Introduction: The Silent Guardian Against Electrical Surges

A facility manager in Texas arrived at her office building on a Monday morning in summer 2024 to find both rooftop HVAC units inoperative. The culprit: a utility transformer failure the night before had sent a power surge through the building’s electrical system. The repair assessment confirmed surge damage. The total cost? $43,620 to replace both units, plus $1,242 for temporary cooling while replacements were ordered—nearly $45,000 lost in a single transient event that lasted microseconds.

That’s the destructive power of an electrical surge. Your equipment doesn’t stand a chance against voltage spikes that can reach thousands of volts in fractions of a second. But here’s the critical point: a properly rated surge suppressor could have absorbed that transient energy and kept those HVAC systems running.

Surge suppressors—also called surge protectors or surge protective devices (SPDs)—are your first line of defense against electrical transients that damage or destroy sensitive equipment. They work by detecting dangerous voltage spikes and diverting surge energy away from connected loads before it can cause harm. Understanding how these devices accomplish this feat, and what their specifications really mean, helps you select protection that matches your equipment’s value and your facility’s risk exposure.

This guide explains surge suppressor technology from the inside out. We’ll break down the three core component technologies—metal oxide varistors (MOVs), gas discharge tubes (GDTs), and transient voltage suppressor (TVS) diodes—show you how each protects equipment during a surge event, decode the specifications you’ll see on product datasheets, and give you a practical framework for choosing the right suppressor for your application.

What Is a Surge Suppressor? Definition and Purpose

A surge suppressor is an electrical safety device designed to protect equipment from transient overvoltages—voltage spikes that exceed normal operating levels. Unlike a ķēdes pārtraucējs, which interrupts current when it exceeds a safe threshold for sustained periods, or a ground fault circuit interrupter (GFCI), which detects current leakage to ground, a surge suppressor addresses fast, short-duration voltage events that can damage or degrade sensitive electronics.

The surge suppressor sits between your power source and your equipment, continuously monitoring voltage. Under normal conditions (120 V AC in North America, for example), the suppressor remains electrically invisible—it presents high impedance and allows power to flow unimpeded to connected loads. The moment voltage rises above the suppressor’s activation threshold—its clamping voltage or breakdown voltage—the device transitions to a low-impedance state and shunts the excess energy to ground or dissipates it internally. This clamping action holds the voltage seen by your equipment to a safer level, typically in the range of 330 V to 500 V for residential 120 V circuits (per UL 1449 Voltage Protection Ratings). Once the transient passes, the suppressor returns to its high-impedance standby state, ready for the next event.

Understanding Electrical Surges: Sources and Risks

Electrical surges come from two broad categories: external events originating outside your facility and internal transients generated by equipment within your own electrical system.

External Surge Sources

Lightning is the most dramatic external source. A direct strike to a power line can inject currents exceeding 100,000 amperes and voltages reaching tens of thousands of volts. Even indirect lightning—a strike a mile away—couples energy into utility distribution lines through electromagnetic induction, sending kilovolt-level surges into homes and businesses.

Utility switching operations generate surges when the power company opens or closes circuit breakers, switches capacitor banks, or clears faults on the grid. These events produce voltage spikes typically in the 600 V to 1,000 V range—less severe than lightning but far more frequent.

Internal Surge Sources

Your own facility generates transients every day. Large three-phase motors, HVAC compressors, elevators, and industrial machinery produce back-EMF (electromotive force) voltage spikes when they start or stop. Switching power supplies, variable-frequency drives (VFDs), and power factor correction capacitors create oscillatory transients. These internal surges are typically lower in peak voltage than lightning but occur far more frequently—dozens or hundreds of times per day in industrial settings.

How Surge Suppressors Work: The Science Behind Protection

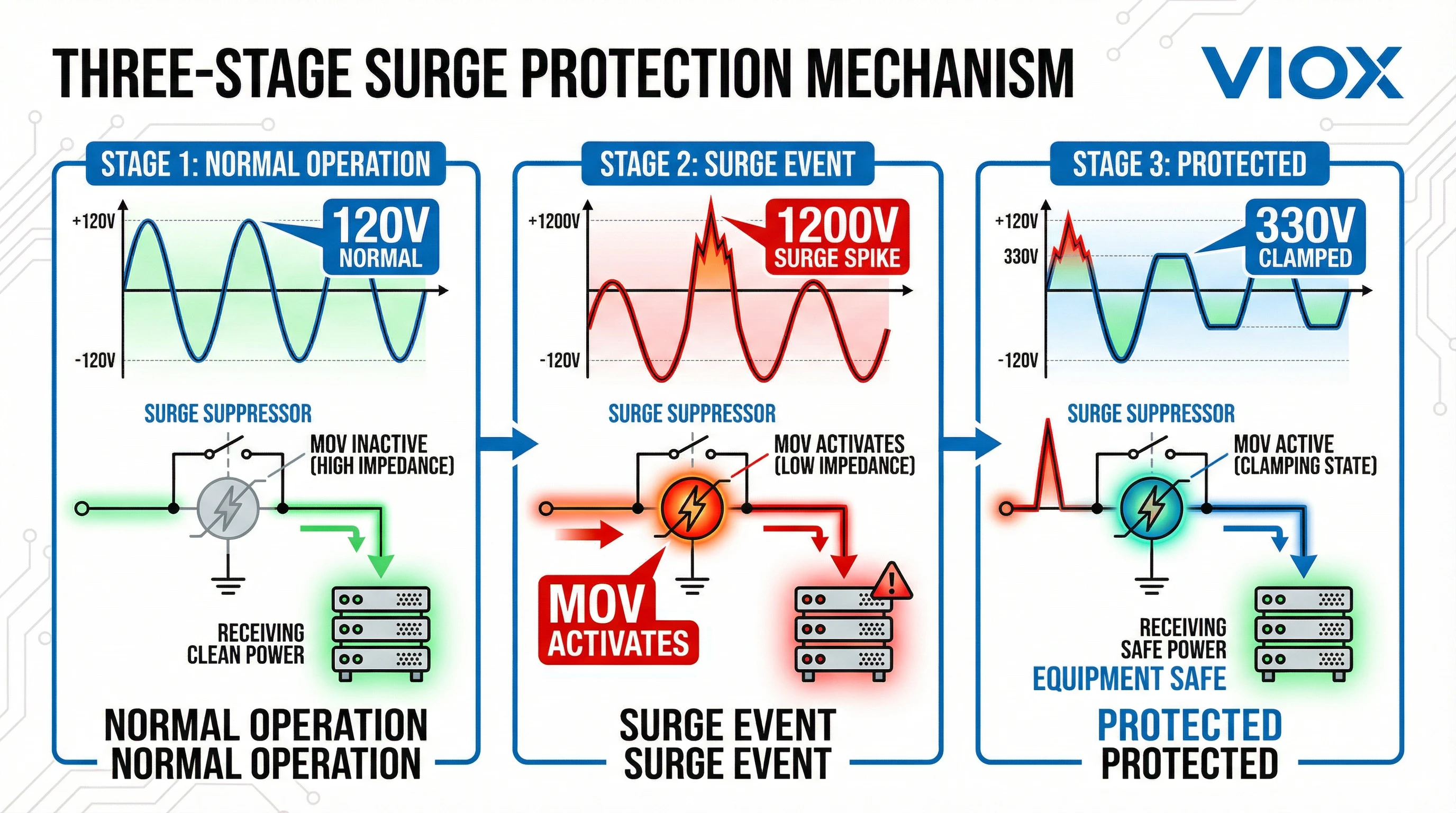

Surge suppressors function as voltage-activated switches or clamps. They remain in a high-impedance (non-conductive) state during normal operation, then rapidly transition to a low-impedance (conductive) state when voltage exceeds their activation threshold. This state change diverts surge current away from protected equipment or clamps the voltage to a safer level.

The Protection Sequence (Step-by-Step)

- Normal operation: Line voltage is 120 V AC. The surge suppressor presents extremely high resistance, drawing only microamperes of leakage current. Your equipment receives clean power.

- Surge event begins: A lightning strike or switching operation injects a transient. Voltage rises rapidly from 120 V to 1,000 V or higher within microseconds.

- Suppressor activates: When voltage crosses the component’s breakdown threshold, the device’s electrical properties change dramatically. Components like MOVs decrease resistance by orders of magnitude in nanoseconds.

- Energy diversion: Now in a low-impedance state, the suppressor creates a path to ground. Surge current flows through the suppressor instead of your equipment. The voltage is clamped to a safe level (e.g., 330 V).

- Atiestatīt: As the surge waveform decays, voltage drops back toward normal. The suppressor automatically returns to its high-impedance state, ready for the next event.

Key Components: MOV, GDT, and TVS Technologies

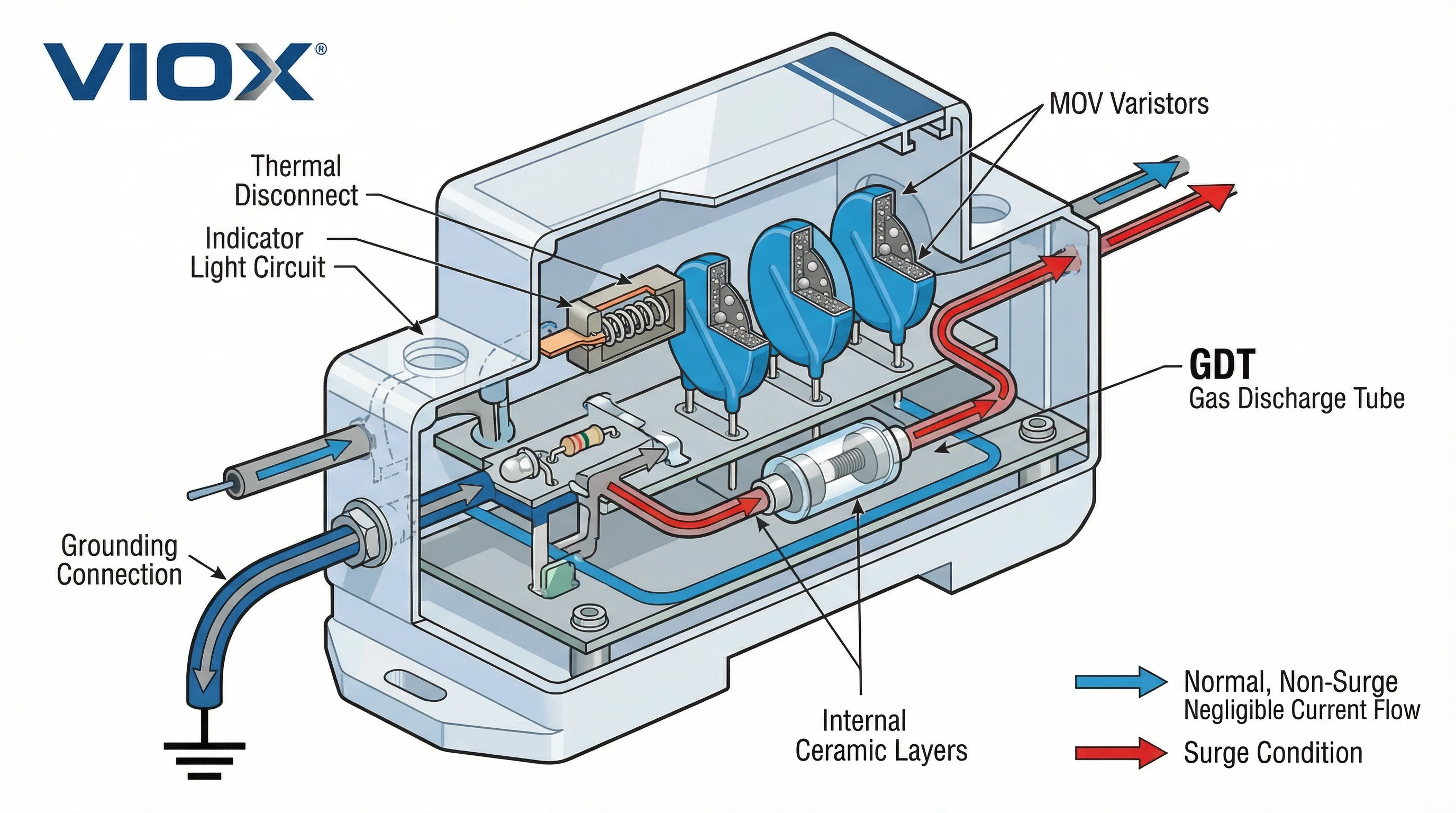

Surge suppressors rely on three core component technologies, each with distinct operating principles and performance characteristics.

Metal Oxide Varistor (MOV)

How it works: A voltage-dependent resistor made from sintered zinc oxide grains. Each grain boundary acts like a microscopic diode junction. At low voltages, it acts as an insulator; above its rated voltage, the junctions break down and resistance drops to milliohms.

Performance: Fast response (nanoseconds), high energy capacity (kilojoules), and moderate clamping voltage. MOVs degrade cumulatively with each surge event, which is why they are often paired with thermal fuses.

Pieteikums: The workhorse of surge protection. Found in power strips, whole-house SPDs, and industrial panels.

Gāzizlādes caurule (GDT)

How it works: A sealed tube filled with inert gas. Under normal voltage, it is an insulator. When voltage exceeds the sparkover threshold, the gas ionizes into a conductive plasma arc, creating a short circuit (crowbar action) that handles massive current.

Performance: Slower response (microseconds) but extremely high energy capacity (tens of kiloamperes). Excellent longevity but requires a “follow current” to be extinguished.

Pieteikums: Service entrances and telecom/datacom primary protection.

Transient Voltage Suppressor (TVS) Diode

How it works: A silicon avalanche diode. It operates in reverse bias and enters avalanche breakdown when voltage exceeds its limit, clamping voltage precisely.

Performance: Fastest response (picoseconds), very precise clamping, but lower energy capacity compared to MOVs or GDTs.

Pieteikums: Protecting sensitive electronics, data lines, and low-voltage DC circuits.

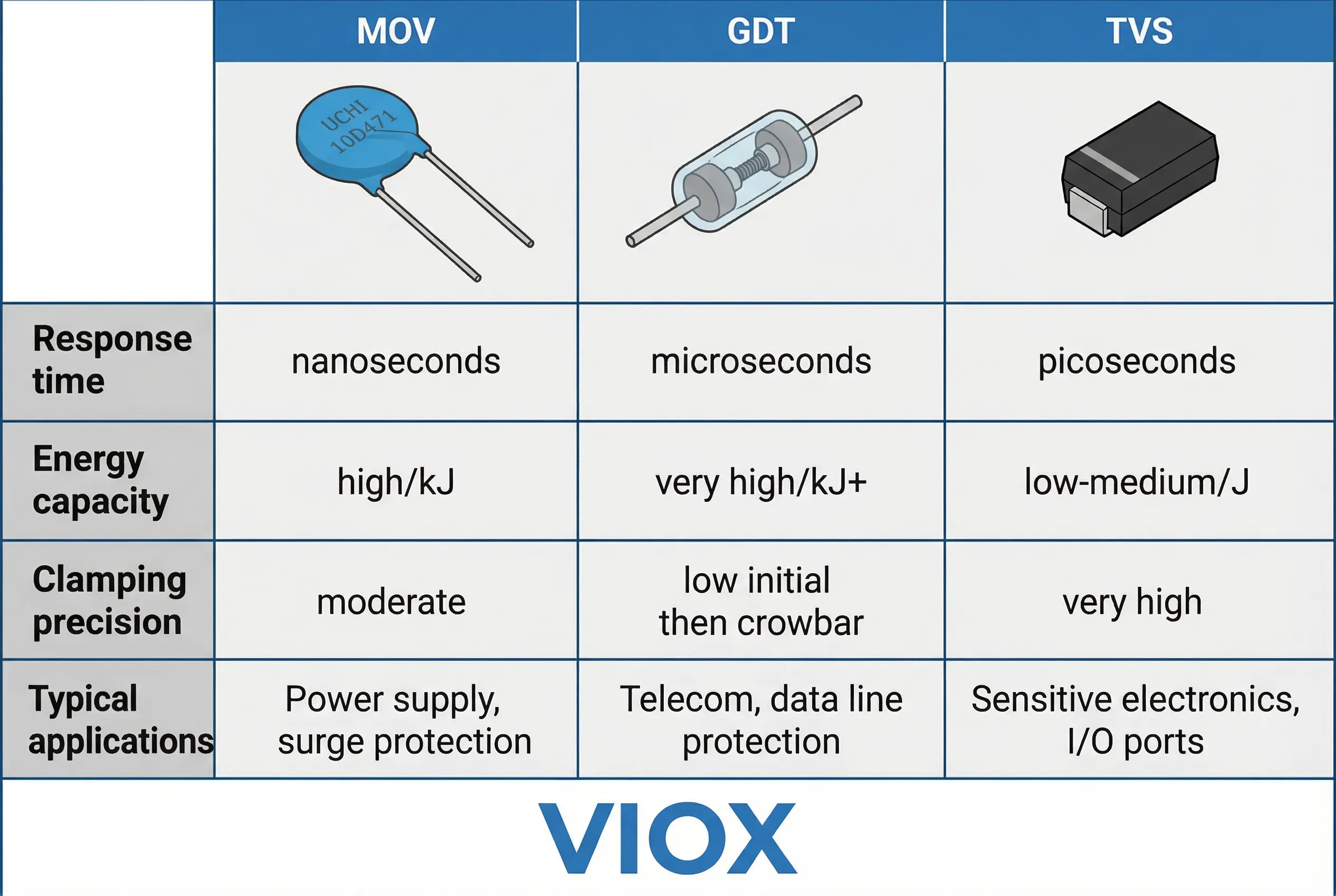

Technology Comparison Summary

| Tehnoloģija | Reakcijas laiks | Energy Capacity | Clamping Precision | Typical Application |

| MOV | Nanosekundes | High (kJ) | Mērens | General AC/DC surge protection |

| GDT | Mikrosekundes | Very High (kJ+) | Low initial, then crowbar | Service entrance, telecom primary |

| TVS diode | Picoseconds | Low-Medium (J) | Ļoti augsts | Data lines, DC circuits |

Protection Specifications Explained

Joules Rating (Energy Absorption): Indicates how much total energy the device can absorb before failure. Higher ratings generally mean longer service life. However, joules alone don’t indicate clamping performance.

Clamping Voltage / VPR: The maximum voltage the suppressor allows to pass through to your equipment. For 120V circuits, look for UL 1449 VPR ratings of 330V, 400V, or 500V. Lower is better for sensitive electronics.

Reakcijas laiks: How quickly the device reacts. While often marketed, standard MOVs (nanoseconds) are fast enough for almost all power-line surges. TVS diodes (picoseconds) are needed for data lines.

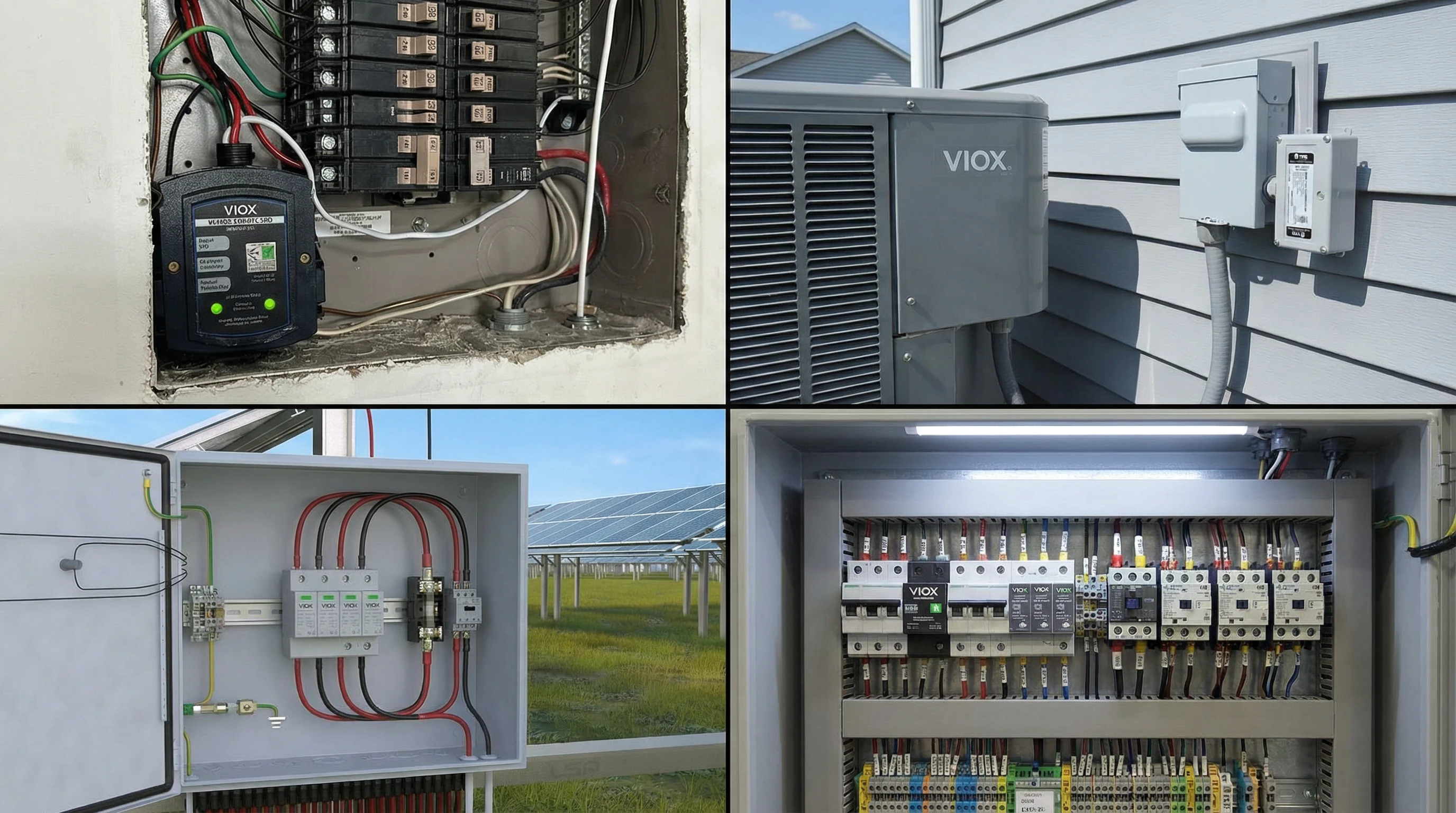

Types of Surge Suppressors: Whole-House vs Point-of-Use

Whole-House (Service Entrance) SPDs: Installed at the main panel. They protect the entire building from external surges (lightning, utility switching) before they enter the wiring. They handle high energy (20-50 kA) but have higher clamping voltages (600-1000V).

Point-of-Use SPDs: Power strips and plug-in units. They protect specific sensitive devices from residual voltage and internal surges. They offer tighter clamping (330-400V) but lower energy capacity.

Layered Protection Strategy: The best practice is to use both. A whole-house unit absorbs the bulk energy, while point-of-use units clean up the residual voltage for sensitive electronics.

When to Replace Your Surge Suppressor

- Indicator light shows failure: If the “Protected” LED is off or red, the MOVs are burned out. Replace immediately.

- After a major surge: Even if the light is on, a massive event (like a nearby lightning strike) can compromise the unit.

- Ik pēc 3–5 gadiem: In high-lightning areas, cumulative degradation from small surges wears out MOVs over time.

Selecting the Right Surge Suppressor

- Assess Equipment Value: High-value items (HVAC, Servers, Theater Systems) need better protection than a desk lamp.

- Match Location: Use Type 1 or Type 2 SPDs for service entrances/panels. Use Type 3 SPDs for point-of-use.

- Verify Standards: Look for UL 1449 or IEC 61643-11 certification.

- Check Indicators: Ensure the device has a visual or audible end-of-life indicator.

Conclusion: Investing in Equipment Protection

Surge suppressors offer an asymmetric return on investment: a modest cost for a whole-house SPD and quality power strips can protect tens of thousands of dollars in equipment and prevent costly downtime. Whether using MOVs, GDTs, or TVS diodes, the technology is proven and cost-effective. By understanding the specifications and employing a layered protection strategy, you can ensure your facility and home are resilient against the inevitable electrical transients of the modern grid.