أنت تحدد مواصفات القاطع الرئيسي الوارد لمنشأة تصنيع جديدة بقدرة 2 ميجاوات. الميزانية تقول قاطع MCCB - يوفر 7000 دولار أمريكي مقارنة بقاطع ICCB. حدسك يقول أن هناك شيئًا خاطئًا، لكنك لا تستطيع تحديده تمامًا. أنت توافق على قاطع MCCB.

بعد ستة أشهر: 2:47 صباحًا. اتصال مفكوك في اللوحة 3B يتسبب في حدوث قوس كهربائي.

في غضون 83 مللي ثانية، تنقطع الكهرباء عن المنشأة بأكملها.

ليس فقط اللوحة 3B. ليس فقط التوزيع الفرعي الذي يغذيها. الرئيسية قاطع MCCB يفصل، مما يؤدي إلى قطع الطاقة عن كل آلة، وكل جهاز كمبيوتر، وكل وحدة تحكم في العمليات في المبنى. بحلول الوقت الذي يصل فيه فريق الصيانة في الساعة 4:15 صباحًا، يكون الإنتاج قد توقف لمدة 90 دقيقة. بحلول شروق الشمس، أنت تنظر إلى خسائر في الإنتاج بقيمة 124000 دولار أمريكي، بالإضافة إلى العمل الإضافي الطارئ، والمواد قيد التصنيع المهملة.

السبب الجذري؟ قاطع MCCB الخاص بك بقيمة 1200 دولار أمريكي فعل بالضبط ما صُمم لفعله - الفصل الفوري عند تيار العطل العالي. كانت هذه هي المشكلة.

لم يكن لديه تصنيف Icw- لا توجد قدرة على “الانتظار والمراقبة” بينما يقوم القاطع الموجود في اتجاه المصب بإزالة العطل أولاً. مرحبا بكم في قاتل التتالي مشكلة. أو بالأحرى، عدم وجود واحدة.

الفرق الحقيقي بين MCCB و ICCB (ليس قدرة الفصل)

إذا سألت معظم المهندسين عن قاطع MCCB مقابل قاطع ICCB، فسيخبرونك عن قدرة الفصل - تصنيف Icu. “قواطع MCCB تصل إلى قدرة فصل 150 كيلو أمبير، وقواطع ICCB تصل إلى أعلى من ذلك.” هذا صحيح بما فيه الكفاية. لكن هذه هي المواصفات الخاطئة التي يجب أن تهتم بها.

العامل المميز الحقيقي؟ تيار التحمل لفترة قصيرة (Icw).

إليك ما يعنيه ذلك.

أن MCCB (قاطع الدائرة ذو العلبة المقولبة) عادةً ما يكون لديه قدرة فصل نهائية عالية - يمكنه فصل تيارات العطل الهائلة دون انفجار. لكن لديه تصنيف Icw قليل أو معدوم. عندما يتجاوز تيار العطل إعداد الفصل الفوري الخاص به، فإنه عليك يفصل على الفور. لا يوجد تأخير. لا يوجد انتظار لمعرفة ما إذا كان القاطع الموجود في اتجاه المصب سيتعامل معه أولاً.

أن ICCB (قاطع الدائرة ذو العلبة المعزولة) لديه أيضًا قدرة فصل عالية. ولكن إليك ما يغير قواعد اللعبة: لديه تصنيف Icw كبير - القدرة على حمل تيار عطل هائل لمدة محددة (عادةً من 0.05 إلى 1 ثانية) دون فصل ودون تلف. فكر في الأمر على أنه قدرة القاطع على حبس أنفاسه تحت الماء بينما يقوم القاطع الموجود في اتجاه المصب بعمله.

وفقًا للمعيار IEC 60947-2:2024 - المعيار الذي يحكم قواطع الدائرة ذات الجهد المنخفض - ينقسم عالم القواطع إلى معسكرين:

- الفئة أ: لا يوجد تأخير زمني قصير متعمد. يجب أن يفصل بسرعة. قواطع MCCB تعيش هنا.

- الفئة ب: مصممة للانتقائية مع تحمل زمني قصير متعمد. قواطع ICCB و قواطع الهواء (ACBs) تعيش هنا.

لماذا هذا مهم؟ لأنه بدون تصنيف Icw، لا يمكنك الحصول على انتقائية حقيقية. وبدون انتقائية، يمكن لعطل في أي مكان في منشأتك أن يفصل القاطع الرئيسي الخاص بك.

دعني أرسم لك صورة.

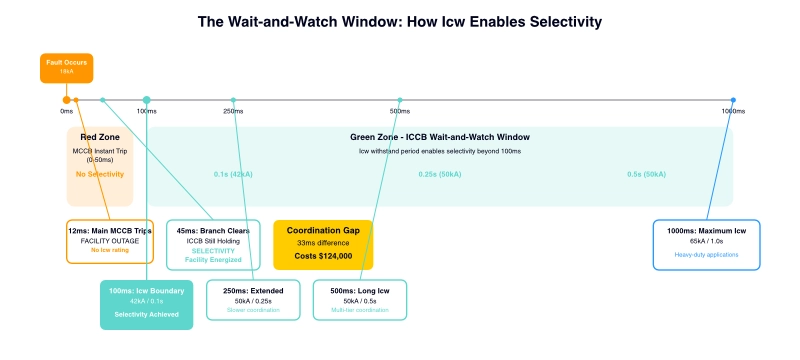

القاطع الرئيسي الوارد ICCB الخاص بك مصنف عند 630 أمبير مستمر، مع Icw يبلغ 42 كيلو أمبير لمدة 0.1 ثانية. يحدث عطل في دائرة فرعية في اتجاه المصب، مما يولد 18 كيلو أمبير من تيار الدائرة القصيرة. يرى قاطع MCCB الفرعي العطل ويفصل في 45 مللي ثانية - في غضون نافذة الانتظار والمراقبة التي تبلغ 0.1 ثانية لقاطع ICCB. يحمل قاطع ICCB هذا التيار البالغ 18 كيلو أمبير لمدة 45 مللي ثانية دون شكوى، ويبقى مغلقًا، وتبقى منشأتك مزودة بالطاقة باستثناء الدائرة المعطلة. هذا هو قاتل التتالي في العمل - تصنيف Icw الذي يمنع حالات الفشل المتتالية.

الآن استبدل قاطع ICCB هذا بقاطع MCCB في الموضع الرئيسي. نفس العطل البالغ 18 كيلو أمبير في الفرع. لا يزال القاطع الفرعي يحاول إزالته في 45 مللي ثانية. لكن قاطع MCCB الرئيسي الخاص بك، بدون تصنيف Icw وبدون تأخير زمني، يرى 18 كيلو أمبير، ويقرر أن هذا يتجاوز عتبة الفصل الفوري الخاصة به، ويفصل في 12 مللي ثانية. تنقطع الكهرباء عن المنشأة بأكملها. لا يحصل القاطع الفرعي على فرصته أبدًا.

هذا هو الفرق الذي كلفك 124000 دولار أمريكي.

لماذا تخلق قواطع MCCB حالات فشل متتالية (فخ الفصل الفوري)

إليك المفارقة التي يواجهها المهندسون: السرعة جيدة عادةً في حماية الدائرة. كلما قمت بإزالة العطل بشكل أسرع، قل الضرر الذي يلحق بالمعدات، وزادت السلامة للأفراد. تتفوق قواطع MCCB في هذا - فهي مصممة للفصل بسرعة عند حدوث الأعطال.

لكن السرعة تصبح مسؤولية عندما تكون في قمة التسلسل الهرمي للتوزيع.

هذا هو فخ الفصل الفوري: قاطع MCCB الخاص بك يفعل بالضبط ما صُمم لفعله - الحماية من تيار العطل العالي عن طريق الفتح الفوري. لسوء الحظ، هذا يعني أنه لا يمكنه التمييز بين “هذا هو العطل الذي يجب علي إزالته” و “يجب أن يتعامل جهاز في اتجاه المصب مع هذا”. يرى تيارًا عاليًا، ويفصل. لا توجد أسئلة.

الأرقام تحكي القصة. في مثالنا السابق، فصل قاطع MCCB الرئيسي في 12 مللي ثانية. احتاج قاطع MCCB الفرعي الموجود في اتجاه المصب إلى 45 مللي ثانية لإزالة العطل. فاز القاطع الرئيسي بالسباق - وفقدت منشأتك بأكملها الطاقة نتيجة لذلك.

لا يمكنك تنسيق ما لا يمكنك تأخيره.

يقر المعيار IEC 60947-2:2024 بهذا القيد صراحةً. تصنف قواطع MCCB على أنها أجهزة من الفئة A: “قواطع الدائرة غير مخصصة تحديدًا للانتقائية في ظل ظروف الدائرة القصيرة.” يخبرك المعيار، بلغة رسمية، أن قواطع MCCB في الموضع الرئيسي تمثل خطرًا للتنسيق.

تحل قواطع ICCB هذه المشكلة من خلال نافذة الانتظار والمراقبة- هذا التأخير الزمني الذي يدعم Icw. قد يكون لقاطع ICCB النموذجي تصنيف Icw يبلغ 42 كيلو أمبير لمدة 0.1 ثانية، أو 50 كيلو أمبير لمدة 0.5 ثانية. خلال تلك النافذة، يمكن لقاطع ICCB حمل تيار العطل دون فصل، مما يمنح القواطع الموجودة في اتجاه المصب وقتًا للعمل. ال جهات الاتصال لا تلتحم، ولا يتشقق الغلاف، ولا ترتفع درجة حرارة القضبان - فهي مصممة لتحمل كل من الإجهاد الحراري والقوى الكهرومغناطيسية لهذا الاندفاع الهائل للتيار.

لنكن محددين بشأن ما تعنيه كلمة “تحمل”. عندما يتدفق 42000 أمبير عبر جهات اتصال مصممة للتشغيل المستمر عند 630 أمبير، تكون القوى الكهرومغناطيسية هائلة - تخيل محاولة إبقاء مغناطيسين قويين منفصلين بينما يحاولان الارتطام ببعضهما البعض. الحمل الحراري شديد - هذا القدر من التيار يولد حرارة خطيرة حتى على مدى 0.1 ثانية. تم تصميم البناء الميكانيكي لقاطع ICCB، وآلية التشغيل المخزنة للطاقة، وتصميم الاتصال القوي، كلها للبقاء على قيد الحياة في هذا الاعتداء. قاطع MCCB؟ ستلتحم جهات الاتصال الخاصة به، أو ستفشل آلية الفصل الخاصة به، أو على الأقل ستفصل لحماية نفسها.

في سيناريو الفشل المتتالي الخاص بنا، إليك كيف يبدو الانتقاء المناسب:

- الوقت 0 مللي ثانية: يحدث عطل في اللوحة 3B. تيار الدائرة القصيرة: 18 كيلو أمبير.

- الوقت 12 مللي ثانية: يبدأ قاطع MCCB الفرعي في اللوحة 3B في فتح جهات الاتصال الخاصة به.

- الوقت 45 مللي ثانية: قاطع MCCB الفرعي يزيل العطل بالكامل. يعود التيار إلى الصفر.

- قاطع ICCB الرئيسي: حمل 18 كيلو أمبير لمدة 45 مللي ثانية (أقل بكثير من تصنيفه البالغ 0.1 ثانية، 42 كيلو أمبير). لم يفصل أبدًا. تبقى المنشأة مزودة بالطاقة.

هذا هو التنسيق. هذا ما تشتريه مقابل 7000 دولار أمريكي.

MCCB مقابل ICCB: مقارنة فنية كاملة

دعنا نحلل كل بُعد فني تختلف فيه هذه القواطع - ولماذا تهم هذه الاختلافات لتطبيقك.

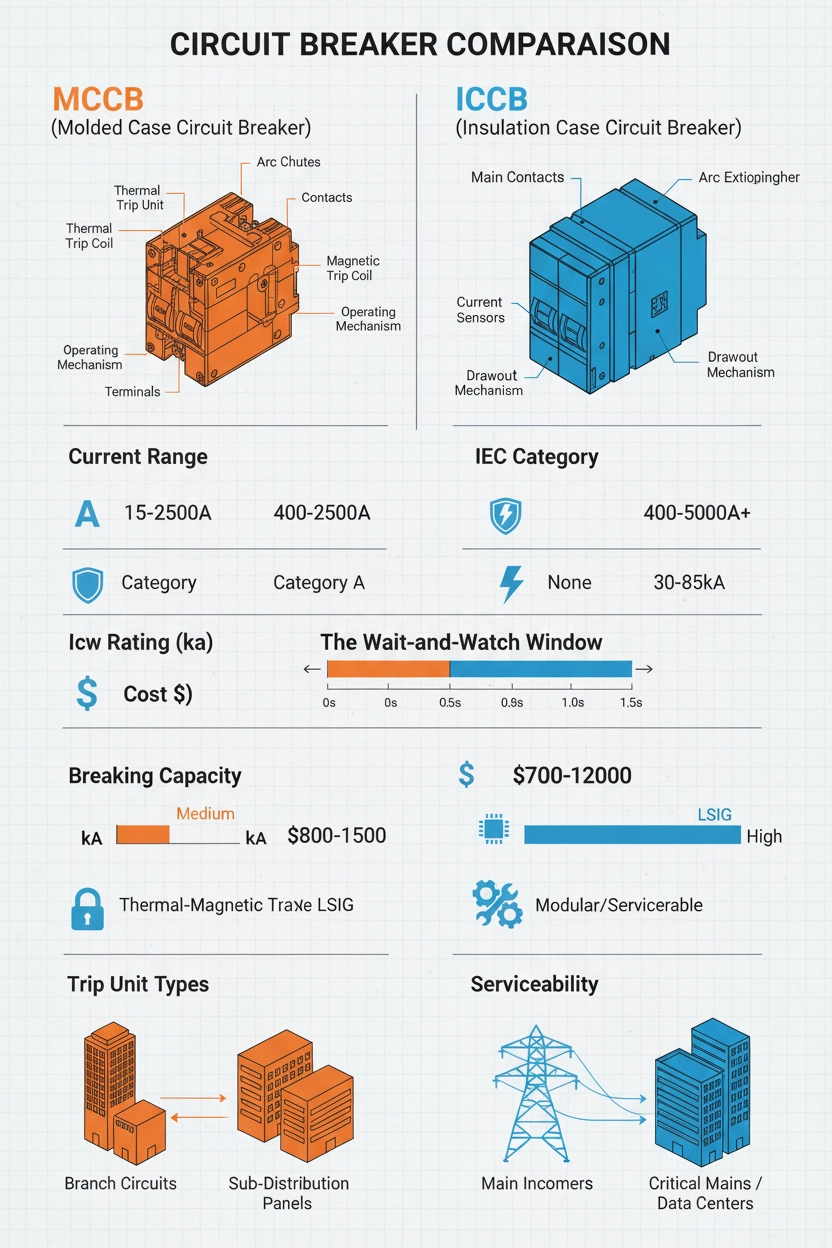

البناء وفلسفة التصميم

مركبات MCCBs مبنية مثل الخزانات المغلقة. آلية التشغيل بأكملها - جهات الاتصال، ومخمدات القوس، ووحدة الفصل، والوصلات - تعيش داخل علبة بلاستيكية أو راتنج مصبوبة. بمجرد التصنيع، يكون القاطع غير قابل للخدمة بشكل أساسي. إذا فشلت وحدة الفصل، أو إذا تآكلت جهات الاتصال، فإنك تستبدل الوحدة بأكملها. هذا يحافظ على انخفاض التكاليف ويجعل التثبيت بسيطًا. بالنسبة لقاطع MCCB بقدرة 400 أمبير، فأنت تبحث عن 800 دولار أمريكي إلى 1500 دولار أمريكي. البصمة المدمجة هي ميزة رئيسية في اللوحات ذات المساحات المحدودة.

قواطع ICCB تتبع نهجًا مختلفًا. يتم بناؤها بتصميم معياري قوي داخل غلاف عازل قوي. الميزة الرئيسية هي آلية تخزين الطاقة على خطوتين - نظام مشحون بنابض يوفر فصلًا قويًا وسريعًا للاتصال حتى في ظل ظروف العطل العالية. جهات الاتصال ووحدات الفصل وبعض المكونات الميكانيكية قابلة للاستبدال في الموقع. بالنسبة لقاطع ICCB مماثل بقدرة 630 أمبير، فأنت تبحث عن 7000 دولار أمريكي إلى 12000 دولار أمريكي في البداية. ولكن عندما تحتاج وحدة الفصل الإلكترونية إلى الاستبدال بعد 15 عامًا؟ هذا استبدال لوحدة فصل بقيمة 2000 دولار أمريكي بدلاً من استبدال قاطع بقيمة 10000 دولار أمريكي. البصمة المادية أكبر بكثير - هذه أجهزة من فئة المفاتيح الكهربائية.

إذا كنت تحسب تكاليف دورة الحياة، فإن ميزة الصيانة في قواطع التيار المعزولة (ICCBs) تصبح كبيرة. لنفترض أن لديك مغذيًا رئيسيًا حرجًا يعمل لمدة 25 عامًا. قد يحتاج قاطع التيار المقولب (MCCB) إلى استبدال كامل واحد (1500 وحدة نقدية) في منتصف العمر بسبب تآكل التلامس. قد يحتاج قاطع التيار المعزول (ICCB) إلى استبدال وحدة فصل واحدة (2000 وحدة نقدية) ومجموعة واحدة من مجموعات التلامس (1200 وحدة نقدية). فرق التكلفة الأولية: 8000 وحدة نقدية. فرق صيانة دورة الحياة: 1700 وحدة نقدية. على مدى 25 عامًا، تضيق الفجوة.

ولكن إليك ما لا يمكنك وضع سعر عليه: عندما يكون لدى قاطع التيار الرئيسي المعزول (ICCB) فشل في وحدة الفصل، فإنك تستبدل وحدة الفصل خلال فترة صيانة مجدولة - ربما ساعتين من التوقف. عندما يفشل قاطع التيار الرئيسي المقولب (MCCB)؟ أنت تبحث عن شراء طارئ، وشحن سريع (إذا كنت محظوظًا)، وانقطاع غير مخطط له قد يستمر من 8 إلى 24 ساعة اعتمادًا على مخزون الموزع. هذا هو ضريبة الانتقائية تظهر في شكل مختلف - التكلفة الخفية للمعدات غير القابلة للصيانة في المواقع الحرجة.

تصنيف Icw: تأمين الانتقائية الخاص بك

هذا هو المكان الذي تكسب فيه قواطع التيار المعزولة (ICCBs) قيمتها.

قواطع التيار المقولبة (MCCBs)، كأجهزة من الفئة A وفقًا للمعيار IEC 60947-2:2024، ليس لديها تصنيف Icw منشور. قد يكون لدى بعض قواطع التيار المقولبة (MCCBs) ذات الإطار الأكبر (أكثر من 1000 أمبير) قدرة محدودة على التحمل لفترة قصيرة، لكنها ليست معلمة مصنفة أو تم اختبارها أو مضمونة. بالنسبة لمعظم قواطع التيار المقولبة (MCCBs) حتى 630 أمبير، فإن Icw يساوي صفرًا بشكل فعال - يجب أن تفصل على الفور عندما يتجاوز تيار القصر إعدادها اللحظي.

قواطع التيار المعزولة (ICCBs)، كأجهزة من الفئة B، مصممة ومختبرة خصيصًا لتحمل التيار لفترة قصيرة. تشمل تصنيفات Icw الشائعة ما يلي:

- 42 كيلو أمبير لمدة 0.1 ثانية (شائع لإطارات 630-800 أمبير)

- 50 كيلو أمبير لمدة 0.5 ثانية (قواطع التيار المعزولة (ICCBs) متوسطة التحمل)

- 65 كيلو أمبير لمدة 1.0 ثانية (قواطع التيار المعزولة (ICCBs) شديدة التحمل لبيئات الأعطال الشديدة)

هذه ليست ادعاءات تسويقية - هذه تصنيفات تم اختبارها والتحقق منها وفقًا للمعيار IEC 60947-2. أثناء الاختبار، يتعرض القاطع لتيار Icw المقدر للمدة المحددة أثناء إبقائه مغلقًا (بدون عملية فصل). بعد الاختبار، يجب ألا يظهر على القاطع أي تلف، ويحافظ على تحمله العازل، ويستمر في العمل ضمن المواصفات.

نافذة الانتظار والمراقبة هي الطريقة التي يجب أن تفكر بها في هذا التصنيف. إذا كان لدى قاطع التيار المعزول (ICCB) الخاص بك Icw بقيمة 42 كيلو أمبير لمدة 0.1 ثانية، فيمكنك تعيين تأخير قصير المدى يصل إلى 0.1 ثانية، وسوف ينجو القاطع من أي تيار عطل يصل إلى 42 كيلو أمبير خلال تلك الفترة. هذا يمنح قواطع التيار المتصلة بالأسفل - والتي عادة ما تفصل في 20-80 مللي ثانية اعتمادًا على حجم العطل ونوع القاطع - وقتًا للعمل أولاً.

إليك كيفية تحديد حجم Icw لنظامك:

- احسب تيار القصر المحتمل في موضع القاطع الرئيسي. إذا كنت تتغذى من محول 1000 كيلو فولت أمبير بمعاوقة 6٪ عند 400 فولت، فإن تيار العطل المتاح لديك يبلغ حوالي 36 كيلو أمبير. أنت بحاجة إلى تصنيف Icw أعلى من هذه القيمة.

- حدد أوقات فصل قاطع التيار المتصل بالأسفل. بالنسبة لقواطع التيار المقولبة (MCCBs) في نطاق 100-630 أمبير التي تفصل الأعطال في منطقة الفصل المغناطيسي الخاصة بها، توقع وقت فصل 20-50 مللي ثانية. بالنسبة لمستويات الأعطال الأعلى التي تقترب من تصنيف Icu الخاص بها، تمتد أوقات الفصل إلى 50-100 مللي ثانية.

- أضف هامش أمان وحدد مدة Icw. إذا كان أبطأ قاطع تيار متصل بالأسفل يفصل في 80 مللي ثانية، فحدد مدة Icw لا تقل عن 0.1 ثانية (100 مللي ثانية). الممارسة الشائعة هي خطوة زمنية واحدة فوق متطلباتك المحسوبة. إذا كانت 0.1 ثانية هامشية، فحدد 0.25 ثانية أو 0.5 ثانية.

- اضبط التأخير قصير المدى. مع تصنيف Icw بقيمة 42 كيلو أمبير / 0.1 ثانية وتيار عطل محسوب يبلغ 36 كيلو أمبير، يمكنك تعيين تأخير قصير المدى يبلغ 0.1 ثانية بأمان على قاطع التيار المعزول (ICCB) الخاص بك، مع العلم أنه سينجو حتى يفصل الجهاز المتصل بالأسفل العطل.

هذا الحساب هو قاتل التتالي قيد التنفيذ - هندسة الانتقائية في نظامك بدلاً من الأمل في ذلك.

وحدات الفصل: حرارية مغناطيسية مقابل معالج دقيق LSIG

مركبات MCCBs تأتي عادةً مع أحد نوعي وحدات الفصل:

- حرارية مغناطيسية: شريط ثنائي المعدن للحماية من الحمل الزائد (الجزء “الحراري”) وملف كهرومغناطيسي للحماية من قصر الدائرة (الجزء “المغناطيسي”). القدرة على التعديل محدودة - ربما قرص لضبط النقطة المحددة الحرارية في حدود ±20٪. هذه قوية وموثوقة ولا تحتاج إلى صيانة. كما أنها ليست ذكية جدًا.

- إلكترونية أساسية: وحدة فصل تعتمد على معالج دقيق مع قدر أكبر من التعديل - ربما إعدادات طويلة المدى (L) ولحظية (I). يمكنك الحصول على تحديد المنحنى، وربما حماية من الأعطال الأرضية في الطرز المتطورة. أفضل من الحرارية المغناطيسية، ولكن لا تزال محدودة مقارنة بقواطع التيار المعزولة (ICCBs).

قواطع ICCB تستخدم حصريًا تقريبًا وحدات فصل متقدمة تعتمد على معالج دقيق مع كامل LSIG الحماية - فكر في الأمر على أنه سكين الجيش السويسري لحماية الدائرة:

- L (طويل المدى): حماية من الحمل الزائد. نقطة محددة قابلة للتعديل (عادةً 0.4-1.0 × In)، وتأخير زمني قابل للتعديل. هذا هو منحنى الحمل الزائد الحراري الخاص بك.

- S (قصير المدى): هذه هي نافذة الانتظار والمراقبة. نقطة محددة قابلة للتعديل (عادةً 1.5-10 × In)، وتأخير زمني قابل للتعديل (0.05-1.0 ثانية). هذه هي أداة الانتقائية الخاصة بك.

- I (لحظي): فصل فائق السرعة لتيارات الأعطال العالية جدًا. نقطة محددة قابلة للتعديل (عادةً 3-15 × In)، بدون تأخير مقصود. هذا هو إعداد “هناك خطأ كبير، افتح الآن”.

- G (عطل أرضي): كشف منفصل للأعطال الأرضية مع نقطة محددة خاصة به وتأخير زمني. أمر بالغ الأهمية لسلامة الأفراد ومنع حرائق الأعطال الأرضية.

لماذا يهم هذا التعديل؟ لأن كل نظام كهربائي فريد من نوعه. قد يكون تيار الاندفاع لبدء تشغيل المحرك الخاص بك 6 × In. قد تتطلب دراسة التنسيق المتصلة بالأسفل تأخيرًا قدره 0.2 ثانية عند 8 × In. تحتاج حماية الأعطال الأرضية الخاصة بك إلى التنسيق مع قواطع التيار الأرضي (GFCIs) المتصلة بالأسفل. تتيح لك وحدة الفصل LSIG تحديد الحماية والتنسيق اللذين يتطلبهما نظامك بالضبط.

مع وحدة الفصل الأساسية لقاطع التيار المقولب (MCCB)، فأنت عالق بإعدادات المصنع أو تعديل محدود للغاية. قد تحدد نموذج قاطع مختلف بمنحنى فصل مختلف وتأمل أن ينجح. مع قاطع التيار المعزول (ICCB)، يمكنك برمجة الحماية التي تحتاجها بالضبط.

وإليك ميزة عملية: عندما يتغير نظامك - عندما تضيف محرك أقراص متغير التردد (VFD) كبيرًا يغير ملف تعريف تيار العطل الخاص بك، أو عندما تضيف دوائر متصلة بالأسفل تتطلب تنسيقًا مختلفًا - يمكنك إعادة برمجة وحدة فصل قاطع التيار المعزول (ICCB). مع قاطع التيار المقولب (MCCB)، قد تقوم باستبدال القواطع.

تصنيفات التيار ونطاق التطبيق

مركبات MCCBs تغطي النطاق من 15 أمبير حتى 2500 أمبير. نقطة قوتها هي 15-1600 أمبير، حيث تهيمن على التوزيع الفرعي ومراكز التحكم في المحركات وحماية دائرة الفرع. في الطرف العلوي (1600-2500 أمبير)، أنت تنظر إلى قواطع التيار المقولبة (MCCBs) المتخصصة والكبيرة الحجم التي تطمس الخط الفاصل مع قواطع التيار المعزولة (ICCBs) - لكنها لا تزال أجهزة من الفئة A بدون تصنيفات Icw ذات مغزى.

قواطع ICCB تبدأ عادةً من 400 أمبير وتمتد إلى 5000 أمبير أو أعلى. نية تصميمها هي التوزيع الرئيسي - معدات مدخل الخدمة، والمفاتيح الرئيسية، وقواطع الربط، وحماية المغذيات الحرجة حيث تكون الانتقائية والموثوقية ذات أهمية قصوى. أقل من 400 أمبير، قواطع التيار المعزولة (ICCBs) نادرة؛ فوق 2500 أمبير، تبدأ في إفساح المجال لقواطع التيار الهوائية (ACBs)، التي توفر تصنيفات أعلى وحتى خدمة سحب كاملة.

هناك منطقة تداخل: 400-2500 أمبير. في هذا النطاق، يمكنك تحديد إما قاطع التيار المقولب (MCCB) أو قاطع التيار المعزول (ICCB). معايير القرار الخاصة بك:

- مغذي رئيسي أو توزيع رئيسي حرج؟ ← قاطع التيار المعزول (ICCB)

- هل تحتاج إلى انتقائية حقيقية مع الأجهزة المتصلة بالأسفل؟ ← قاطع التيار المعزول (ICCB)

- توزيع فرعي أو مغذي غير حرج؟ ← قاطع التيار المقولب (MCCB) يوفر التكلفة

- تيار العطل المحتمل للنظام > 30 كيلو أمبير ويتطلب التنسيق؟ ← قاطع التيار المعزول (ICCB)

- لوحة محدودة المساحة؟ ← قاطع التيار المقولب (MCCB) أكثر إحكاما

أقل من 400 أمبير، عادةً ما يكون قاطع التيار المقولب (MCCB) هو خيارك العملي الوحيد ما لم تكن على استعداد لتكبير حجم قاطع التيار المعزول (ICCB) بشكل كبير. فوق 2500 أمبير، يصبح قاطع التيار المعزول (ICCB) إلزاميًا للحصول على توفر وأداء لائقين.

جدول المقارنة

| المعلمة | MCCB | قاطع التيار المعزول (ICCB) |

|---|---|---|

| النطاق الحالي | 15-2500 أمبير | 400-5000 أمبير + |

| فئة IEC | الفئة A (بدون نية الانتقائية) | الفئة ب (انتقائية بالتصميم) |

| تصنيف Icw | لا يوجد (أو غير مصنف) | 30-85 كيلو أمبير لمدة 0.05-1.0 ثانية |

| Breaking Capacity (Icu) | حتى 150 كيلو أمبير | حتى 150 كيلو أمبير + |

| وحدات الفصل | حراري-مغناطيسي أو إلكتروني أساسي | معالج دقيق LSIG (قابل للتعديل بالكامل) |

| تأخير زمني قصير | غير متوفر | قابل للتعديل 0.05-1.0 ثانية |

| الإنشاءات | مغلقة، غير قابلة للصيانة | معيارية، قابلة للصيانة ميدانيًا |

| التكلفة النموذجية (630 أمبير) | $800-$1,500 | $7,000-$12,000 |

| الحجم المادي | مدمجة | كبير (فئة المفاتيح الكهربائية) |

| قابلية الخدمة خلال دورة الحياة | استبدال الوحدة بأكملها | استبدال وحدة الفصل أو الملامسات |

| تطبيق نموذجي | التوزيع الفرعي، الدوائر الفرعية | المغذيات الرئيسية، المغذيات الرئيسية الحيوية |

| قدرة التنسيق | محدودة (فصل سريع فقط) | ممتازة (تأخير زمني متاح) |

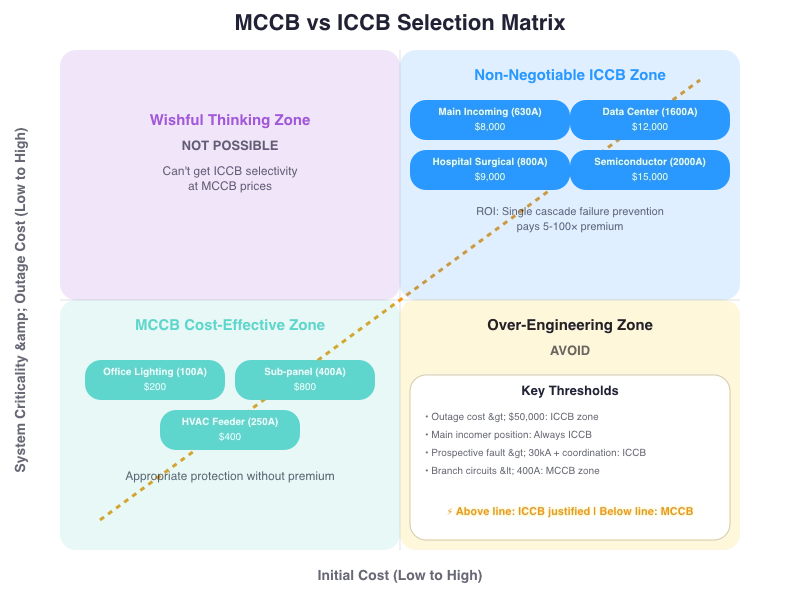

متى يتم استخدام MCCB مقابل ICCB: شجرة قرارات المهندس

لا يتعلق الاختيار بين MCCB و ICCB بالمواصفات بمعزل عن غيرها - بل يتعلق بمطابقة قدرات القاطع لمتطلبات النظام وأولويات العمل.

الخطوة 1: حدد موقع التطبيق الخاص بك

السؤال الأول هو سؤال تراتبي: أين يقع هذا القاطع في نظام التوزيع الخاص بك؟

قاطع خدمة الدخول الرئيسي؟ هذه منطقة ICCB. أنت تحمي المنشأة بأكملها، والفصل هنا يعني الظلام الدامس. تصنيف Icw ليس اختياريًا - إنه بوليصة التأمين الخاصة بك ضد حالات الفشل المتتالي. حتى إذا كنت تدير منشأة صغيرة نسبيًا (خدمة 400 أمبير)، فإن عواقب فصل القاطع الرئيسي تبرر عادةً علاوة ICCB.

قواطع التوزيع الفرعي أو المغذيات الكبيرة؟ أنت الآن في منطقة القرار. إذا كان هذا القاطع يحمي عملية حيوية (مركز بيانات، جناح جراحة في مستشفى، غرفة نظيفة لأشباه الموصلات)، فإن مزايا الانتقائية والموثوقية في ICCB ترجح الكفة. إذا كان يغذي إضاءة مكتبية قياسية أو أحمال غير حيوية، فمن المحتمل أن يكون MCCB جيدًا.

دائرة فرعية أو حماية المحرك؟ MCCB هو إجابتك. أقل من 400 أمبير وتغذية أحمال الاستخدام النهائي، لا يمكن تبرير علاوة التكلفة لـ ICCB. يتفوق MCCBs في هذا الدور - فهي فعالة من حيث التكلفة ومضغوطة وتوفر حماية ممتازة للدوائر الفرعية.

قاعدة عامة: إذا تسبب الفصل في موقع هذا القاطع في انقطاع التيار الكهربائي على مستوى المنشأة أو أدى إلى إيقاف تشغيل الأنظمة الحيوية، فأنت بحاجة إلى قدرة الانتقائية في ICCB.

الخطوة 2: احسب ضريبة الانتقائية

لنتحدث عن المال.

علاوة ICCB على MCCB المكافئ: من 6000 دولار إلى 10000 دولار للقواطع الرئيسية الداخلة النموذجية 630-1600 أمبير.

تكلفة فشل متتالي واحد: يعتمد هذا بشكل كبير على نوع المنشأة الخاصة بك:

- مصنع صغير (10 موظفين، 500 كيلو وات): من 35000 دولار إلى 75000 دولار لكل انقطاع لمدة 8 ساعات (فقدان الإنتاج، العمل الإضافي، تكاليف إعادة التشغيل)

- منشأة تصنيع متوسطة (50 موظفًا، 2 ميجاوات): من 100000 دولار إلى 250000 دولار لكل انقطاع لمدة 8 ساعات

- مركز بيانات أو عمليات تكنولوجيا المعلومات: 540000 دولار في الساعة (بناءً على متوسط الصناعة البالغ 9000 دولار / دقيقة)

- مناطق الرعاية الحرجة في المستشفى: لا يمكن قياسها من الناحية المالية البحتة (سلامة المرضى)، ولكن التقديرات تتراوح من 50000 دولار إلى 200000 دولار في الساعة في تعطيل العمليات

- مصنع أشباه الموصلات أو عملية مستمرة: من 500000 دولار إلى 2000000 دولار لكل انقطاع (تلف المعدات، فقدان الدفعات، دورات إعادة التشغيل)

قم بإجراء العمليات الحسابية لمنشأتك. قم بتقدير قيمة الإنتاج بالساعة، وأضف تكاليف الخردة / إعادة التشغيل، وأضف علاوة العمل الإضافي، وأضف تكاليف الصيانة الطارئة. الآن اضرب في متوسط مدة الانقطاع (عادةً 4-12 ساعة للفشل المتتالي، لأنك تستكشف سبب تعثر التيار الرئيسي بدلاً من مجرد إعادة ضبط قاطع الدائرة الفرعية).

حساب العائد:

إذا منع ICCB فشلًا متتاليًا واحدًا فقط في عمره البالغ 25 عامًا، فإنه يسدد تكلفته من 5 إلى 100 مرة، اعتمادًا على منشأتك. وإليك الأمر المثير: المنشأة التي تعاني من ضعف الانتقائية لا تشهد فشلًا متتاليًا واحدًا في 25 عامًا. عادةً ما ترى 3-10 أحداث متتالية قبل أن يقوم شخص ما أخيرًا بترقية القاطع الرئيسي. بحلول ذلك الوقت، تكون قد دفعت ضريبة الانتقائية مرارا وتكرارا.

تبدأ علاوة ICCB البالغة 8000 دولار في الظهور وكأنها صفقة رابحة.

الخطوة 3: تحقق من تيار العطل ودراسة التنسيق الخاصة بك

الفحص الفني النهائي: هل يحتاج نظامك حتى إلى قدرة التنسيق التي يوفرها ICCB؟

احسب تيار الدائرة القصيرة المحتمل عند القاطع الرئيسي. إذا كنت تتغذى من محول صغير (100 كيلو فولت أمبير أو أقل) مع مقاومة مصدر كبيرة، فقد يكون تيار العطل المتاح لديك 8-12 كيلو أمبير فقط. في هذه المستويات، حتى MCCBs لديها أوقات فصل مغناطيسي بطيئة نسبيًا، وقد يكون التنسيق الأساسي من خلال حجم التيار وحده ممكنًا. قد لا تحتاج إلى تنسيق قائم على الوقت.

ولكن إليك الواقع: معظم المرافق التجارية والصناعية لديها تيارات عطل محتملة تبلغ 20-50 كيلو أمبير في التوزيع الرئيسي. في هذه المستويات، تتعثر MCCBs في 10-20 مللي ثانية، مما لا يترك وقتًا للتنسيق في اتجاه المصب. أنت بحاجة إلى انتقائية التأخير الزمني. أنت بحاجة إلى نافذة الانتظار والمشاهدة. أنت بحاجة إلى ICCB.

راجع أوقات إزالة القاطع في اتجاه المصب. إذا كانت جميع قواطع التيار في اتجاه المصب سريعة المفعول MCBs أو MCCBs صغيرة تزيل في أقل من 30 مللي ثانية، فقد تتمكن من استخدام ICCB مع تأخير زمني قصير (0.05-0.1 ثانية) وتحقيق انتقائية كاملة. إذا كان لديك MCCBs أكبر في اتجاه المصب أو أجهزة أبطأ تستغرق 80-120 مللي ثانية للإزالة، فستحتاج إلى فترات Icw أطول (0.25-0.5 ثانية).

تحقق من أن تصنيف Icw الخاص بك يتجاوز تيار العطل المحتمل الخاص بك. إذا كان تيار العطل المحسوب لديك هو 38 كيلو أمبير، فلا تحدد ICCB بتصنيف 42 كيلو أمبير Icw وتعتبره جيدًا. هذا هامش بنسبة 10٪ - ضئيل للغاية. حدد 50 كيلو أمبير أو 65 كيلو أمبير Icw لحساب تقلب مساهمة عطل المرافق والتغييرات المستقبلية في النظام وهامش الأمان.

وإذا كنت تفكر الآن وتقول: “ليس لدينا دراسة تنسيق”—فهذه هي إجابتك. إذا كان مرفقك مهمًا بما يكفي للنظر في مسألة قاطع التيار المقولب (MCCB) مقابل قاطع التيار المعزول (ICCB)، فأنت بحاجة إلى دراسة للتيار القصير والتنسيق. إن قاطع التيار المعزول (ICCB) بدون دراسة تنسيق مناسبة يشبه شراء سيارة فيراري وعدم تجاوز الغيار الأول. لقد دفعت مقابل إمكانات لا تستخدمها. وعلى العكس من ذلك، فإن قاطع التيار المقولب (MCCB) في موقع رئيسي بدون دراسة هو فشل متتالي ينتظر الحدوث.

الخلاصة: الخيار الذي يمنع انقطاعات بقيمة 124,000 دولار

الفرق بين قواطع التيار المقولبة (MCCBs) وقواطع التيار المعزولة (ICCBs) ليس في قدرة الفصل، أو الحجم المادي، أو حتى التكلفة. بل هو الانتقائية.

قواطع التيار المقولبة (MCCBs) هي أجهزة من الفئة A—حماية سريعة وموثوقة وفعالة من حيث التكلفة لدوائر الفروع والتوزيع الفرعي. إنها تتفوق في هذه الأدوار. ولكن في موقع الدخول الرئيسي، فإن افتقارها إلى تصنيف Icw يعني أنها تقع في فخ الفصل الفوري: لا يمكنها التمييز بين الأعطال التي يجب أن تفصلها والأعطال التي يجب أن تتعامل معها الأجهزة الموجودة في اتجاه المصب. تصبح السرعة عبئًا.

قواطع التيار المعزولة (ICCBs) هي أجهزة من الفئة B—مصممة خصيصًا للانتقائية في الجزء العلوي من التسلسل الهرمي للتوزيع. قاتل التتالي يمنحها تصنيف Icw نافذة الانتظار والمراقبة: القدرة على حمل تيار عطل هائل لمدة 0.05-1.0 ثانية دون التعثر، مما يسمح لقواطع التيار الموجودة في اتجاه المصب بفصل الأعطال أولاً. توفر وحدات الفصل LSIG المتقدمة منحنيات حماية دقيقة وقابلة للتعديل. يتيح البناء المعياري الصيانة الميدانية بدلاً من الاستبدال الكامل.

القسط؟ 6,000 دولار - 10,000 دولار لقاطع تيار دخول رئيسي نموذجي.

العائد؟ عدم تعثر المرفق بأكمله عندما يكون هناك عطل في اللوحة 3B.

إليك إطار اتخاذ القرار:

- قواطع خدمة الدخول الرئيسية: قاطع التيار المعزول (ICCB). غير قابل للتفاوض إذا كنت تهتم بوقت التشغيل.

- المغذيات الحرجة (مراكز البيانات والمستشفيات والعمليات المستمرة): قاطع التيار المعزول (ICCB). ضريبة الانتقائية من فشل متتالي واحد يتجاوز قسط قاطع التيار.

- التوزيع الفرعي والمغذيات القياسية: قاطع التيار المقولب (MCCB) عادة ما يكون كافيًا ما لم تكشف دراسة التنسيق عن مشاكل.

- دوائر الفروع أقل من 400 أمبير: قاطع التيار المقولب (MCCB). فعال من حيث التكلفة ومناسب.

وإذا كنت لا تزال مترددًا بشأن قسط قاطع التيار المعزول (ICCB) البالغ 8,000 دولار، ففكر في هذا: السؤال ليس “هل يمكنني تحمل تكلفة قاطع التيار المعزول (ICCB)؟”

بل هو “هل يمكنني تحمل انقطاع آخر بقيمة 124,000 دولار؟”

راجع مواصفات قاطع الدخول الرئيسي الخاص بك اليوم. إذا كان قاطع تيار مقولب (MCCB) وليس لديك تصنيف Icw، فأنت على بعد عطل واحد في اتجاه المصب من الدفع ضريبة الانتقائية. مرة أخرى.

توقف عن دفع ضريبة الانتقائية. استثمر في قاتل التتالي. يعتمد وقت تشغيل مرفقك على ذلك.