You walk up to the AC disconnect or rooftop solar isolator you installed three years ago. The red handle is faded to a sickly pink. You turn it and CRACK—the handle crumbles in your hand like a dry biscuit.

Or worse, you open the casing and find the terminals covered in the fuzzy green corrosion of copper oxide. “But it was IP66 rated!” you protest. “It was sealed!”

Outdoors is a brutal test lab that exposes every shortcut in materials and installation. If your switches are dying young, it’s not bad luck. It’s usually one of three enemies:

The Sun, The Rain, or The Vandal.

This article walks through the physics and standards behind outdoor isolator failures—and what you should actually specify if you want an isolator to survive a decade instead of a couple of summers.

1. The Sun: The “Biscuit Effect” (ABS vs Polycarbonate)

Why cheap plastics turn to chalk

Many budget outdoor isolators are molded from general‑grade ABS (acrylonitrile–butadiene–styrene). Indoors, ABS is fine. Outdoors, under ultraviolet (UV) radiation, it starts to lose its backbone.

What happens:

- UV photons break the polymer chains in ABS, especially the butadiene phase, a process called photo‑oxidation.

- This leads to:

- Color fading and yellowing

- Surface micro‑cracking

- Loss of impact strength → the “biscuit” effect when you try to operate the handle

Typical durability numbers from plastics and enclosure manufacturers:

- Indoors (general ABS, away from direct sun): service life can be 15–25 years before impact strength drops significantly.

- Outdoors (un‑stabilized ABS in direct sun): UV and heat can reduce practical life to around 5–8 years—and in high‑UV regions, visible embrittlement can appear in as little as 2–3 years.

That matches what many electricians see: after a few hot summers, the ABS handle becomes powdery, and a firm twist is enough to snap it.

What UL 746C “f1” actually means

Plastics used in electrical equipment are tested under UL 746C – Polymeric Materials – Use in Electrical Equipment. Within that, the “f1” designation means:

- The plastic has been tested for UV exposureen

- Voor moisture and immersionen

- Is approved for outdoor use.

So if an isolator claims to be suitable for permanent outdoor installation, you should be asking:

“Is the housing material UL 746C f1‑rated for outdoor exposure?”

If the datasheet doesn’t say f1, you’re gambling with UV.

Why polycarbonate survives where ABS doesn’t

Polycarbonate (PC) is the workhorse for serious outdoor enclosures:

- Naturally tough and impact‑resistant

- Better UV stability than general‑grade ABS

- Often available in grades that are both UL 746C f1 en UL94 5VA flame‑rated

- Typical operating temperature range for PC enclosures: roughly ‑20°C to 120–140°C

Some key comparisons (typical, approximate values):

- ABS (general indoor grade)

- UV resistance: poor; most enclosure vendors say “indoor only” or “limited outdoor use”

- RTI (Relative Temperature Index): ~60°C (140°F)

- Outdoor rating: usually not f1

- Polycarbonate (outdoor grade)

- UV resistance: good; widely used for outdoor electrical housings, lighting covers, and meter boxes

- RTI: ~105°C (221°F)

- Often supplied as UL 746C f1 materials designed for long‑term outdoor use

In very high‑UV regions (e.g., New Zealand, Australia), enclosure manufacturers report ABS boxes degrading noticeably faster than polycarbonate in real installations—often needing replacement after only a few years in full sun, while PC boxes remain structurally sound.

The simple field “biscuit test”

You don’t need a lab:

- Find an old ABS AC isolator on a north‑ or west‑facing wall that’s been there 3–5 years.

- Press your thumb into the handle or lid.

- If it feels chalky or leaves a white smear, the surface is already degraded.

- Twist the handle with moderate force.

- If it snaps easily, the material has lost too much impact strength.

A UV‑stabilized polycarbonate isolator in the same conditions usually still feels tough and slightly flexible instead of crumbly.

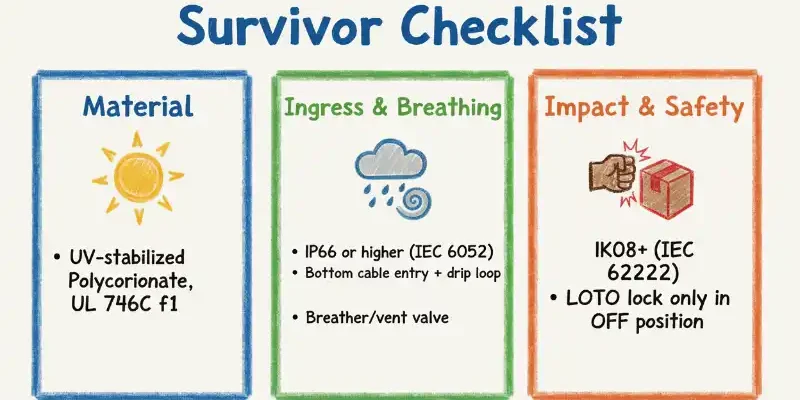

Survivor’s Choice for the Sun

When specifying an outdoor isolator:

- Housing material: UV‑stabilized polycarbonate, not generic ABS

- Plastics standard: UL 746C f1 (explicitly for outdoor use)

- Keywords to look for: “UV‑stabilized”, “UV‑resistant”, “outdoor‑rated, UL 746C f1”

- Rode vlag: “ABS enclosure, indoor/outdoor” with no UV or f1 data

2. The Rain: The “Vacuum Trap” (Why Top Entry Is a Bad Idea)

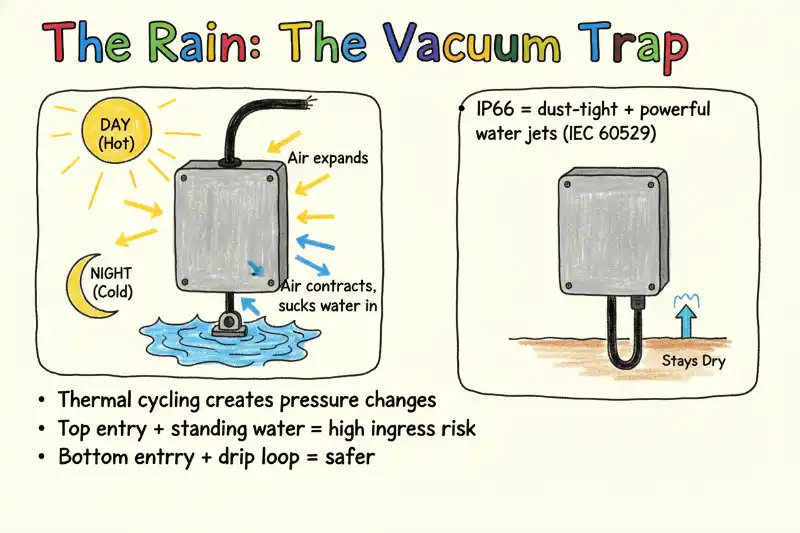

You bought an IP66 switch. You used reputable cable glands. Everything was tightened properly. Six months later, you open it and it’s full of water. “How can an IP66 box be full of water?”

What IP66 really guarantees (and what it doesn’t)

Volgens IEC 60529, the IP code defines protection against solids and liquids:

- IP66 means:

- 6 — “dust‑tight” (no ingress of dust)

- 6 — protected against powerful water jets from any direction

But:

- IP tests are short, static lab tests.

- They do not simulate years of thermal cycling, solar heating, cold rain, condensation.

Real‑world field reports show engineers documenting IP66/NEMA 4X enclosures ending up with condensation and standing water inside after months of service. A common pattern: hot sunny days, followed by rapid cooling (nightfall or cold rain) leads to internal pressure swings, which pulls moisture in past seals.

The physics: your isolator is a “lung”

An outdoor box breathes:

- Day – heating

- Sun heats the enclosure.

- Internal air temperature rises → pressure increases.

- Warm air escapes through microscopic gaps in seals, cable glands, and threads.

- Night – cooling

- Temperature drops (or cold rain cools the enclosure rapidly).

- Internal air contracts → pressure drops.

- The box tries to pull in air to equalize, creating a slight vacuum.

If you drilled your cable entry in the top of the box:

- Rainwater pools on the top surface and around the gland.

- When the box cools and a vacuum forms, it can literally suck liquid water past the threads or along the cable jacket.

- Repeat this for dozens or hundreds of cycles and you end up with condensation and eventually standing water.

IP66 is tested with spray, not with “top entry plus standing water plus daily pressure pulses.”

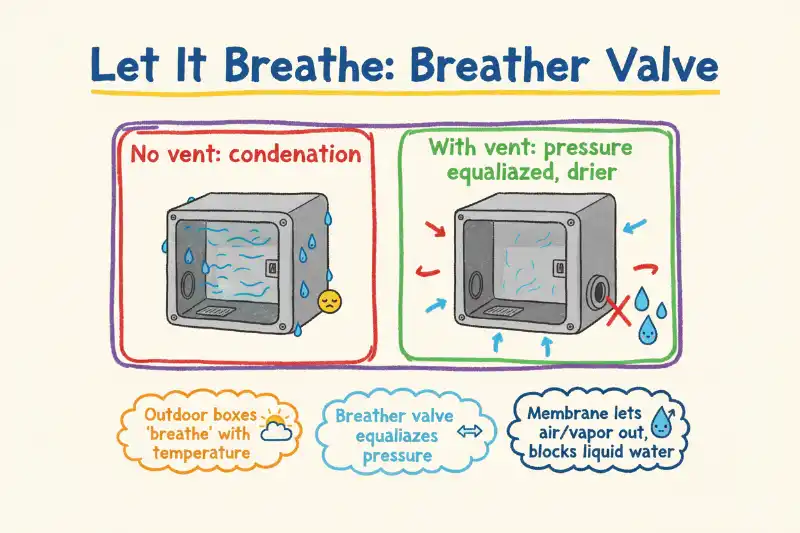

Why vent / breather elements work

Serious outdoor enclosures often include a vent / breather valve using a microporous membrane (commonly PTFE):

- The membrane allows air and water vapor to pass through.

- It blocks liquid water because the pores are small and surface tension keeps liquid out.

This provides two benefits:

- Pressure equalization: Minimizes the pressure gradient between inside and outside during heating/cooling cycles, reducing the tendency to pull water through imperfect seals.

- Moisture management: If some humidity does get in, the vent helps it dry out instead of trapping it as condensation.

Why bottom entry is non‑negotiable for reliability

Best‑practice recommendations from enclosure and junction box manufacturers:

- Bottom cable entry only

- Gravity keeps water away from the cable gland.

- Even driving rain is less likely to form a pond around the gland.

- Drip loop

- Route the cable downward then back upward into the gland.

- Water running along the cable falls off at the lowest point in the loop rather than entering the gland.

- Breather‑drain in larger/metal boxes

- Some Ex‑e and industrial boxes use a breather‑drain fitting to both equalize pressure and allow any accumulated water to escape.

Survivor’s Choice for the Rain

When picking and installing an outdoor isolator:

- Ingress protection: IP66 or higher, tested per IEC 60529

- Cable entry: always from the bottom, with a drip loop

- Ventilation: integrated air/breather valve or provision for a certified vent

- Expectation management:

- IP66 = dust‑tight + powerful water jet proof in a lab

- IP66 ≠ “immune to condensation” in the field without venting

If the product never mentions vents or breathing but makes big claims about being “completely sealed forever”, be skeptical.

3. The Vandal: Impact and LOTO (Don’t Lock It ON)

A common complaint: “Kids keep turning off my outdoor AC isolator as a prank. How do I stop them?” The dangerous temptation is to drill a hole and padlock the switch OP.

What LOTO is actually for

Lockout/Tagout (LOTO) is a safety practice defined in regulations like OSHA 29 CFR 1910.147 and similar rules worldwide. The core idea:

- Before working on equipment, you isolate the power en

- Lock the isolator in the OFF position so no one can re‑energize it accidentally.

Rotary isolators are designed with this in mind:

- The handle and cover usually have aligned lock holes only in the UIT position.

- That’s intentional: in an emergency or maintenance situation, you must be able to turn it OFF and lock it OFF.

If you modify the handle so it can be padlocked OP:

- Firefighters or maintenance technicians may not be able to de‑energize the circuit quickly in an emergency.

- You’ve effectively created a fire and shock hazard, and you’re outside the design intent and certifications of the device.

Why low‑impact boxes invite casual vandalism

A brittle or lightweight box mounted at foot height on a wall is an invitation:

- A casual kick, thrown rock, trolley bump, or ladder strike can crack cheap ABS or PVC housings.

- Once cracked:

- Water ingress risk skyrockets.

- Live parts may be exposed.

- The isolator may no longer operate safely.

This is why impact ratings matter, not just IP ratings.

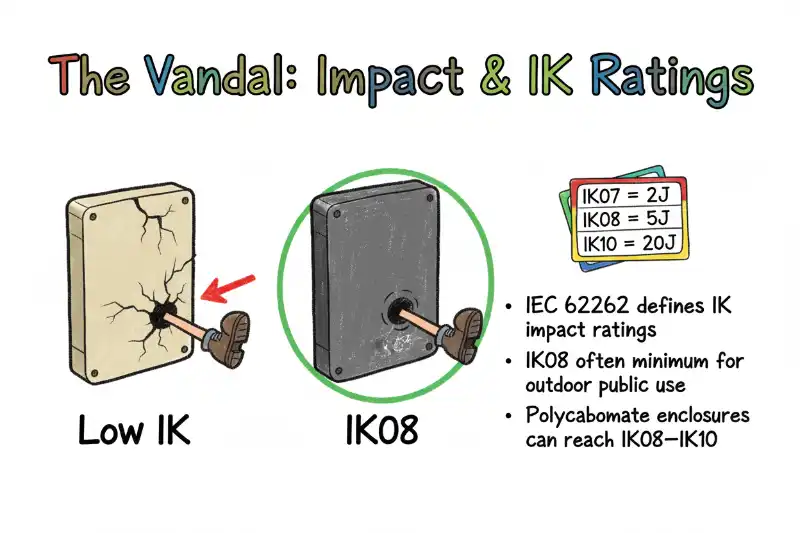

Understanding IK ratings (IK08, IK10, etc.)

Impact resistance for enclosures is defined in IEC 62262 as an IK code:

- The code indicates the energy of impact (in joules) that the enclosure can withstand.

Key levels:

- IK08 = 5 joules

- Equivalent to a 1.7 kg impactor dropped from 29.5 cm, or roughly a solid “boot kick” or hammer strike in many real‑world situations.

- IK09 = 10 J

- IK10 = 20 J (e.g. 5 kg mass dropped from 40 cm), common in high‑vandal public infrastructure.

Outdoor lighting, access control housings, public EV chargers, and junction boxes in exposed areas often target IK08–IK10.

Why polycarbonate wins again: impact‑resistant by design

Polycarbonate’s advantages for impact:

- Zeer hoog impact strength—often described as “virtually unbreakable” for practical purposes.

- Maintains toughness over a wide temperature range, rather than becoming brittle in the cold.

- Widely used in riot shields, protective covers for outdoor luminaires, and outdoor switchgear.

Because of this, many polycarbonate enclosures are certified to:

- IP66 / IP67 en

- IK08–IK10 per IEC 62262

ABS, especially after UV aging, is much more prone to shattering under similar impacts.

Survivor’s Choice for Vandals

For public or high‑traffic locations:

- Materiaal: polycarbonate (or GRP / metal) rather than general ABS

- Impact rating: at least IK08 per IEC 62262; consider IK10 in high‑risk areas

- LOTO usage:

- ONLY lock the isolator in the UIT position using factory‑provided lock holes

- Never DIY lock it OP

This keeps both your equipment and the people around it safer.

4. Standards That Actually Matter

When you read an isolator brochure, ignore the marketing adjectives (“heavy‑duty”, “industrial‑grade”) and look for standards and ratings.

Four standards worth caring about

- UL 746C – Polymeric Materials – Use in Electrical Equipment

- Zoek naar f1 rating for plastics used outdoors (UV + moisture tested).

- IEC 60529 – Degrees of Protection (IP Code)

- Defines IP ratings like IP66, IP67, IP68 for dust and water.

- IEC 62262 – IK Code

- Defines impact resistance (IK07, IK08, IK09, IK10).

- IK08 = 5 J, IK10 = 20 J.

- ASTM G154 – Standard Practice for UV Exposure of Nonmetallic Materials

- A common accelerated weathering protocol using fluorescent UV lamps.

- Used to compare and qualify plastics and coatings for outdoor durability by simulating years of sun in weeks/months.

If a product lists specific ratings against these standards, you’re dealing with data, not just adjectives.

5. Quick Comparison Tables

5.1 ABS vs Polycarbonate for Outdoor Enclosures

| Eigendom | ABS (general grade) | Polycarbonate (outdoor grade) |

|---|---|---|

| UV-bestendigheid | Poor; discolors and embrittles in sun | Good; widely used for long‑term outdoor exposure |

| UL 746C f1 (outdoor) | Gebruikelijk geen | Frequently ja, specifically formulated for outdoor |

| Relative Temperature Index | ~60°C (140°F) | ~105°C (221°F) |

| Impact strength (as new) | Good, but drops fast under UV | Very high, remains good after aging |

| Typical applications | Indoor housings, appliances, toys | Outdoor switchgear, lighting covers, solar combiner boxes |

| Kosten | Onder | Hoger |

| Suitable for long‑term outdoor? | Only with special UV‑stabilized grades and test data | Yes, when specified as UV‑stabilized / UL 746C f1 |

5.2 Common IP Ratings (IEC 60529)

| IP-classificatie | Dust Protection (1st digit) | Water Protection (2nd digit) | Typical usage |

|---|---|---|---|

| IP54 | Limited dust ingress | Splashing water | Light indoor/outdoor use |

| IP65 | Dust‑tight | Water jets | General outdoor enclosures |

| IP66 | Dust‑tight | Powerful water jets from any direction | Rooftop gear, exposed switchgear |

| IP67 | Dust‑tight | Temporary immersion (e.g. 1 m for 30 min, typical) | Equipment likely to be briefly submerged |

| IP68 | Dust‑tight | Extended / deeper immersion per manufacturer data | Underwater or buried equipment |

Remember: IP66 prevents water during tests, not automatically during years of thermal cycling.

5.3 IK Impact Ratings (IEC 62262)

| IK Code | Impact Energy (J) | Rough example | Typical application |

|---|---|---|---|

| IK05 | 0.7 J | Light knocks / small tool drops | Indoor fixtures |

| IK06 | 1 J | Moderate knocks | General housings |

| IK07 | 2 J | Heavier accidental knocks | Industrial interiors |

| IK08 | 5 J | Strong kick / hammer strike | Outdoor gear, public lighting, CCTV housings |

| IK09 | 10 J | Serious vandalism attempt | High‑risk industrial/public sites |

| IK10 | 20 J | Very severe impact / heavy tools | High‑vandal public areas, secure enclosures |

6. The “Survivor” Spec Sheet – Upgraded

If you want an outdoor isolator to last 10 years instead of 2, here’s what you should be checking:

1) Material & UV (Beating the Sun)

- Huisvesting: UV‑stabilized polycarbonate or equivalent outdoor‑rated plastic

- Plastics standard: UL 746C f1 (explicitly suitable for outdoor use)

- Gegevensblad: must mention UV resistance / weathering tests (ASTM G154 or similar)

2) Ingress & Breathing (Beating the Rain)

- Ingress protection: IP66 or higher (IEC 60529)

- Cable entry: from the bottom only, with a drip loop

- Vent: integrated breather / pressure‑equalizing valve or clear provision for one

- Realism: treat “completely sealed forever” claims with caution—unvented sealed boxes are the ones that most often fill with condensation.

3) Impact & Safe Lockout (Beating the Vandal)

- Slagvastheid: IK08 or higher (IEC 62262); consider IK10 for exposed public areas

- Materiaal: polycarbonate or metal; avoid brittle, unprotected ABS outdoors

- LOTO:

- Gebruik only the lock points designed by the manufacturer

- Lock UIT, never modify the device to lock OP

If a product—like your example “VIOX ELR Series” or any equivalent—can honestly claim:

- Polycarbonate housing, UL 746C f1

- IP66 / NEMA 4X

- IK08 or higher

- Integrated or supported air/breather valve

…then it’s not just a switch. It’s a small bunker for your electrical connections.

Don’t let the sun bake it, don’t let the vacuum drown it, and don’t let the vandals break it.