Vamos começar com um cenário que vi na semana passada. São 18h. O disjuntor da cozinha desarma. De novo.

O micro-ondas, a chaleira e a torradeira estavam todos ligados. Você suspira, caminha até o quadro e rearma o disjuntor C-16 (16 Amperes).

Você volta para a cozinha, e a parte “consertadora” do seu cérebro entra em ação com um pensamento aparentemente lógico:

“Este disjuntor C-16 é uma porcaria. É muito fraco. Se eu simplesmente trocá-lo por um C-20 ou C-32 ‘mais forte’, isso vai parar com esses disparos incômodos.”

Pare.

Como engenheiro sênior, minha resposta a essa pergunta não é apenas “não”. É um “absolutamente-não-nem-pense-nisso-você-está-prestes-a-incendiar-sua-casa” NÃO.

Esta é, sem dúvida, uma das ideias erradas mais perigosas e mais comuns em segurança elétrica. Você não está “atualizando” seu disjuntor. Você está acendendo o pavio de um incêndio dentro de suas paredes.

Você não está enfrentando um disjuntor “ruim”. Você está enfrentando um bom disjuntor que está fazendo seu trabalho, e você está prestes a “demiti-lo” por ser um cão de guarda diligente.

Vamos falar sobre o que realmente está acontecendo.

1. O Contrato Disjuntor-Fio: O Pacto Que Salva Sua Casa

Aqui está o conceito mais importante que você precisa entender:

Um disjuntor não é projetado para proteger seus aparelhos. Ele é projetado para proteger os fios fios em suas paredes.

Pense no disjuntor (como um MCB VIOX C-16) e no fio de cobre em sua parede como tendo um “Contrato Disjuntor-Fio”.” É um pacto legal, escrito em todos os códigos elétricos, que diz:

“Eu, o Disjuntor C-16, juro solenemente morrer (desarmar) no instante em que a corrente elétrica ultrapassar 16 Amperes por muito tempo. Farei isso para proteger meu parceiro, o Fio de 2,5mm², que me disse que pode apenas transportar com segurança 16 Amperes antes de superaquecer, derreter seu isolamento plástico e iniciar um incêndio.”

Este contrato é o coração da segurança da sua casa. O tamanho do fio determina a corrente nominal do disjuntor. Não o contrário.

- Um fio de 1,5mm² recebe um disjuntor de 10A.

- Um fio de 2,5mm² recebe um disjuntor de 16A (ou 20A em alguns códigos).

- Um fio de 4,0mm² recebe um disjuntor de 25A.

Esta é uma parceria não negociável.

2. O Incêndio de 19 Amperes: O Que Acontece Quando Você Quebra o Contrato

Agora, vamos simular seu cenário de “atualização”.

Você ignora o contrato. Você retira o disjuntor de 16A e encaixa um novo e brilhante disjuntor de 20A. Você “demitiu” o cão de guarda de 16A e contratou um de 20A que está meio adormecido.

No dia seguinte, você conecta seu micro-ondas (8A), chaleira (5A) e torradeira (6A).

Corrente Total: 19 Amperes.

Isto é o que acontece a seguir, em câmera lenta horripilante:

- Os 19 Amperes fluem do quadro para aquele fio de 2,5mm² em sua parede, que foi construído apenas para suportar 16A.

- O Fio Grita. O fio imediatamente começa a superaquecer. É como rodar o motor de um carro a 8.000 RPM na primeira marcha. Não é não projetado para isso. Sua temperatura interna do cobre sobe... 70°C... 80°C... 90°C...

- O Isolamento Derrete. A jaqueta de isolamento de PVC de plástico ao redor do fio, que é o que impede um incêndio, começa a amolecer, carbonizar e derreter.

- O Disjuntor Não Faz Nada. O novo disjuntor de 20A vê 19 Amperes e pensa: “19A é menor que 20A. Tudo bem por aqui! Não devo desarmar ainda.” Ele continua felizmente a deixar os 19 Amperes fluírem.

- O Incêndio Começa. O fio de cobre agora desencapado e em brasa faz contato com o outro fio desencapado (neutro) ou um pedaço do montante de madeira em sua parede. Um arco pisca. A madeira inflama.

Você agora tem um incêndio dentro de sua parede, e o disjuntor de 20A ainda não desarmou porque ainda não há “curto-circuito”, apenas um incêndio de 19 Amperes.

Isto é o que eu chamo de “O Incêndio de 19 Amperes.” Você criou uma “lacuna da morte” fatal entre o limite de 16A do fio e o limite de 20A do disjuntor.

Dica #1: Um disjuntor a disparar não é uma falha. É um aviso. O disjuntor é o seu “mensageiro de segurança” leal. Está a pensar em “matar o mensageiro” porque as notícias dele (que o seu circuito está sobrecarregado) são irritantes.

3. Decifrar o Seu Quadro: “Terrível” vs. “Sobrecarregado”

Então, se “atualizar” é um risco de incêndio, qual é o real problema?

Esse disjuntor de 16A está a disparar por um de dois motivos:

Causa 1: Simples Sobrecarga (O Problema “Barato”)

Este é o caso mais provável. Está simplesmente a exigir demais desse circuito único.

O circuito da sua cozinha é uma “autoestrada” de 16A. O seu frigorífico é de 3A. O seu micro-ondas é de 8A. A sua chaleira é de 5A. A sua torradeira é de 6A.

Não pode colocar 22A de “carros” (eletrodomésticos) numa “autoestrada” de 16A e não esperar um engarrafamento (um disparo). Isto é especialmente verdade para eletrodomésticos de aquecimento (chaleira, torradeira, micro-ondas), que consomem muita energia.

- A Solução: Mude os seus hábitos. Não ligue o micro-ondas e a chaleira ao mesmo tempo. Esta é uma correção “barata”, mas é a única segura sem nova cablagem.

Causa 2: Um “Quadro Terrível” (O Problema “Caro”)

Lembra-se daquela história do Reddit? O eletricista mencionou “muitos fios” num disjuntor. Este é um sinal de alerta para um “quadro terrível”.”

Esta é uma prática perigosa e não conforme chamada “Ligação Dupla.”

É quando um eletricista preguiçoso ou não qualificado, em vez de adicionar um novo disjuntor, simplesmente pega em dois (ou mais!) fios de circuito separados, torce-os juntos e enfia-os em um terminal de disjuntor de 16A.

Isto significa que o seu “circuito de cozinha de 16A” pode na verdade, ser a cozinha... e a sala de jantar... e as luzes da sala de estar... tudo amontoado num único disjuntor que foi feito apenas para a cozinha.

Não está apenas a sobrecarregá-lo com a sua torradeira. Está a sobrecarregá-lo com metade da casa.

Dica #2: O orçamento de 700 EUR do eletricista não era apenas para “trocar 4 disjuntores”. Era para realizar uma cirurgia elétrica: para desfazer a “ligação dupla”, identificar todos os circuitos “ilegais” fundidos e instalar novos, separados disjuntores para cada um. Esta é uma correção complexa, que exige muita mão de obra, mas correta .

4. Por que 20A Não é “Melhor” do que 16A

Vamos acabar com esta ideia errada de uma vez por todas.

Em engenharia, “melhor” não significa “maior”.” “Melhor” significa “corretamente combinado”.”

- Um disjuntor C-16A é a escolha “melhor” para um fio de 2,5 mm².

- Um disjuntor C-20A é a escolha “melhor” para um fio de 4,0 mm² (ou 2,5 mm² em alguns códigos, mas vamos ater-nos ao princípio).

Usar um disjuntor de 20A num fio classificado para 16A é como substituir o fusível de 10A no rádio do seu carro por um fusível de 30A do A/C.

O rádio vai “funcionar”? Sim.

O fusível de 30A vai “parar de queimar por incômodo”? Sim.

O que acontece quando o rádio tem uma pequena falha e deve teria queimado o fusível de 10A? Agora vai puxar 25A, derreter o seu próprio chicote de fios e incendiar o seu painel... tudo enquanto o fusível de 30A diz: “Não há problema aqui!”

Você removeu a proteção.

Dica #3: Trate a classificação de Ampères do seu disjuntor como um limite rígido, não uma sugestão. É a máxima proteção que o seu fios pode suportar. Nunca, jamais, “arredonde para cima”.”

O Que Você Deve Realmente Fazer

Se o seu disjuntor continua a disparar, aqui está o caminho seguro e lógico.

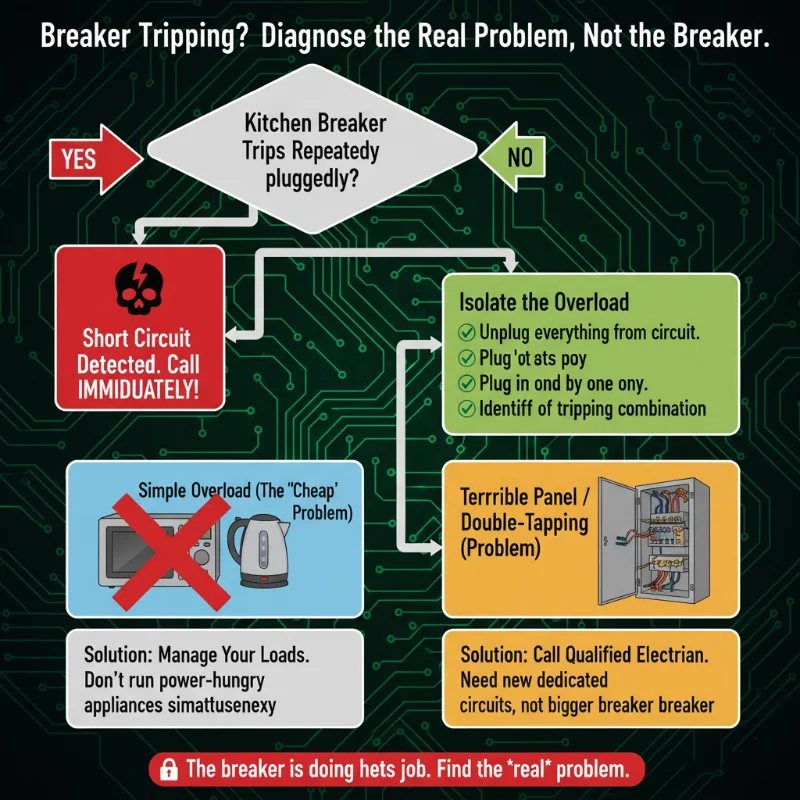

- Investigue. Desligue tudo desse circuito. Ligue o disjuntor novamente. Ele permanece ligado? Se sim, o disjuntor e o fio provavelmente estão bem. (Se disparar imediatamente com nada ligado, você tem um curto-circuito—chame um eletricista agora.)

- Isolar. Ligue um um aparelho de cada vez. Comece com o frigorífico. Espere. Agora o micro-ondas. Espere. Agora a chaleira. POP. Encontrou a combinação.

- Gerir. A sua única solução segura e gratuita é gerir as suas cargas. Nunca ligue a chaleira e o micro-ondas ao mesmo tempo.

- Obtenha uma Solução Real. O real solução é chamar um eletricista e dizer: “O circuito da minha cozinha está sobrecarregado. Preciso de passar um circuito novo e dedicado para o meu micro-ondas.” Eles passarão um novo fio separado do seu painel e dar-lhe-ão o seu própria novo disjuntor.

Sim, isso custa dinheiro. Mas não custa 700 EUR para substituir, e definitivamente não custa a sua casa inteira.

Não “atualize” o seu disjuntor. Atualize a sua cablagem.

O Rigor Técnico Nota

Normas E Fontes Referenciadas: Este artigo baseia-se nos princípios fundamentais da correspondência entre condutores e OCPD na IEC 60364 (“instalações elétricas de baixa tensão”) e nas normas regionais (como a NEC ou a BS 7671).

Isenção de responsabilidade: Os tamanhos dos fios (mm² ou AWG) e as suas classificações de disjuntor correspondentes (Amperes) variam consoante o país, o código e o material do condutor (cobre vs. alumínio). Siga sempre o seu código elétrico local e consulte um eletricista qualificado.

Pontualidade Instrução: Os princípios da proteção contra sobrecorrente são fundamentais e não mudam. Estes são precisos a partir de novembro de 2025.