ACB សមស្រប) សូមធ្វើផែនការថវិកាសម្រាប់ពន្ធថែទាំ ពន្ធថែទាំ ហើយប្រកាន់ខ្ជាប់នូវកាលវិភាគត្រួតពិនិត្យ

សន្លឹកទិន្នន័យអាចបង្ហាញការវាយតម្លៃវ៉ុលត្រួតគ្នា។ ខិត្តប័ណ្ណទីផ្សារអាចបង្កប់ន័យថាពួកវាអាចផ្លាស់ប្ដូរគ្នាបាន។ ប៉ុន្តែរូបវិទ្យាមិនចរចាទេ ហើយអ្នកក៏មិនគួរដែរ។.

ជ្រើសរើសដោយផ្អែកលើវ៉ុលប្រព័ន្ធរបស់អ្នក។. អ្វីៗផ្សេងទៀត—ការវាយតម្លៃបច្ចុប្បន្ន សមត្ថភាពបំបែក ចន្លោះពេលថែទាំ ទំហំ—ធ្លាក់ចូលកន្លែងនៅពេលដែលអ្នកបានធ្វើការជ្រើសរើសដំបូងនោះបានត្រឹមត្រូវ។.

ត្រូវការជំនួយក្នុងការជ្រើសរើសឧបករណ៍បំបែកសៀគ្វីត្រឹមត្រូវ?

ក្រុមវិស្វកម្មកម្មវិធីរបស់ VIOX មានបទពិសោធន៍រាប់ទសវត្សរ៍ក្នុងការបញ្ជាក់ ACB និង VCB សម្រាប់កម្មវិធីឧស្សាហកម្ម ពាណិជ្ជកម្ម និងឧបករណ៍ប្រើប្រាស់ទូទាំងពិភពលោក។ មិនថាអ្នកកំពុងរចនា MCC 400V ថ្មី កំពុងធ្វើឱ្យប្រសើរឡើងនូវស្ថានីយរង 11kV ឬដោះស្រាយបញ្ហាការបរាជ័យឧបករណ៍បំបែកសៀគ្វីញឹកញាប់នោះទេ យើងនឹងពិនិត្យមើលតម្រូវការប្រព័ន្ធរបស់អ្នក និងណែនាំដំណោះស្រាយដែលអនុលោមតាម IEC ដែលមានតុល្យភាពនៃដំណើរការ សុវត្ថិភាព និងការចំណាយលើអាយុកាល។.

ទាក់ទង VIOX ថ្ងៃនេះសម្រាប់៖ today សម្រាប់៖

- ការជ្រើសរើសឧបករណ៍បំបែកសៀគ្វី និងការគណនាទំហំ

- ការសិក្សាសម្របសម្រួលសៀគ្វីខ្លី

- ការវាយតម្លៃលទ្ធភាពនៃការបំពាក់ឧបករណ៍ប្ដូរប្ដូរឡើងវិញ

- ការបង្កើនប្រសិទ្ធភាពការថែទាំ និងការវិភាគ TCO

ពីព្រោះការទទួលបានប្រភេទឧបករណ៍បំបែកសៀគ្វីខុស មិនត្រឹមតែមានតម្លៃថ្លៃប៉ុណ្ណោះទេ—វាមានគ្រោះថ្នាក់។.