A construction worker touches a faulty power drill. Current starts flowing through his body to ground—28 milliamps, then 35. Enough to stop his heart.

But before ventricular fibrillation begins, the circuit goes dead. The RCD in the temporary panel detected a 30 mA imbalance and disconnected power in 28 milliseconds. The worker drops the drill, shaken but alive. The MCB next to that RCD? It registered the fault current but did nothing—because this wasn’t its job. The current flowing through that worker’s body was tiny compared to what triggers an MCB, yet more than enough to kill.

This is the fundamental difference between RCD and MCB protection. RCDs detect tiny current leaks that can electrocute people. MCBs detect massive overcurrents that can melt wires and start fires. Same panel, different threats, completely different protection mechanisms.

Confusing these two devices—or worse, thinking one can substitute for the other—creates gaps in your electrical protection that can be fatal. This guide explains exactly how RCDs and MCBs work, when to use each, and why optimal safety often requires both working together.

RCD vs MCB: Quick Comparison

Before diving into technical details, here’s what separates these two essential protection devices:

| සාධකය | RCD (අවශේෂ ධාරා උපාංගය) | MCB (කුඩා පරිපථ කඩනය) |

|---|---|---|

| ප්රාථමික ආරක්ෂාව | Electric shock (protects people) | Overcurrent & short circuit (protects circuits) |

| Detects | Current imbalance between live and neutral (earth leakage) | Total current flowing through circuit |

| සංවේදීතාව | 10 mA to 300 mA (typically 30 mA for personnel protection) | 0.5A to 125A (circuit rating dependent) |

| ප්රතිචාර කාලය | 25-40 milliseconds at rated residual current | Thermal: seconds to minutes; Magnetic: 5-10 milliseconds |

| පරීක්ෂණ බොත්තම | Yes (must be tested quarterly) | පරීක්ෂණ බොත්තමක් නැත |

| ප්රමිතීන් | IEC 61008-1:2024 (RCCB), IEC 61009-1:2024 (RCBO) | IEC 60898-1:2015+A1:2019 |

| වර්ග | AC, A, F, B (based on waveform), S (time-delayed) | B, C, D (based on magnetic trip threshold) |

| Will NOT protect against | Overload or short circuit | Electric shock from earth leakage |

| Typical Application | Wet areas, socket outlets, construction sites, TT earthing | General circuit protection, lighting, power distribution |

Bottom line: An RCD without an MCB leaves your circuits vulnerable to overload and fire. An MCB without an RCD leaves people vulnerable to electric shock. You almost always need both.

What Is an RCD (Residual Current Device)?

අ Residual Current Device (RCD)—also called a Residual Current Circuit Breaker (RCCB) or Ground Fault Circuit Interrupter (GFCI) in North America—is an electrical safety device designed to prevent electric shock by detecting abnormal current flow to ground. Governed by IEC 61008-1:2024 for standalone RCCBs and IEC 61009-1:2024 for RCBOs (combined RCD+MCB), RCDs are mandatory in many jurisdictions for circuits where people may contact exposed conductive parts or operate equipment in wet conditions.

The “residual current” the device monitors is the difference between current flowing out through the live conductor and current returning through the neutral conductor. Under normal conditions, these two currents are equal—every electron that leaves must return through the neutral path. But when something goes wrong—a person touches a live wire, a tool casing becomes energized, insulation fails inside an appliance—some current finds an alternate path to ground. That imbalance is the residual current, and it’s what the RCD detects.

Here’s why RCDs save lives: Human muscle control is lost at approximately 10-15 mA of current through the body. Ventricular fibrillation (cardiac arrest) begins around 50-100 mA sustained for one second. A typical RCD for personnel protection is rated 30 mA with a trip time of 25-40 milliseconds. It disconnects the circuit before enough current flows for long enough to stop your heart.

RCDs do not protect against overcurrent or short circuits. If you overload a circuit protected only by an RCD—say, plugging a 3,000W heater into a 13A socket circuit—the RCD will sit idle while the cable overheats. That’s the MCB’s job. RCDs have one mission: detect current leaking to ground and trip before it kills someone.

ප්රෝ-ඉඟිය #1: If an RCD trips and won’t reset, don’t keep forcing it. Something is causing current to leak—a damaged appliance, moisture in a junction box, or deteriorated cable insulation. Find and fix the fault first. Bypassing or replacing the RCD without addressing the root cause is gambling with someone’s life.

How RCDs Work: The Life-Saving Detection System

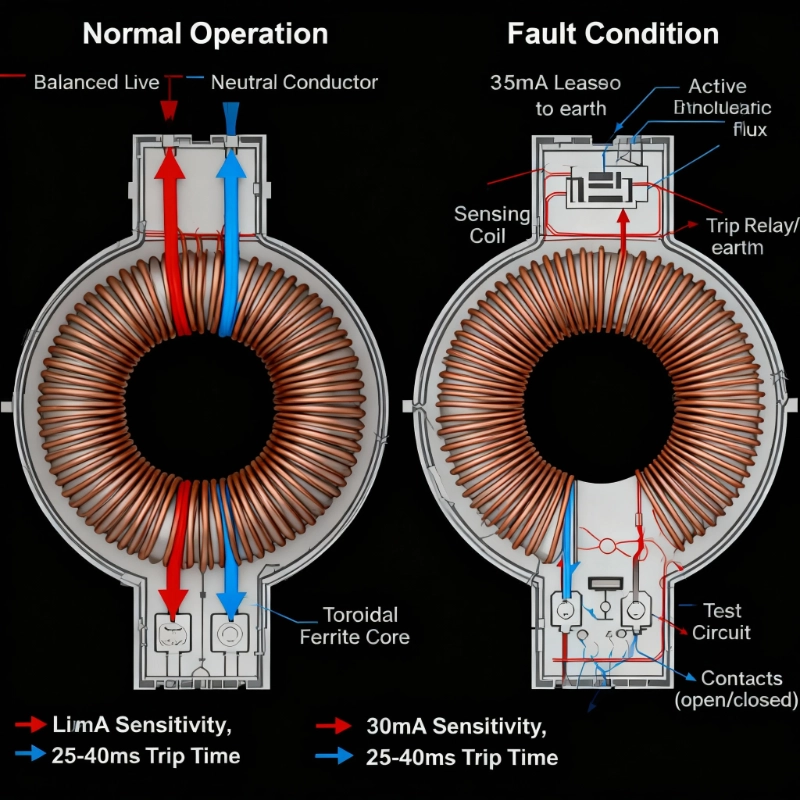

Inside every RCD sits a remarkably elegant device: a toroidal current transformer (also called a differential transformer). This transformer continuously compares the current in the live conductor against the current in the neutral conductor. Here’s how it works:

The Normal State (No Trip)

Both the live and neutral conductors pass through the center of a toroidal ferrite core. Under normal operation, 5A flows out through the live wire, and exactly 5A returns through the neutral wire. These two currents create magnetic fields in the toroidal core that are equal in magnitude but opposite in direction—they cancel each other out. No net magnetic flux exists in the core, so no voltage is induced in the sensing coil wrapped around the core. The RCD remains closed.

The Fault State (Trip)

Now a fault occurs: a person touches an exposed live part, or cable insulation breaks down, allowing 35 mA of current to leak to earth. Now 5.035A flows out through the live wire, but only 5.000A returns through the neutral wire. The missing 35 mA creates an imbalance—the magnetic fields no longer cancel. This imbalance induces a voltage in the sensing coil, which triggers the trip mechanism (usually a relay or solenoid), mechanically opening the contacts and disconnecting the circuit.

All of this happens in 25 to 40 milliseconds at rated residual current (IEC 61008-1 requires tripping within 300 ms at rated IΔn, and much faster at higher residual currents). For a 30 mA RCD, the device must trip when residual current reaches 30 mA, but typically trips somewhere between 15 mA (50% of rating) and 30 mA (100% of rating). At 150 mA (5× rating), the trip time drops to under 40 milliseconds.

The Test Button

Every RCD includes a test button that you should press quarterly. Pressing the test button creates an artificial imbalance by routing a small amount of current around the toroidal transformer, simulating a ground fault. If the RCD doesn’t trip when you press the test button, the device is faulty and must be replaced immediately. Testing is not optional—it’s the only way to verify the RCD will work when someone’s life depends on it.

What RCDs Cannot Detect

RCDs have blind spots. They cannot detect:

- Phase-to-phase faults: If someone touches both live and neutral simultaneously (or two phases in a three-phase system), current enters through one conductor and leaves through another—no imbalance, no trip.

- Overcurrent or short circuits: A dead short between live and neutral creates massive current flow, but if it’s balanced (same current out and back), the RCD sees nothing.

- Faults downstream of the RCD: If the fault occurs on the load side of the RCD but doesn’t involve earth, the RCD won’t help.

This is why you need MCBs. RCDs are specialists—they do one thing brilliantly, but they’re not a complete protection solution.

ප්රෝ-ඉඟිය #2: If you have multiple RCDs in a system and one keeps tripping, the fault is on a circuit protected by that specific RCD. Don’t swap RCDs around hoping the problem will disappear—trace the fault by isolating circuits one at a time until you find the offending load or cable.

RCD Types: Matching Device to Load

Not all RCDs are created equal. Modern electrical loads—especially those with power electronics—can produce residual currents that older RCD designs won’t detect reliably. IEC 60755 and the updated IEC 61008-1:2024 / IEC 61009-1:2024 standards define several RCD types based on the waveform they can detect:

Type AC: Sinusoidal AC Only

Type AC RCDs detect residual sinusoidal alternating current only—the traditional 50/60 Hz waveform. These were the original RCD design and work perfectly for resistive loads, simple appliances, and traditional AC motors.

Limitation: Type AC RCDs may fail to trip—or trip unreliably—when residual current contains DC components or high-frequency distortion. Many modern appliances (variable-frequency drives, EV chargers, induction cooktops, solar inverters, LED drivers) produce rectified or pulsating DC residual currents that Type AC devices cannot reliably detect.

Where it’s still acceptable: Lighting circuits with incandescent or basic fluorescent fixtures, simple resistive heating, circuits feeding only traditional AC appliances. But even here, Type A is becoming the safer default.

Type A: AC + Pulsating DC

Type A RCDs detect both sinusoidal AC residual current and pulsating DC residual current (half-wave or full-wave rectified). This makes them suitable for most modern residential and commercial loads, including single-phase variable-speed appliances, washing machines with electronic controls, and modern consumer electronics.

Why it matters: A clothes dryer with a VFD motor, a modern refrigerator with inverter compressor, or an induction cooktop can all produce pulsating DC residual currents under fault conditions. A Type AC RCD may not trip reliably. Type A RCDs are the minimum standard in many European jurisdictions as of 2020+.

ප්රෝ-ඉඟිය #3: If you’re specifying protection for any circuit with variable-speed drives, inverter appliances, or modern HVAC equipment, default to Type A as a minimum. Type AC is increasingly obsolete for anything beyond basic resistive loads.

Type F: Higher Frequency Protection

Type F RCDs (also called Type A+ or Type A with enhanced frequency response) detect everything Type A detects, plus higher-frequency residual currents and composite waveforms. They’re designed for loads with frequency converters and are specified in some European standards for circuits supplying equipment with power electronic front-ends.

Type B: Full DC and AC Spectrum

Type B RCDs detect sinusoidal AC, pulsating DC, and smooth DC residual currents up to 1 kHz. Smooth DC is the big differentiator—it’s produced by three-phase rectifiers, DC fast chargers, solar inverters, and some industrial drives.

Why Type B is critical for EVs: Electric vehicle chargers (especially DC fast chargers and AC chargers with Mode 3 control) can produce smooth DC fault currents that flow to ground through the protective earth. A Type A RCD will not detect these faults reliably. IEC 62955 defines Residual DC current Detecting Devices (RDC-DD) specifically for EV charging equipment, and many jurisdictions require Type B or RCD-DD protection for EV charging points.

When you must use Type B:

- EV charging equipment (unless an RCD-DD is installed at the EVSE)

- Solar photovoltaic installations with grid-tied inverters

- Industrial variable-frequency drives (three-phase rectifiers)

- Medical equipment with significant DC leakage potential

Type S (Selective / Time-Delayed)

Type S RCDs have an intentional time delay (typically 40-100 ms longer than standard RCDs) to provide selectivity in systems with multiple cascaded RCDs. Install a Type S RCD upstream (e.g., on the main incomer) and standard RCDs downstream on individual circuits. If a fault occurs on a branch circuit, the downstream RCD trips first, leaving other circuits energized.

RCD Type Selection Flowchart Summary

- Resistive loads only (rare) → Type AC acceptable, but Type A is safer

- Modern residential/commercial (appliances, electronics) → Type A minimum

- EV charging, solar PV, three-phase VFDs → Type B or RCD-DD

- Cascade protection (main incomer) → Type S

What Is an MCB (Miniature Circuit Breaker)?

අ කුඩා පරිපථ කඩනය (MCB) is an automatically operated electrical switch designed to protect electrical circuits from damage caused by overcurrent—either from prolonged overload or sudden short circuit. Governed by IEC 60898-1:2015+Amendment 1:2019 for household and similar installations, MCBs have largely replaced fuses in modern distribution boards worldwide because they’re resettable, faster, and more reliable.

What makes an MCB different from a simple on/off switch is its dual-protection mechanism: thermal protection for sustained overloads (120-200% of rated current over minutes) and magnetic protection for short circuits and severe faults (hundreds to thousands of percent over rated current, tripping in milliseconds).

Here’s what MCBs protect against:

- අධි බර: A circuit rated for 16A continuously carrying 20A. The cable insulation slowly heats beyond its rating, eventually failing and potentially starting a fire. The MCB’s thermal element detects this prolonged overcurrent and trips before insulation damage occurs.

- කෙටි පරිපථ: A fault creates a bolted connection between live and neutral (or live and earth), allowing fault current limited only by source impedance—potentially thousands of amps. The MCB’s magnetic element trips in 5-10 milliseconds, extinguishing the arc and preventing cable vaporization.

What MCBs do NOT protect against: Electric shock from earth leakage. A 30 mA current through a person’s body is more than enough to kill, but it’s nowhere near the threshold needed to trip even the most sensitive MCB.

ප්රෝ-ඉඟිය #4: Check your MCB ratings against your cable current-carrying capacity (CCC). The MCB should be rated at or below the cable’s CCC to ensure the MCB trips before the cable overheats.

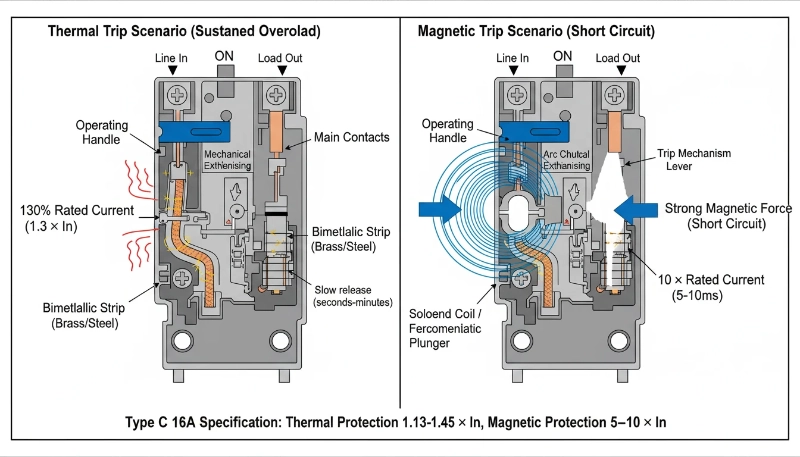

How MCBs Work: The Dual-Guardian System

Inside every MCB sit two independent protection mechanisms, each optimized for a different threat: The Thermal Guardian (bimetallic strip) for sustained overloads, and The Magnetic Sniper (solenoid coil) for instantaneous short-circuit faults.

The Thermal Guardian: Bimetallic Strip Protection

Imagine two different metals—typically brass and steel—bonded into a single strip. When current flows through this bimetallic element, resistive heating occurs. But here’s the clever part: the two metals expand at different rates. Brass expands faster than steel. As the strip heats, the differential expansion causes it to bend predictably in one direction.

When your circuit is carrying rated current (say, 16A on a C16 MCB), the bimetallic strip heats to equilibrium but doesn’t bend far enough to trip. Push the circuit to 130% of rated current (20.8A), and the strip begins bending noticeably. At 145% (23.2A), the strip bends enough to release a mechanical latch, opening the contacts and breaking the circuit.

The Magnetic Sniper: Instantaneous Electromagnetic Trip

For short circuits and severe faults, waiting even a few seconds is too slow. Fault current can vaporize copper and ignite nearby materials in under 100 milliseconds. Enter the magnetic trip—the MCB’s instantaneous protection.

Wrapped around a section of the MCB’s current path is a solenoid coil. Under normal current flow, the magnetic field generated by this coil isn’t strong enough to actuate anything. But when fault current hits—say, 160A on that same C16 MCB (10× rated current)—the magnetic field becomes powerful enough to yank a ferromagnetic plunger or armature, mechanically tripping the latch and opening the contacts.

This happens in 5-10 milliseconds. No heating required. No time delay. Just pure electromagnetic force proportional to current.

MCB Trip Curves: Understanding B, C, and D

Every electrical load has a steady-state operating current and an inrush current—the brief surge when the load first energizes. If you protect a motor circuit with the wrong MCB, the motor’s inrush will trigger the magnetic trip every time you start the motor. This is why IEC 60898-1 defines three trip curves:

Type B: Low Inrush (3-5× In)

Typical applications: Pure resistive loads (electric heaters, incandescent lighting), long cable runs where fault current is naturally limited by impedance.

When to avoid Type B: Any circuit with motors, transformers, or switch-mode power supplies.

Type C: General Purpose (5-10× In)

Typical applications: General lighting (including LED), heating and cooling equipment, residential and commercial power circuits, office equipment.

Default choice: If you’re unsure which type to specify and the application isn’t explicitly high-inrush, default to Type C. It handles 90% of applications.

Type D: High Inrush (10-20× In)

Typical applications: Direct-on-line motor starters, transformers, welding equipment.

When Type D is mandatory: Motors with high starting torque requirements or frequent start-stop duty cycles.

ප්රෝ-ඉඟිය #5: Wrong MCB curve selection is the #1 cause of nuisance tripping complaints. Match the curve to the load.

RCD vs MCB: The Core Differences

| විශේෂාංගය | ආර්සීඩී | MCB |

|---|---|---|

| ආරක්ෂා කරයි. | People (Shock) | Circuits & Equipment (Fire/Damage) |

| ක්රමය | Detects current imbalance (Leakage) | Detects current magnitude (Heat/Magnetic) |

| සංවේදීතාව | High (mA) | Low (Amps) |

| Blind Spot | අධි බර/කෙටි පරිපථය | පෘථිවි කාන්දුව |

When to Use RCD vs MCB: Application Guide

The question isn’t “RCD or MCB?”—it’s “where do I need RCD in addition to MCB?”

Scenarios Requiring RCD Protection (in addition to MCB)

- තෙත් සහ තෙත් ස්ථාන: Bathrooms, kitchens, laundry areas, outdoor outlets (NEC 210.8, BS 7671 Section 701).

- Socket Outlets: Outlets likely to supply portable equipment.

- TT Earthing Systems: Where earth fault loop impedance is too high for MCB alone.

- Specific Equipment: EV charging, Solar PV, Medical locations.

Scenarios Where MCB Alone Is Sufficient

- Fixed equipment in dry locations (inaccessible to ordinary persons).

- Lighting circuits in dry locations (depending on local code).

- Dedicated circuits for fixed loads like water heaters (non-wet areas).

Pro-Tip #6: When in doubt, add the RCD. The incremental cost is trivial compared to the cost of an electric shock injury.

Combining RCD and MCB for Complete Protection

Approach 1: Separate RCD + MCB

Install an RCD upstream (closer to the source) protecting a group of MCBs downstream.

- Advantage: Cost-effective.

- Disadvantage: If RCD trips, all downstream circuits lose power.

Approach 2: RCBO (Residual Current Breaker with Overcurrent Protection)

ඇන් ආර්සීබීඕ combines RCD and MCB functionality in a single device.

- Advantage: Independent protection per circuit. Better fault diagnosis.

- Disadvantage: Higher cost per circuit.

පොදු ස්ථාපන දෝෂ සහ ඒවා වළක්වා ගන්නේ කෙසේද

- Mistake #1: Using MCB Alone in Wet Locations. Fix: Install 30 mA RCD protection.

- Mistake #2: Wrong RCD Type for Modern Loads. Fix: Use Type A or Type B for variable-speed drives/EVs.

- Mistake #3: Shared Neutrals Across RCD-Protected Circuits. Fix: Ensure each RCD circuit has a dedicated neutral.

- Mistake #4: Oversized MCB for Cable Rating. Fix: Select MCB rating ≤ cable CCC.

- Mistake #5: Ignoring RCD Test Button. Fix: Test quarterly.

නිතර අසන ප්රශ්න

Can I replace an MCB with an RCD?

No. An MCB protects against overcurrent; an RCD protects against shock. You need both.

How often should I test my RCD?

Test every RCD at least quarterly (every 3 months) using the built-in test button.

Why does my RCD keep tripping?

Common causes include genuine ground faults, cumulative leakage from too many appliances, transient surges, or shared neutral wiring errors.

Standards & Sources Referenced

- IEC 61008-1:2024 (RCCBs)

- IEC 61009-1:2024 (RCBOs)

- IEC 60898-1:2015+A1:2019 (MCBs)

- IEC 62955:2018 (RDC-DD for EVs)

- NEC 2023 (NFPA 70)

- BS 7671:2018+A2:2022

Timeliness Statement: All technical specifications, standards, and safety data accurate as of November 2025.

Need help selecting the right protection devices for your application? VIOX Electric offers a complete range of IEC-compliant RCDs, MCBs, and RCBOs for residential, commercial, and industrial installations. Our technical team can assist with device selection, compliance verification, and application engineering. අපව අමතන්න for specifications and support.